Your Outdoor Air Quality Monitor Could Lead to Safer Air for Everyone – WIRED

Report on Air Quality Monitoring and its Alignment with Sustainable Development Goals

This report analyzes the increasing role of personal and governmental air quality monitoring in the context of public health and global sustainability. It highlights the direct contributions of such monitoring to achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly those concerning health, sustainable communities, and environmental justice.

1.0 The State of Air Quality Monitoring and Data Accessibility

The landscape of air quality monitoring has transformed from a sparsely covered governmental function to a widely accessible data stream for citizens. This evolution is critical for advancing several SDGs.

- SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being): Increased access to real-time air quality data through government portals like AirNow and commercial applications empowers individuals to make informed decisions to protect their health from pollutants.

- SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities): The availability of localized data helps build resilient and sustainable urban environments by informing citizens about immediate environmental hazards.

- SDG 17 (Partnerships for the Goals): The proliferation of low-cost, citizen-owned monitors creates a powerful crowdsourced data network, filling gaps left by official monitoring stations and fostering a partnership between citizens, private technology companies, and public health bodies.

2.0 The Impact of Citizen Science on Community Health and Policy

Citizen-led monitoring has proven to be a catalyst for environmental action and policy change, directly supporting the objectives of sustainable urban development.

2.1 Case Study: Industrial Pollution and Community Action

A notable case in New York City demonstrates the power of citizen-generated data in achieving environmental justice and promoting community well-being.

- A resident’s personal air quality monitor detected persistently high levels of pollution (AQI over 100), inconsistent with official area-wide reports.

- The source was identified as a nearby concrete recycling center, which was releasing significant amounts of concrete dust (PM 2.5), a known health hazard.

- Data from a network of citizen-owned monitors provided evidence of a localized pollution “hotspot,” corroborating residents’ health concerns.

- This data-driven community advocacy, aligned with SDG 11.6 (reduce the adverse per capita environmental impact of cities, including air quality), led to political pressure and the subsequent relocation of the facility.

2.2 Case Study: Hyperlocal Pollution Sources

Monitoring also reveals the significant impact of micro-scale pollution sources, which official networks cannot capture.

- An illegal backyard fire pit was observed to raise local PM 2.5 levels to an unhealthy 160, while air quality a few blocks away remained good.

- This highlights the importance of hyperlocal data in protecting immediate personal health, a core tenet of SDG 3.

3.0 Regulatory Frameworks and Global Health Standards

Effective regulation is fundamental to protecting public health and achieving environmental sustainability. The disparity between national and international standards, and the political will to enforce them, directly impacts progress on the SDGs.

3.1 Health Risks of Particulate Matter (PM 2.5)

The primary pollutant of concern, PM 2.5, poses significant health risks that undermine SDG 3.

- These invisible particles can penetrate deep into the lungs and enter the bloodstream.

- Health effects include respiratory distress, cardiovascular disease, and other serious illnesses.

- The historic 1948 Donora Smog Event, which killed 20 people and sickened thousands, serves as a stark reminder of the fatal consequences of unregulated air pollution and was a catalyst for the Clean Air Act.

3.2 Regulatory Standards and Institutional Accountability

Governmental regulations are crucial for ensuring clean air, but their effectiveness depends on strong, science-based standards and enforcement, which relates to SDG 16 (Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions).

- The Biden administration strengthened the U.S. annual PM 2.5 standard to 9.0 µg/m³.

- This standard remains less stringent than the World Health Organization (WHO) guideline of 5 µg/m³.

- Proposed actions to reconsider these standards and repeal regulations on greenhouse gas emissions present a significant threat to progress on both SDG 3 and SDG 13 (Climate Action).

4.0 Addressing Inequities in Environmental Health

The burden of air pollution is not shared equally, creating a significant challenge for SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities).

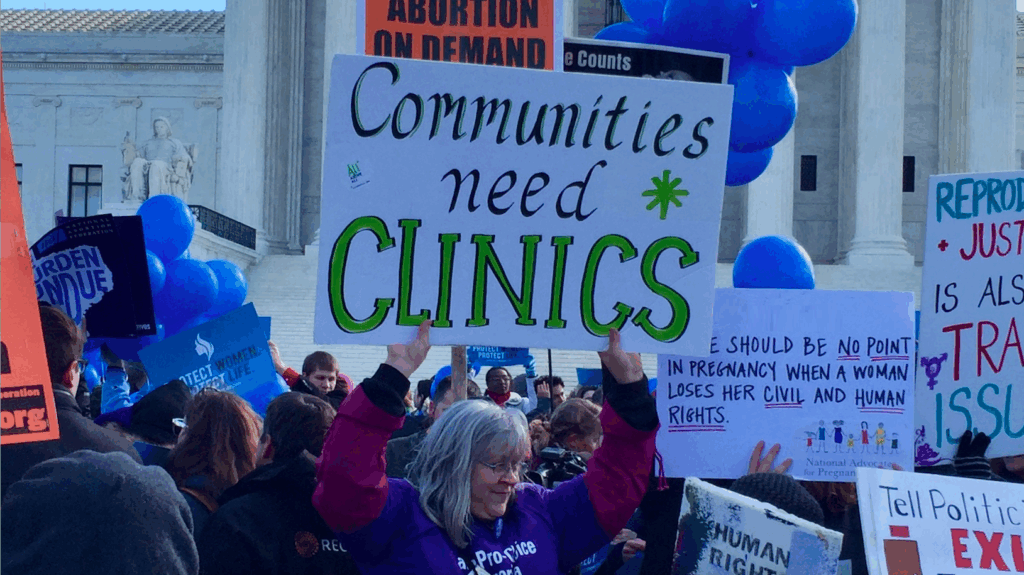

- Historically, communities of color and those with lower socioeconomic status are disproportionately located in areas with worse air quality.

- While personal monitors are valuable tools, their cost can be a barrier for the very communities most affected by pollution.

- This highlights a critical equity gap, where those with the greatest need for data and protection may have the least access to it. Prioritizing access to air purifiers and community-level monitoring programs is essential to mitigate this inequity.

Analysis of Sustainable Development Goals in the Article

1. Which SDGs are addressed or connected to the issues highlighted in the article?

The article on air quality monitoring addresses several Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by focusing on environmental health, urban living conditions, climate policy, inequality, and the role of institutions and public information.

-

SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being

This goal is central to the article, which repeatedly connects air pollution to negative health outcomes. It discusses how poor air quality, specifically from particulate matter like PM 2.5, can lead to severe health problems.

-

SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities

The article highlights issues of urban air quality, particularly in New York City. It examines the impact of industrial activities, like a concrete recycling center, on the local environment and the well-being of residents, which is a key concern for sustainable urban development.

-

SDG 13: Climate Action

This goal is addressed through the discussion of government policies on greenhouse gas emissions. The article mentions the potential repeal of these regulations, which directly impacts national and global efforts to combat climate change.

-

SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities

The article touches upon environmental justice, stating that “communities of color and lower socioeconomic backgrounds live in areas with worse air quality.” This points to the unequal distribution of environmental burdens, a key aspect of inequality.

-

SDG 16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions

This goal is relevant through the article’s discussion of government regulations (EPA standards), the need for effective and transparent monitoring by institutions, and the role of public access to information. The citizen-led monitoring and activism described are examples of participatory decision-making.

2. What specific targets under those SDGs can be identified based on the article’s content?

Based on the issues discussed, several specific SDG targets can be identified:

-

Target 3.9: Substantially reduce deaths and illnesses from pollution

The article directly supports this target by detailing the health risks of air pollution. It mentions that PM 2.5 can “enter the deepest parts of the lungs, passing into the bloodstream” and “cause a host of illnesses, respiratory distress, and cardiovascular disease.” The historical reference to the “Donora Smog Event,” where “20 people died and nearly 6,000 were sickened,” further emphasizes the link between air pollution and mortality/morbidity.

-

Target 11.6: Reduce the environmental impact of cities

This target is addressed through the focus on urban air quality. The article describes a local pollution source in New York City—a “concrete recycling center”—and how its “concrete dust” led to an “uptick in bad air.” The use of personal and crowdsourced air quality monitors to track pollution on a micro-local level within a city is a direct engagement with this target.

-

Target 13.2: Integrate climate change measures into national policies

The article references this target by discussing national-level environmental policy. It notes that the “Trump administration also wants to repeal greenhouse gas emissions regulations” and quotes a proposal finding that “GHG emissions from fossil fuel-fired power plants do not contribute significantly to dangerous air pollution.” This represents a significant move away from integrating climate measures into national policy.

-

Target 16.10: Ensure public access to information

This target is highlighted by the article’s emphasis on making air quality data available to the public. It mentions government tools like “AirNow,” state-level interactive maps, and, most prominently, “crowdsourced real-time map” platforms like PurpleAir, AirGradient, and IQAir. These tools empower citizens with data, allowing them to understand their environment and “fill the gaps in air monitoring.”

3. Are there any indicators mentioned or implied in the article that can be used to measure progress towards the identified targets?

The article mentions or implies several indicators that can be used to measure progress:

-

Indicator 3.9.1: Mortality rate attributed to household and ambient air pollution

While not providing current mortality rates, the article implies this indicator by referencing historical events like the Donora Smog, which caused deaths, and by linking PM 2.5 exposure to deadly conditions like cardiovascular disease. The entire premise of monitoring air quality is to mitigate these health risks.

-

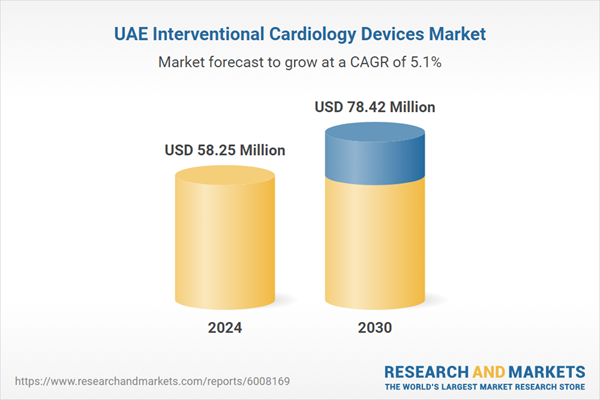

Indicator 11.6.2: Annual mean levels of fine particulate matter (e.g., PM2.5) in cities

This is the most explicit indicator in the article. It provides specific measurements of PM 2.5, which is a key metric for urban air quality. Examples include:

- The Biden administration strengthening the standard to “9.0 micrograms per cubic meter (µg/m³).”

- The stricter World Health Organization (WHO) guideline of “5 PM 2.5.”

- Local readings from a personal monitor showing an “unhealthy 160 PM 2.5” due to a fire pit.

- The use of the Air Quality Index (AQI), where “100 or more is unhealthy for sensitive groups.”

-

Indicator of Public Access to Information (related to Target 16.10)

The article provides concrete examples that serve as qualitative indicators of public access to information. These include the existence and use of:

- Government websites like AirNow.gov.

- Interactive data maps provided by the EPA and New York State.

- Crowdsourced maps from companies like PurpleAir, which aggregate data from citizen-owned monitors, making hyper-local air quality data publicly available. The article notes, “The more people who own outdoor air monitors and link them to the crowdsourced maps, the more accurate the air quality readings will be.”

4. Table of SDGs, Targets, and Indicators

| SDGs | Targets | Indicators |

|---|---|---|

| SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being | 3.9: By 2030, substantially reduce the number of deaths and illnesses from hazardous chemicals and air, water and soil pollution and contamination. | 3.9.1 (Implied): Mortality and morbidity rates attributed to ambient air pollution, as referenced by the discussion of the Donora Smog Event and illnesses caused by PM 2.5 (respiratory distress, cardiovascular disease). |

| SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities | 11.6: By 2030, reduce the adverse per capita environmental impact of cities, including by paying special attention to air quality. | 11.6.2: Annual mean levels of fine particulate matter (PM2.5). The article explicitly provides multiple PM 2.5 and AQI values, such as the national standard of 9.0 µg/m³, the WHO guideline of 5 µg/m³, and local readings of “160 PM 2.5.” |

| SDG 13: Climate Action | 13.2: Integrate climate change measures into national policies, strategies and planning. | (Descriptive): The existence and enforcement of national policies on greenhouse gases. The article points to a negative indicator by mentioning the proposal to “repeal greenhouse gas emissions regulations.” |

| SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities | (Related to 10.2/10.3): Promote social inclusion and reduce inequalities of outcome. | (Descriptive): Disparities in environmental quality based on socioeconomic status and race. The article notes that “communities of color and lower socioeconomic backgrounds live in areas with worse air quality.” |

| SDG 16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions | 16.10: Ensure public access to information and protect fundamental freedoms. | (Descriptive): The availability and use of public information platforms. The article cites government websites (AirNow), state and federal interactive maps, and crowdsourced data maps (PurpleAir, AirGradient) as key tools for public information. |

Source: wired.com

What is Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0

_1.png?#)