4B movement – Britannica

A Report on South Korea’s 4B Movement and its Implications for Sustainable Development Goals

The 4B movement in South Korea represents a significant feminist political stance and activist strategy. This report analyzes its origins, principles, and evolution, with a specific focus on its alignment with and challenges to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Core Tenets and Political Stance

The 4B movement is defined by a radical rejection of traditional patriarchal life scripts for women. Its name is derived from four Korean terms representing four refusals:

- Bihon: No marriage

- Bichulsan: No childbirth

- Biyonae: No dating (with men)

- Bisekseu: No sex (with men)

This framework is not a reflection of involuntary singlehood but a conscious political withdrawal from heteronormative institutions that participants view as inherently exploitative and unequal.

Direct Engagement with SDG 5: Gender Equality

The movement is a direct and radical attempt to achieve the objectives of SDG 5: Gender Equality. By refusing to participate in marriage and child-rearing, adherents protest the unequal burden of unpaid care and domestic work. They challenge the systemic gender-based violence and sexism prevalent in relationships, workplaces, and society at large, thereby demanding the elimination of all forms of violence against women and girls in the public and private spheres, a key target of SDG 5.

Historical Context and Catalysts for Change

The “Feminist Reboot” and Digital Activism

The 4B movement emerged from a “feminist reboot” in the mid-2010s, which saw activism shift from institutional academia to decentralized, online communities. Digital platforms became crucial for building solidarity and disseminating feminist knowledge among a younger generation disillusioned with the slow pace of institutional reform.

Key Incidents Fueling the Movement

Several high-profile events galvanized the movement, exposing what participants perceived as systemic misogyny and institutional failure:

- The 2016 Gangnam Station Femicide: The murder of a young woman by a man who targeted her because she was a woman sparked national outrage and highlighted the pervasive threat of gender-based violence.

- The “Pink Birth Map”: A 2016 government initiative mapping women of reproductive age was widely condemned for reducing women to their biological capacity, commodifying their bodies for state pronatalist goals.

- Digital Sex Crimes: The revelation of large-scale digital sex crime rings, such as the Nth Room case, underscored the dangers women face in digital spaces and the perceived inadequacy of law enforcement’s response.

Challenging Institutions for SDG 16: Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions

These events crystallized a belief that existing institutions were failing to provide safety and justice for women, a core tenet of SDG 16. The 4B movement’s withdrawal can be interpreted as a vote of no confidence in these institutions and a demand for accountable and inclusive systems that protect all citizens from violence and exploitation.

Impact on Social and Cultural Norms

Synergy with the “Escape the Corset” Movement

The 4B movement is closely linked to the “Escape the Corset” movement, which critiques oppressive feminine beauty standards. While “Escape the Corset” focuses on rejecting the physical and financial burdens of “decorative labor,” 4B extends this refusal to the interpersonal and institutional relationships that enforce gender hierarchy.

Advancing SDG 3 (Good Health) and SDG 8 (Decent Work)

Together, these movements advance multiple SDGs. By rejecting costly and often harmful beauty practices and the mental strain of conformity, they promote SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being. By refusing the economic burden of decorative labor and the expectation of unpaid domestic work, women seek greater economic autonomy, aligning with the principles of SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth.

Evolution and Community Building

Expansion to the 6B4T Framework

The movement has evolved into a broader framework known as 6B4T, adding principles of anti-consumerism and mutual support while rejecting cultural domains seen as reinforcing patriarchal norms.

- The “6B” adds: Bisobi (anti-consumerism) and Bidopbi (unmarried women helping each other).

- The “4T” adds: Tal-corset (escape the corset), Tal-jonggyo (escape religion), Tal-otaku (escape otaku culture), and Tal-idol (escape idol fandom culture).

From Online Solidarity to Offline Collectives

A significant outcome has been the formation of offline community collectives (e.g., WITH, EMIF, BecomeTrue). These groups provide practical support, from home repair workshops to social activities, creating alternative networks of solidarity.

Fostering SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities

These community-building efforts are a tangible contribution to SDG 11. By creating safe, supportive, and inclusive spaces, participants are building resilient local communities that function outside of traditional, patriarchal family structures, thereby enhancing the social sustainability of their environments.

Critiques and Global Perspectives

Internal and External Criticisms

The 4B movement faces criticism from conservative factions, who label it antisocial and selfish. More significantly, it has generated debate within feminist circles, particularly regarding its relationship with transgender and nonbinary individuals.

Challenges to SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities

Accusations of trans-exclusionary tendencies and biological essentialism within some factions of the movement present a challenge to the overarching goal of SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities. Critics argue that a truly inclusive feminist movement must advocate for the rights and safety of all marginalized gender identities, and that exclusionary rhetoric undermines broader solidarity.

International Reception

Following the 2024 U.S. presidential election, the 4B movement gained attention among some American women as a model for resistance against perceived rollbacks in gender equality and reproductive rights. This highlights its global resonance as a strategy of political refusal, though its direct applicability and the associated controversies remain subjects of international debate.

Analysis of Sustainable Development Goals in the Article

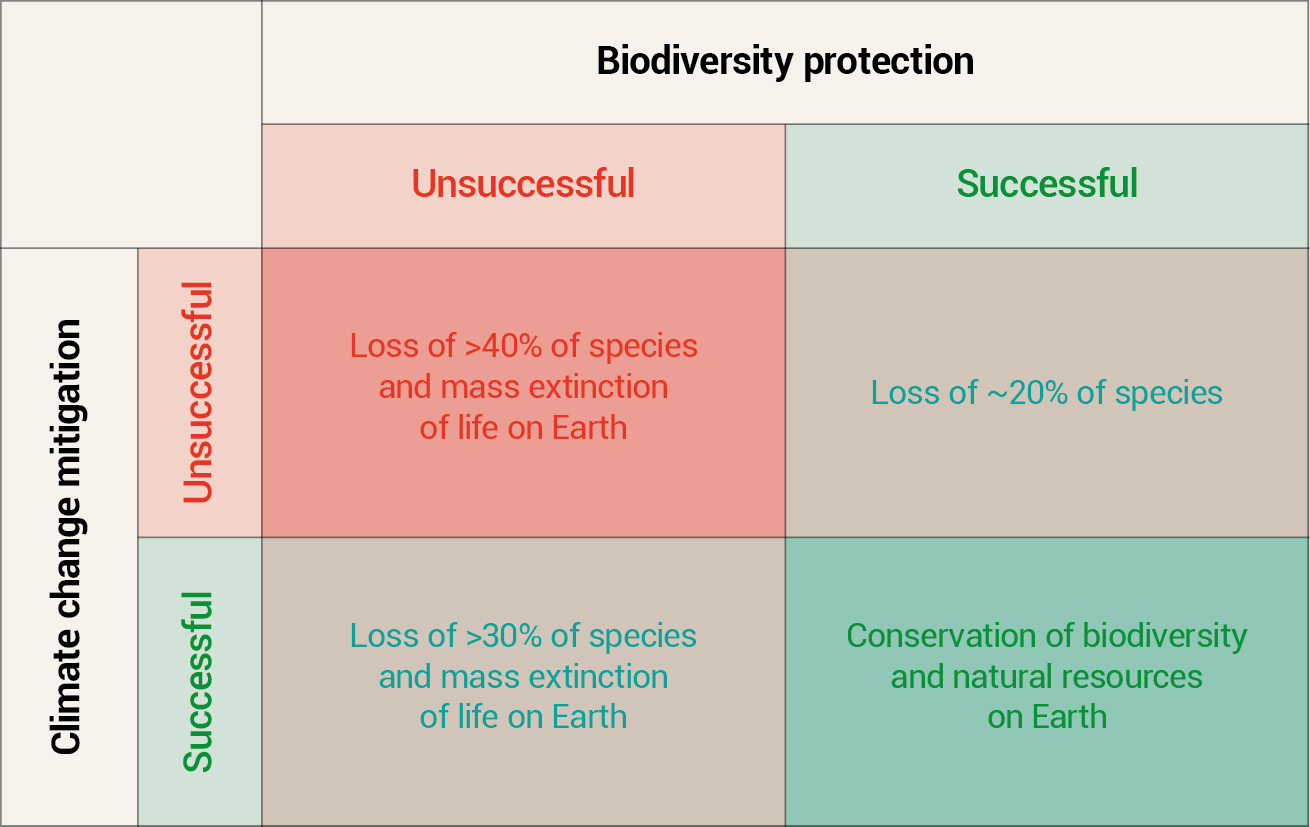

1. Which SDGs are addressed or connected to the issues highlighted in the article?

- SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being

- SDG 5: Gender Equality

- SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth

- SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities

- SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities

- SDG 16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions

2. What specific targets under those SDGs can be identified based on the article’s content?

-

SDG 5: Gender Equality

- Target 5.1: End all forms of discrimination against all women and girls everywhere.

The article describes the 4B movement as a radical rejection of the “heteronormative, patriarchal life script traditionally prescribed for women in South Korean society.” This script is a form of systemic discrimination that the movement aims to dismantle through individual and collective refusal. - Target 5.2: Eliminate all forms of violence against all women and girls in the public and private spheres, including trafficking and sexual and other types of exploitation.

The article explicitly cites numerous examples of violence against women that fueled the movement, including the “2016 Gangnam station femicide,” the “Nth Room case” involving sexual exploitation, and the “widespread nonconsensual recording of women through the use of hidden cameras in public restrooms and hotels.” - Target 5.4: Recognize and value unpaid care and domestic work… and the promotion of shared responsibility within the household and the family.

The movement’s core tenets of “no marriage” (bihon) and “no childbirth” (bichulsan) are a direct refusal to perform the unpaid domestic and reproductive labor traditionally and unequally expected of women within the patriarchal family structure. - Target 5.6: Ensure universal access to sexual and reproductive health and reproductive rights.

The article highlights the government’s “pink birth map,” which reduced women to their “biological capacity to bear children,” and the slogan “We refuse to be fertile, we refuse to be livestock.” This shows a direct conflict over women’s reproductive autonomy, which the 4B movement reclaims by refusing childbirth.

- Target 5.1: End all forms of discrimination against all women and girls everywhere.

-

SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being

- Target 3.7: Ensure universal access to sexual and reproductive health-care services… and the integration of reproductive health into national strategies and programmes.

The article discusses the state’s pronatalist policies and the backlash against them, indicating a struggle over reproductive health as a national strategy versus an individual right. The movement’s refusal of childbirth and sex with men is framed as a strategy for “emotional and physical survival,” which also relates to avoiding risks like “sexually transmitted infections.”

- Target 3.7: Ensure universal access to sexual and reproductive health-care services… and the integration of reproductive health into national strategies and programmes.

-

SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities

- Target 10.2: Empower and promote the social, economic and political inclusion of all, irrespective of… sex… or other status.

The 4B movement is an act of empowerment against the systemic social and political exclusion of women from a life of their own choosing. The article also notes internal critiques of the movement for its “exclusion of trans and nonbinary people,” directly engaging with the complexities of inclusion. - Target 10.3: Ensure equal opportunity and reduce inequalities of outcome, including by eliminating discriminatory… policies and practices.

The movement is a response to deep-seated inequalities of outcome for women, such as “workplace sexism,” “everyday violence,” and institutional bias in the justice system. It is a form of resistance against these discriminatory practices.

- Target 10.2: Empower and promote the social, economic and political inclusion of all, irrespective of… sex… or other status.

-

SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities

- Target 11.7: Provide universal access to safe, inclusive and accessible… public spaces, in particular for women.

The article details how the systemic danger women face in public spaces, such as “public restrooms and hotels and on public transportation” where hidden cameras are used, is a key factor driving the movement. The Gangnam station femicide in a public restroom is a stark example of the lack of safety for women.

- Target 11.7: Provide universal access to safe, inclusive and accessible… public spaces, in particular for women.

-

SDG 16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions

- Target 16.1: Significantly reduce all forms of violence and related death rates everywhere.

The “2016 Gangnam station femicide” is a direct example of lethal violence against women that the article identifies as a catalyst for the movement. - Target 16.3: Promote the rule of law… and ensure equal access to justice for all.

The article highlights a “persistent pattern of institutional bias” in law enforcement. It contrasts the “sluggish responses to egregious sex crimes committed by men” with the swift arrest of a woman in the Hyehwa station case, demonstrating a clear failure to provide equal access to justice.

- Target 16.1: Significantly reduce all forms of violence and related death rates everywhere.

3. Are there any indicators mentioned or implied in the article that can be used to measure progress towards the identified targets?

- Prevalence of violence against women: The article provides qualitative evidence through specific cases like the “Gangnam station femicide,” the “Nth Room case,” and “widespread nonconsensual recording of women.” These incidents serve as indicators of the high prevalence of physical, sexual, and digital violence against women.

- Birth rate / Fertility rate: The article mentions Korea’s “low birth rate” and the government’s concern over it. The 4B movement’s principle of “no childbirth” (bichulsan) reframes a declining birth rate not just as an economic issue but as a potential indicator of political protest and women’s assertion of reproductive autonomy.

- Marriage rates: The principle of “no marriage” (bihon) directly impacts marriage statistics. A decline in marriage rates among young women could be interpreted, in the context of this movement, as an indicator of resistance to patriarchal institutions.

- Public perception of safety: The article describes women’s fear of violence in public spaces like restrooms and on public transport. This implies that women’s perception of safety in their communities is a key indicator of progress towards Target 11.7.

- Trust in and fairness of the justice system: The article’s description of “institutional bias” and “sluggish responses” from law enforcement implies that the number of crimes reported by women and the disparity in investigation and conviction rates for crimes against women versus men are critical indicators of access to justice.

4. Table of SDGs, Targets, and Indicators

| SDGs | Targets | Indicators (Identified in the Article) |

|---|---|---|

| SDG 5: Gender Equality |

5.1: End all forms of discrimination.

5.2: Eliminate all forms of violence against women. 5.4: Recognize and value unpaid care and domestic work. 5.6: Ensure universal access to sexual and reproductive rights. |

Existence of a “patriarchal life script” as a form of discrimination.

Reported incidents of femicide (Gangnam station), digital sex crimes (Nth Room), and nonconsensual photography. Refusal of marriage and childbirth as a rejection of unpaid labor. Women’s refusal to be “fertile livestock” in response to state pronatalist policies like the “pink birth map.” |

| SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being | 3.7: Ensure universal access to sexual and reproductive health-care services. | Conflict between state pronatalist strategies and women’s demand for reproductive autonomy; fear of sexually transmitted infections as a reason for refusal. |

| SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities |

10.2: Empower and promote social inclusion.

10.3: Ensure equal opportunity and reduce inequalities of outcome. |

The movement as an act of empowerment; critique of the movement’s exclusion of trans and nonbinary people.

Existence of “workplace sexism” and systemic violence as inequalities of outcome. |

| SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities | 11.7: Provide universal access to safe and inclusive public spaces. | Systemic danger for women in public spaces (restrooms, public transport) due to violence and hidden cameras. |

| SDG 16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions |

16.1: Reduce all forms of violence.

16.3: Ensure equal access to justice for all. |

The occurrence of the “Gangnam station femicide.”

“Sluggish” law enforcement response to crimes against women and “institutional bias” in the justice system. |

Source: britannica.com

What is Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0

_1.png?#)