New study finds the gender earnings gap could be halved if we reined in the long hours often worked by men – The Conversation

Report on the Impact of Extended Work Hours on Gender Equality and Sustainable Development Goals

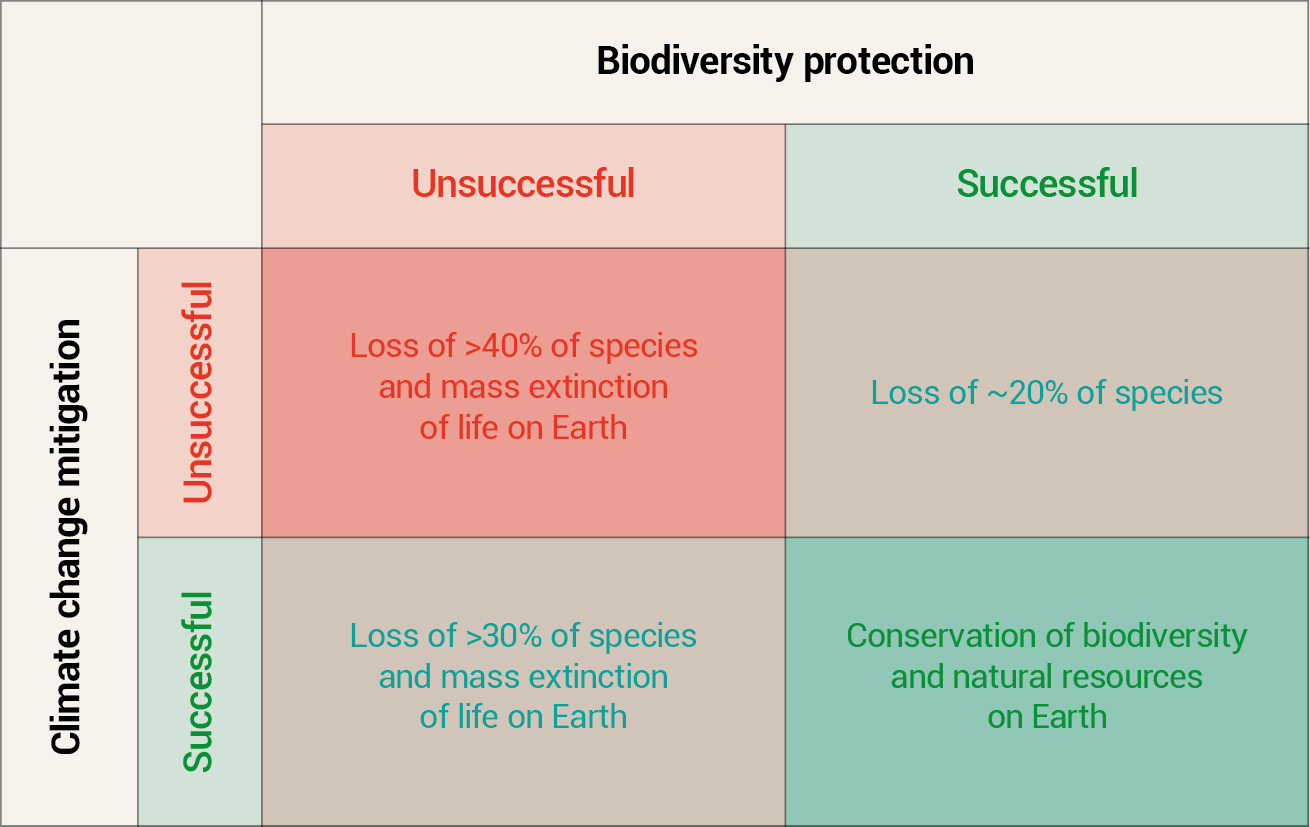

An analysis of work patterns in heterosexual couple households reveals that the prevalence of long working hours, particularly among men, significantly contributes to gender inequality. This dynamic creates a substantial barrier to achieving key Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including SDG 5 (Gender Equality), SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth), and SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities).

Research Methodology and Scope

The findings are based on a study of 3,000 to 6,000 heterosexual couples in Australia and Germany between 2002 and 2019. The research utilized a two-stage instrumental variable Oaxaca-Blinder decomposition method to model the relationship between partners’ paid and unpaid work hours and their subsequent impact on earnings.

Initial Findings on Gender-Based Economic Disparities

The study identified a significant gender earnings gap in both countries, a direct challenge to SDG 8’s target for equal pay for work of equal value.

- Australia: Men earned, on average, $536 more per week than women.

- Germany: Men earned, on average, €400 more per week than women.

Approximately half of this income disparity was found to be a direct result of men working extended hours. This arrangement is facilitated by women reducing their own paid work hours to manage a disproportionate share of unpaid domestic and care responsibilities, a critical issue highlighted in SDG 5.4, which calls for the recognition and valuation of unpaid care work.

The Intra-Household “Subsidy” Effect and its Impact on SDGs

How Unpaid Labor Drives Inequality

The research demonstrates that one partner’s capacity to work long hours is often dependent on the other partner undertaking a greater share of unpaid household duties. This “subsidy” of time is a primary driver of the gender gap in both work hours and earnings, undermining the principles of shared responsibility central to SDG 5.

The consequences of this imbalance are significant:

- It perpetuates economic inequality between genders, hindering progress toward SDG 10.

- It institutionalizes a model of work that conflicts with the principles of decent work and work-life balance as outlined in SDG 8.

- It devalues unpaid care and domestic work, directly contravening the objective of SDG 5.4.

Modeling an Equitable Framework Aligned with SDG Principles

The study modeled a scenario where the intra-household time “subsidy” was eliminated to assess the potential for a more equitable distribution of paid and unpaid labor.

Projected Impact on Work Hours and Earnings

Removing the reliance on one partner’s unpaid labor to support the other’s extended paid work hours would lead to a dramatic reduction in gender-based disparities.

- Work Hour Gap Reduction: The weekly work hour gap would decrease by 58% in Australia and 47% in Germany.

- Earnings Gap Reduction: The gender earnings gap would shrink by 43% in Australia and 25% in Germany.

A Model for Decent Work (SDG 8)

This equitable model suggests a shift toward more sustainable work patterns. In Australia, men’s average weekly hours would decrease to approximately 41, closer to the legislated 38-hour week, while women’s paid hours would increase to 36. This adjustment promotes a healthier work-life balance and moves toward the SDG 8 goal of decent work for all.

Conclusion: Reining in Excessive Hours as a Strategy for Sustainable Development

The culture of long working hours is a systemic impediment to achieving gender equality and sustainable economic growth. It relies on an unequal distribution of unpaid labor within households, which directly widens the gender earnings gap.

To advance the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, a new focus on regulating excessive work hours is required. Such a policy shift would represent a significant step toward:

- Achieving SDG 5: By promoting shared domestic responsibilities and reducing the economic penalty women face for unpaid care work.

- Fulfilling SDG 8: By fostering decent work environments that do not depend on unsustainable hours.

- Advancing SDG 10: By directly reducing a key driver of income inequality within nations.

Analysis of Sustainable Development Goals in the Article

1. Which SDGs are addressed or connected to the issues highlighted in the article?

-

SDG 5: Gender Equality

- The article’s central theme is the gender inequality present in heterosexual couple households, specifically concerning work hours and earnings. It investigates how men’s long working hours are “subsidised” by women undertaking a larger share of unpaid domestic and care work, which directly impacts women’s economic standing. The entire study discussed aims to quantify and explain the drivers of the gender earnings and work hours gaps, which is a core component of SDG 5.

-

SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth

- The article addresses issues of decent work by questioning workplace cultures that encourage or demand excessively long hours. It discusses the gender pay gap, the disparity in weekly earnings, and how these factors relate to the number of hours worked. This connects to SDG 8’s goal of achieving full and productive employment and decent work for all, including equal pay for work of equal value.

2. What specific targets under those SDGs can be identified based on the article’s content?

-

Target 5.4: Recognize and value unpaid care and domestic work through the provision of public services, infrastructure and social protection policies and the promotion of shared responsibility within the household and the family as nationally appropriate.

- The article directly addresses this target by demonstrating the economic consequences of unbalanced unpaid work. It states, “one partner’s paid work hours can increase when the other partner does more unpaid (household) work.” The study’s modeling of a more even split of home duties and its effect on closing the earnings gap highlights the economic value of this unpaid work and the importance of shared responsibility.

-

Target 8.5: By 2030, achieve full and productive employment and decent work for all women and men… and equal pay for work of equal value.

- This target is central to the article’s analysis. The text explicitly discusses the “gender earnings gap” ($536 in Australia, €400 in Germany) and the “gender pay gap in hourly pay” (11.1% in Australia). The research shows how unequal work hours contribute significantly to this gap, preventing women from achieving full economic parity and equal pay relative to their male partners. The article concludes by suggesting that reining in excess hours is a key focus for achieving equality.

3. Are there any indicators mentioned or implied in the article that can be used to measure progress towards the identified targets?

-

Indicator 5.4.1: Proportion of time spent on unpaid domestic and care work, by sex.

- This indicator is implicitly central to the study described. The article explains that the research model is based on the dynamic where one partner (typically the woman) does more unpaid work, enabling the other (the man) to work longer paid hours. The study’s recalculation of work hours based on a more even split of “home duties” directly relates to measuring and understanding the impact of time spent on unpaid work.

-

Indicator 8.5.1: Average hourly earnings of female and male employees.

- The article explicitly provides data relevant to this indicator. It states, “According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, the average gender gap in hourly pay is 11.1%.” This figure is a direct measurement used to track progress toward equal pay.

-

Implied Indicator: Gender gap in average weekly earnings.

- The article provides specific figures for this measure, stating that in couple households, “men earned on average $536 more than women every week” in Australia and the “weekly gender earnings gap was €400” in Germany. It also notes the overall average weekly earnings gap in Australia is 26.4%. This serves as a key indicator of economic inequality.

-

Implied Indicator: Gender gap in hours worked.

- The article focuses heavily on the “work hour gap.” It quantifies the potential reduction in this gap if domestic duties were shared more evenly: “The weekly work hour gap shrank to 5.1 hours in Australia (a 58% reduction) and 6.9 hours in Germany (a 47% reduction).” This gap is a critical measure of women’s participation in the paid workforce.

4. Table of SDGs, Targets, and Indicators

| SDGs | Targets | Indicators |

|---|---|---|

| SDG 5: Gender Equality | Target 5.4: Recognize and value unpaid care and domestic work and promote shared responsibility within the household. | Indicator 5.4.1 (Implied): The article’s analysis is based on the unequal proportion of time spent on unpaid domestic work between men and women in heterosexual couples. |

| SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth | Target 8.5: Achieve full and productive employment and decent work for all, and equal pay for work of equal value. |

|

Source: theconversation.com

What is Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0