Food banks have long prevented emissions. Now they’re getting into the carbon credit business. – Grist.org

Report on Food Bank Operations, Carbon Markets, and Contributions to Sustainable Development Goals

Introduction: The Intersection of Food Security, Waste Reduction, and Climate Action

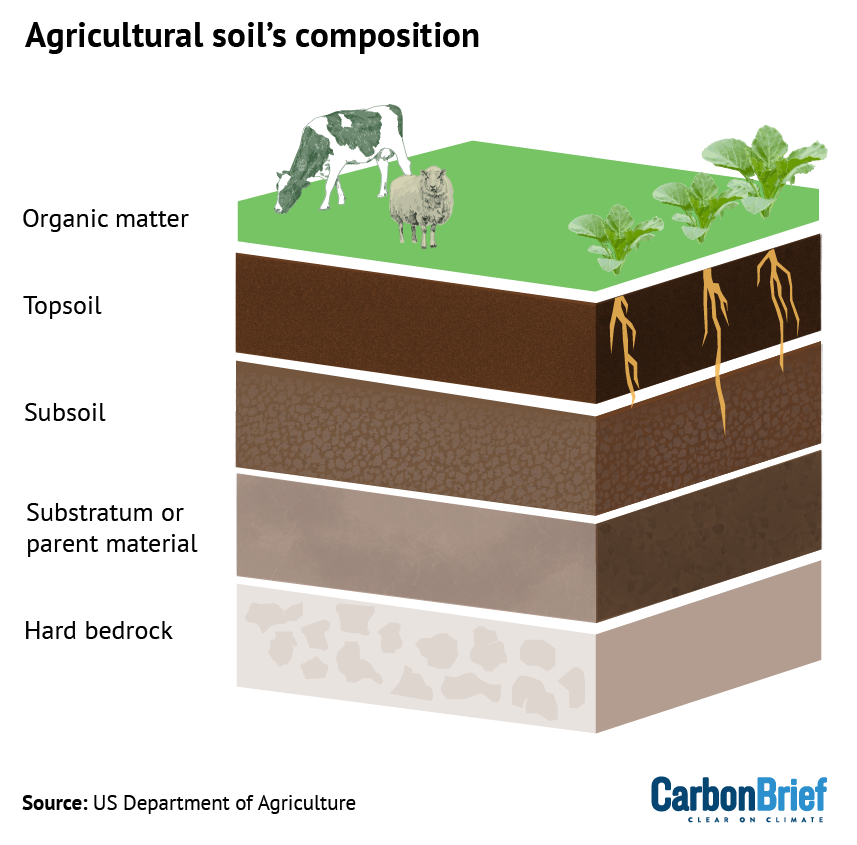

Food waste represents a significant challenge to global sustainability efforts, accounting for an estimated 8 to 10 percent of total greenhouse gas emissions. The decomposition of organic waste in landfills releases methane, a potent greenhouse gas, directly undermining progress on SDG 13 (Climate Action). Food banks serve a critical function at the intersection of several Sustainable Development Goals by rescuing surplus food. This activity simultaneously addresses SDG 2 (Zero Hunger) by providing nutrition to vulnerable populations and advances SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production) by preventing food waste. A recent initiative by the Global FoodBanking Network (GFN) seeks to quantify the climate benefits of these operations and leverage them to generate funding through the voluntary carbon market, creating a novel but controversial financing model.

Food Banks’ Role in Advancing the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development

Addressing SDG 2 (Zero Hunger) and SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production)

The primary mission of food banks is to combat food insecurity, directly contributing to the achievement of SDG 2. By redistributing unsold but edible food from retailers to individuals and families in need, they provide a vital social safety net. This process is intrinsically linked to SDG 12, specifically Target 12.3, which aims to halve per capita global food waste at the retail and consumer levels. The core operational model of a food bank involves:

- Rescuing surplus food from farms, grocers, and retailers.

- Preventing this food from entering the waste stream.

- Redistributing it to communities, thereby ensuring resources are consumed responsibly.

Contributions to SDG 13 (Climate Action)

By diverting organic matter from landfills, food banks prevent the anaerobic decomposition that produces methane. This constitutes a direct contribution to climate change mitigation efforts under SDG 13. The GFN’s Food Recovery to Avoid Methane Emissions (FRAME) methodology was developed to measure and verify these avoided emissions, translating the environmental impact of food banking into a quantifiable metric.

The Carbon Credit Initiative: A Model for Sustainable Financing

Program Overview and Alignment with SDG 17 (Partnerships for the Goals)

The GFN has initiated a program to enable member food banks to sell carbon credits based on their quantified emissions avoidance. This initiative, piloted in Mexico and Ecuador and expanding to 12 other countries, exemplifies SDG 17 (Partnerships for the Goals) by creating a financing mechanism that links non-profit social enterprises with the private sector. The program is a strategic response to funding instability, as traditional sources like foreign aid from wealthier nations are becoming less reliable. This new model seeks to create a self-sustaining revenue stream to enhance and expand food rescue operations.

Challenges and Criticisms of Carbon Market Engagement

Systemic Issues in Voluntary Carbon Markets

The engagement of non-profits in carbon markets is fraught with challenges. These markets have faced significant criticism for issues that could undermine the integrity of the food banks’ climate claims. Key problems include:

- Rampant Fraud and Greenwashing: Carbon credits can allow major polluters to claim carbon neutrality without making fundamental changes to their operations, a practice often labeled as greenwashing.

- Lack of Rigor: Analyses have shown many credits to be ineffective due to poor standards for monitoring, reporting, and verification.

- The “Additionality” Problem: A core principle of carbon offsetting is that the credit must fund an emissions reduction that would not have occurred otherwise. Proving this “additionality” has been a persistent challenge for many projects.

Specific Concerns Regarding the FRAME Methodology

While GFN has sought to create a rigorous methodology pending certification by the Gold Standard, experts have raised specific concerns regarding its framework. These critiques challenge whether the resulting credits represent legitimate and permanent emissions reductions.

- Baseline Assumptions: The methodology assumes that without the food bank’s intervention, all rescued food would have ended up in a landfill. This ignores other potential outcomes, such as the retailer selling the food at a discount.

- Demonstrating Additionality: Since food banks have long been engaged in food rescue, it is difficult to argue that the activity is entirely “additional.” GFN contends that revenue from credits will fund the expansion of their capacity, thereby enabling additional food rescue that would not otherwise be possible.

- Validity of Avoided Emissions vs. Carbon Removal: Some critics argue that only credits representing the physical removal and permanent storage of carbon (e.g., through biochar) should be considered legitimate offsets, as opposed to those based on avoided emissions.

Strategic Value and Future Outlook

Benefits Beyond Revenue Generation

Despite the controversies surrounding carbon markets, the process of quantifying environmental impact has yielded significant benefits for participating food banks. These outcomes support broader national and global sustainability efforts.

- Enhanced Data and Awareness: The Mexican Food Banking Network (BAMX) reported a greater awareness of its environmental impact after participating in the pilot.

- Informing National Climate Policy: The food bank in Quito, Ecuador, has used the data collected through the FRAME pilot to engage with government representatives on the country’s national decarbonization platform, directly influencing policy discussions related to SDG 13.

Conclusion: The Role of Data in Advancing Climate and Development Goals

The GFN’s initiative highlights a critical evolution in the role of non-profits. While the viability of carbon credits as a primary funding tool remains debatable, the strategic value of the underlying data is clear. By meticulously tracking and reporting on their operations, food banks can provide robust, verifiable data that demonstrates a direct link between food waste reduction (SDG 12) and climate mitigation (SDG 13). This data is invaluable for national governments reporting on climate progress and helps integrate food systems into climate policy. Ultimately, this positions food banks not just as service providers for SDG 2, but as essential partners in the global effort to achieve a sustainable and climate-resilient future.

1. SDGs Addressed in the Article

The article discusses issues that are directly connected to several Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The analysis highlights the intersection of food security, environmental sustainability, and economic mechanisms.

-

SDG 2: Zero Hunger

This goal is addressed through the primary mission of food banks, which is to combat hunger by redistributing surplus food. The article states that food banks “rescuing unsold food from grocers and retailers and redistributing it to families and individuals in need.” This action directly contributes to ensuring access to food for vulnerable populations.

-

SDG 12: Responsible Consumption and Production

This is a central theme of the article, focusing on the problem of food waste. The article opens by stating, “Eight to 10 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions come from food wasted somewhere along its journey from farm to table.” The work of food banks in diverting this waste from landfills is a clear example of promoting responsible consumption patterns and reducing waste generation.

-

SDG 13: Climate Action

The article explicitly links food waste to climate change. It notes that when organic waste ends up in a landfill, “it emits methane, a powerful greenhouse gas.” The entire initiative of tracking avoided emissions and selling carbon credits is a direct climate action strategy. The article mentions the goal is to use data to “better aid decarbonization efforts.”

-

SDG 17: Partnerships for the Goals

The initiative described involves collaboration between various entities. The Global FoodBanking Network (a non-profit) is partnering with local food banks in multiple countries (Mexico, Ecuador), which in turn engage with national governments on “decarbonization platforms.” The carbon credit scheme itself is a partnership between the non-profits (sellers) and corporations (buyers), creating a public-private and civil society collaboration to achieve social and environmental goals.

2. Specific Targets Identified

Based on the article’s content, several specific SDG targets can be identified:

-

Target 2.1: End hunger and ensure access to safe, nutritious food

The article’s description of food banks’ work aligns directly with this target. By “rescuing unsold food… and redistributing it to families and individuals in need,” these organizations are working to ensure year-round access to food for the poor and vulnerable.

-

Target 12.3: Halve per capita global food waste

The article is fundamentally about reducing food waste at the retail level. The core activity of food banks is to intercept food that would otherwise be wasted. The FRAME methodology mentioned in the article is designed to quantify the impact of “diverting food from landfills,” which is a direct contribution to this target.

-

Target 12.5: Substantially reduce waste generation

By preventing food from ending up in landfills, food banks are contributing to the reduction of waste generation through prevention and reuse (for human consumption). The article highlights that the FRAME methodology only considers food “that would otherwise arrive at one of these destinations [landfill, compost, animal feed] but is then diverted by food banks.”

-

Target 13.2: Integrate climate change measures into policies and planning

The article provides a concrete example of this target in action. It mentions that a food bank in Quito, Ecuador, “has used the data it collected to have conversations with representatives from the national government about Ecuador’s decarbonization platform.” This shows how a non-governmental initiative can influence national climate planning.

-

Target 17.17: Encourage effective public, public-private and civil society partnerships

The entire carbon credit program described is a multi-stakeholder partnership. It involves The Global FoodBanking Network, local food banks, certification organizations like the Gold Standard, and private corporations that purchase the credits. This model is a clear example of the kind of partnership this target aims to promote.

3. Indicators Mentioned or Implied

The article mentions or implies several indicators that can be used to measure progress towards the identified targets:

-

Indicator for Target 12.3 (Food Waste Index)

The article implies the use of this indicator by discussing the quantification of food saved. An implied indicator is the total volume or weight of food rescued by food banks that would have otherwise been wasted at the retail level. The FRAME methodology is a tool to track this.

-

Indicator for Target 13.2 (Total greenhouse gas emissions)

A direct indicator is mentioned: the quantity of avoided greenhouse gas emissions. The article states that food banks “have recently started tracking their operations and quantifying how many emissions they’re avoiding.” The FRAME (Food Recovery to Avoid Methane Emissions) methodology is explicitly designed to calculate this, comparing emissions from food bank operations to the scenario where food goes to a landfill.

-

Indicator for Target 17.3 (Additional financial resources mobilized)

The article discusses carbon credits as an “alternative sources of funding” for food banks, especially as foreign aid is threatened. A clear indicator, therefore, is the amount of revenue generated from the sale of carbon credits, which represents a new financial resource mobilized for sustainable development activities.

4. Summary Table of SDGs, Targets, and Indicators

| SDGs | Targets | Indicators Identified in the Article |

|---|---|---|

| SDG 2: Zero Hunger | Target 2.1: By 2030, end hunger and ensure access by all people… to safe, nutritious and sufficient food all year round. | Amount of food redistributed to families and individuals in need. |

| SDG 12: Responsible Consumption and Production | Target 12.3: By 2030, halve per capita global food waste at the retail and consumer levels. Target 12.5: By 2030, substantially reduce waste generation through prevention, reduction, recycling and reuse. |

Volume of food diverted from landfills and redistributed for human consumption. |

| SDG 13: Climate Action | Target 13.2: Integrate climate change measures into national policies, strategies and planning. | Quantity of avoided greenhouse gas (methane) emissions, calculated using the FRAME methodology. Use of this data in discussions with national governments on decarbonization platforms. |

| SDG 17: Partnerships for the Goals | Target 17.17: Encourage and promote effective public, public-private and civil society partnerships. Target 17.3: Mobilize additional financial resources for developing countries from multiple sources. |

Revenue generated from the sale of carbon credits as an alternative funding source. The existence of the partnership between GFN, local food banks, corporations, and governments. |

Source: grist.org

What is Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0

;Resize=805#)