A ‘tropical’ disease is spreading in American wildlife – statnews.com

Report on the Emergence of Chagas Disease in the United States and its Implications for Sustainable Development Goals

Introduction and Key Findings

Recent research reveals a significant and previously underestimated public health threat within the United States: the silent spread of Chagas disease, caused by the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi. A study in Illinois found that over half of the sampled raccoon population was infected, indicating that the parasite is actively circulating in U.S. wildlife. This situation presents a direct challenge to achieving several Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly those related to health, sustainable communities, and environmental protection. The disease, long considered a “neglected tropical disease” confined to Latin America, is now endemic in parts of the U.S., with evidence of local transmission and a general lack of preparedness within the public health system.

Impact on SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being

The proliferation of Chagas disease directly undermines SDG 3, which aims to ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all. The disease poses a severe long-term health risk, often remaining asymptomatic for years before manifesting in severe and irreversible conditions. This directly contravenes SDG Target 3.3, which calls for an end to the epidemics of neglected tropical diseases.

- Health Consequences: Chronic infection can lead to life-threatening conditions such as heart failure, stroke, arrhythmias, and sudden death.

- Underdiagnosis and Lack of Awareness: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that approximately 300,000 people in the U.S. are infected, yet most are unaware. The medical community largely overlooks Chagas disease in differential diagnoses, creating a critical barrier to early detection and treatment.

- Treatment Gaps: While antiparasitic treatments are effective if administered early, the lack of routine testing and awareness means most opportunities for intervention are missed, allowing the disease to progress to an incurable stage.

Environmental Drivers: A Challenge to SDGs 11, 13, and 15

The spread of T. cruzi is intrinsically linked to environmental factors, highlighting the interconnectedness of human health and the planet’s well-being as outlined in several SDGs.

SDG 15: Life on Land

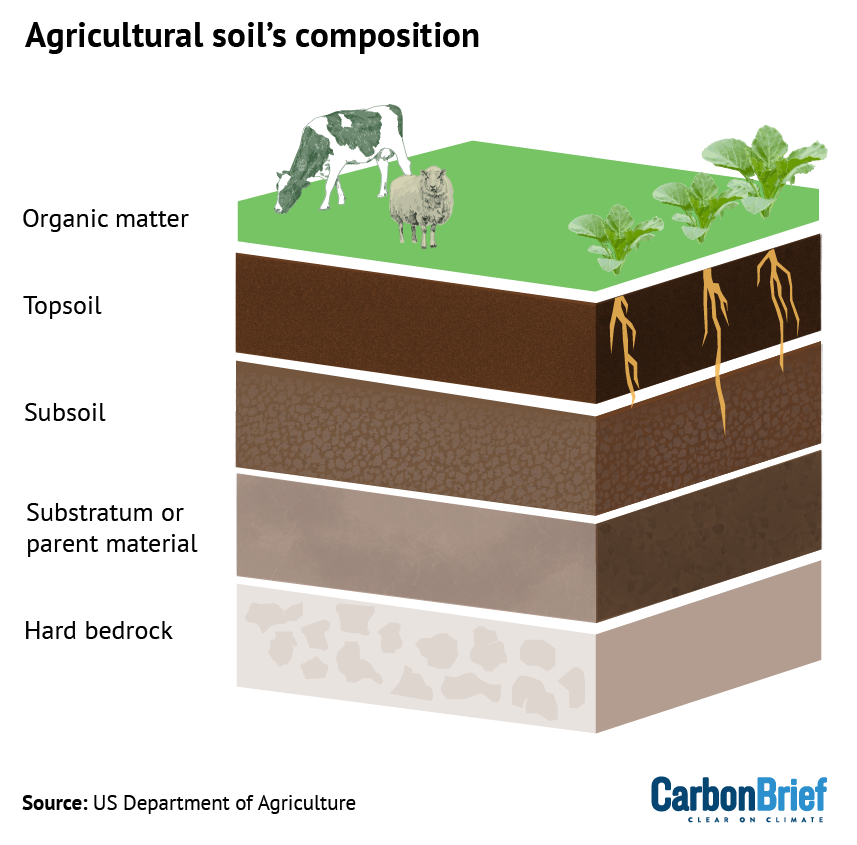

Chagas is a zoonotic disease, transmitted from wildlife to humans. The high prevalence in animals like raccoons and opossums across states including Texas, California, Louisiana, and the Midwest demonstrates a breakdown in the barrier between wildlife and human habitats. Land development and ecosystem disruption increase the likelihood of human-vector contact, creating conditions for disease spillover and challenging the sustainable management of terrestrial ecosystems.

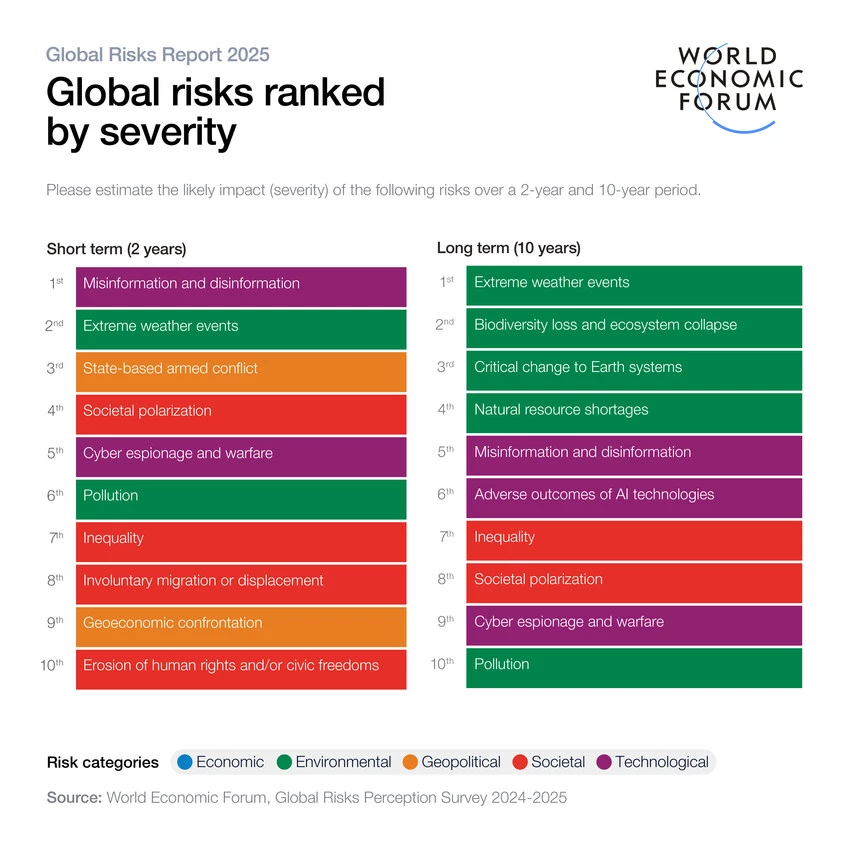

SDG 13: Climate Action

Climate change is identified as a key driver expanding the geographic range of the disease vector, the triatomine insect (or “kissing bug”). Rising temperatures allow these insects to thrive in new regions, increasing the at-risk population and underscoring the need to strengthen resilience to climate-related health hazards as mandated by SDG 13.

SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities

The risk of transmission is elevated in areas where human dwellings border natural landscapes. Features common in suburban and rural areas, such as dog shelters, poultry sheds, and woodpiles, provide ideal habitats for infected kissing bugs. This makes communities, particularly those at the rural-urban interface, more vulnerable and less resilient to this emerging health threat, conflicting with the goals of SDG 11.

Systemic Deficiencies and the Threat to SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities

The current response to Chagas disease in the U.S. is hampered by significant systemic failures. The misconception that it is solely an “imported” disease affecting immigrants can lead to diagnostic biases and health disparities, undermining SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities). Rural populations, agricultural workers, and outdoor enthusiasts are also at unacknowledged risk.

- Lack of standardized national surveillance for the disease.

- Absence of routine screening and diagnostic protocols in clinical practice.

- Low awareness among both the public and healthcare providers.

- Infections are primarily discovered incidentally, often too late for effective treatment.

Recommendations for a Coordinated Response Aligned with SDGs

Addressing the threat of Chagas disease requires a proactive and integrated approach grounded in the principles of sustainable development. The following actions are necessary to protect public health and make progress on the SDGs:

- Enhance Awareness and Education: Launch targeted awareness campaigns for clinicians and the public to correct misconceptions and highlight the risks of local transmission, a critical step for achieving SDG 3.

- Expand Diagnostic Access: Implement widespread and accessible diagnostic testing, especially in high-risk regions and for populations with unexplained cardiac issues, ensuring equitable access to healthcare as per SDG 10.

- Establish Robust Surveillance Systems: Develop and implement standardized national surveillance for human cases, vectors, and wildlife reservoirs to monitor the disease’s spread and inform public health interventions, supporting both SDG 3 and SDG 15.

- Promote Integrated Environmental Management: Incorporate public health risks like Chagas disease into land-use planning and climate adaptation strategies to build more resilient communities, in line with SDGs 11 and 13.

Which SDGs are addressed or connected to the issues highlighted in the article?

-

SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being

This is the most prominent SDG in the article. The entire text focuses on Chagas disease, a “neglected tropical disease,” its severe health consequences like “heart failure, stroke, arrhythmias, or sudden death,” the lack of diagnosis and treatment, and the need for a public health response. The article calls for improved awareness, diagnostics, and surveillance to protect human health.

-

SDG 13: Climate Action

The article directly links the spread of Chagas disease to climate change. It states that “triatomine bugs expand their geographic range due to climate change and environmental shifts,” which increases the risk of human exposure. This highlights the health impacts of climate change, a core concern of SDG 13.

-

SDG 15: Life on Land

The article establishes a clear link between the disease, wildlife, and ecosystems. It notes that the parasite is “spreading silently in wildlife” like raccoons and that the risk increases as “land development reshape ecosystems.” The discussion of disease spillover from wildlife to humans due to “complex relationships between humans, wildlife, and environmental change” directly relates to the sustainable management of terrestrial ecosystems.

What specific targets under those SDGs can be identified based on the article’s content?

-

Target 3.3: End the epidemics of neglected tropical diseases

The article explicitly identifies Chagas disease as a “neglected tropical disease” and warns of it becoming an “emerging public health crisis.” The call to “stop underestimating Chagas disease and start treating it like the threat it truly is” directly aligns with the goal of ending the epidemic of such diseases.

-

Target 3.d: Strengthen the capacity for early warning, risk reduction and management of national and global health risks

The article heavily criticizes the current lack of preparedness in the U.S., stating, “What’s worse is how unprepared we are.” It points out the absence of “standardized national surveillance” and a “knowledge gap” in the clinical community. The proposed solutions, including “Awareness campaigns,” “Expanded diagnostic access,” and “Continued wildlife surveillance,” are all measures to strengthen the capacity for early warning and risk management of a national health threat.

-

Target 13.1: Strengthen resilience and adaptive capacity to climate-related hazards

The article identifies the expansion of the disease vector’s habitat due to “climate change” as a key driver of increased risk. By calling for monitoring and preparation for this climate-driven health hazard, the article advocates for building resilience and adaptive capacity to the health consequences of climate change.

-

Target 15.5: Take urgent action to reduce the degradation of natural habitats

The article implies that human activities are increasing the risk of disease transmission. It mentions that “land development reshape ecosystems” and that the risk of human contact with infected bugs increases where “homes border wooded landscapes.” This points to the connection between habitat alteration, human-wildlife contact, and disease spillover, which this target aims to address.

Are there any indicators mentioned or implied in the article that can be used to measure progress towards the identified targets?

-

Incidence and prevalence of Chagas disease

The article provides several statistics that serve as baseline indicators for Target 3.3. These include the CDC’s estimate of “around 300,000 people living in the United States are infected,” the finding of “about 90 confirmed or suspected locally acquired Chagas cases in the U.S. between 2000 and 2020,” and a 2022 study estimating “about 10,000 locally acquired cases.” Tracking these numbers would measure progress in combating the disease.

-

Prevalence of the parasite in wildlife and vector populations

The article mentions specific research findings that can be used as indicators for surveillance (Target 3.d). These include: “More than half of the raccoons I sampled were infected with Trypanosoma cruzi,” and a Florida study revealing that “nearly 35% of triatomine bugs collected inside homes tested positive for T. cruzi.” Continued monitoring of these prevalence rates in animal and insect populations would indicate the level of underlying risk.

-

Rate of human-vector contact

An indicator for risk exposure is directly mentioned in the article’s reference to a Florida field study, which found that “23% [of triatomine bugs] had fed on humans.” This metric confirms “direct human-vector contact” and can be used to assess the immediate risk of transmission in specific areas.

-

Existence of a national surveillance system

The article implies an indicator for Target 3.d by stating, “There’s no standardized national surveillance.” The establishment of such a system would be a key milestone and a qualitative indicator of improved national capacity to manage this health risk.

Table of SDGs, Targets, and Indicators

| SDGs | Targets | Indicators |

|---|---|---|

| SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being | 3.3: End the epidemics of neglected tropical diseases. |

|

| SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being | 3.d: Strengthen the capacity for early warning, risk reduction and management of national and global health risks. |

|

| SDG 13: Climate Action | 13.1: Strengthen resilience and adaptive capacity to climate-related hazards. |

|

| SDG 15: Life on Land | 15.5: Take urgent action to reduce the degradation of natural habitats. |

|

Source: statnews.com

What is Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0

;Resize=805#)