Air pollution raises risk of dementia, say Cambridge scientists – The Guardian

Report on the Nexus of Air Pollution, Dementia, and Sustainable Development Goals

Executive Summary

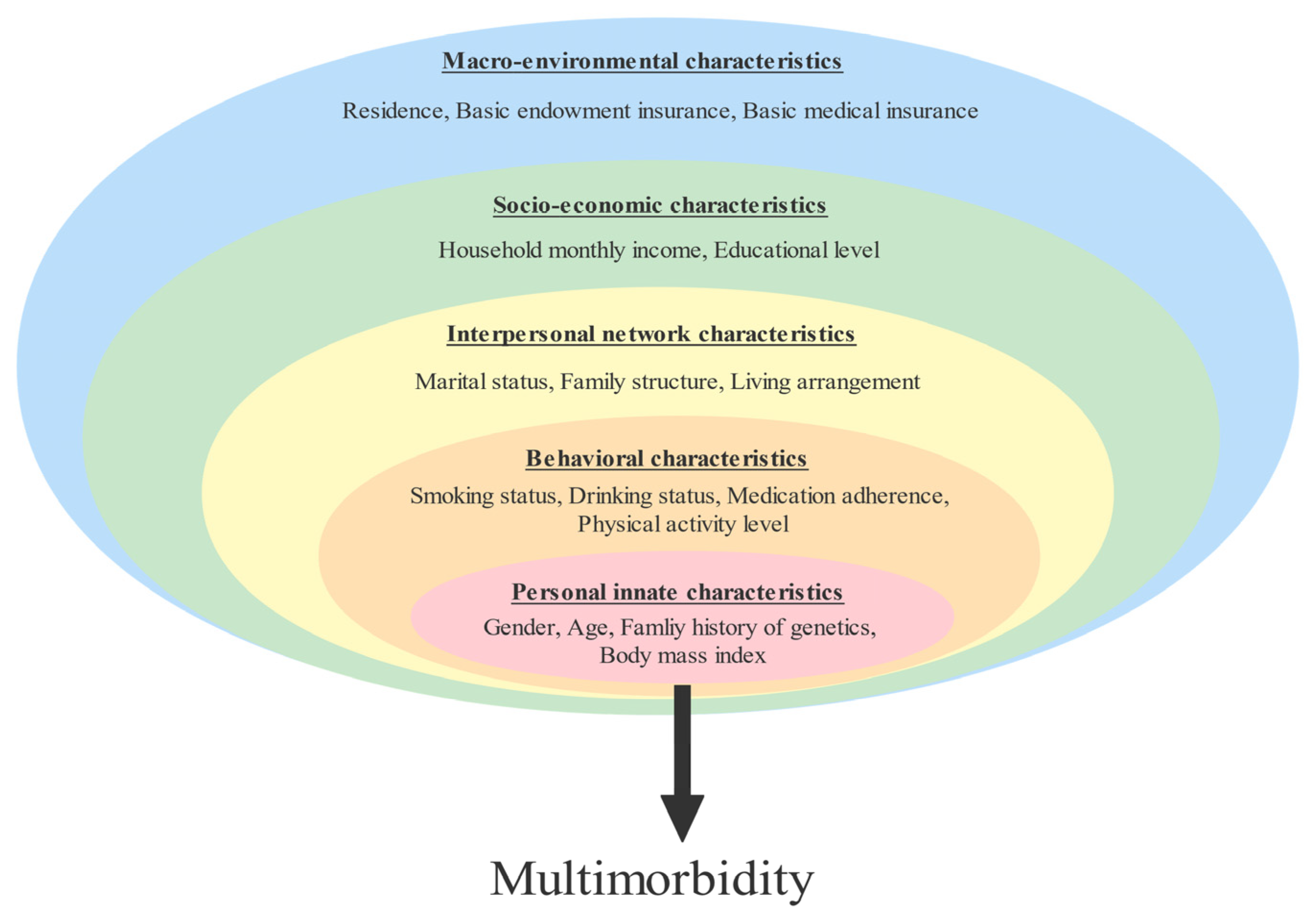

A comprehensive systematic review conducted by the University of Cambridge has established a statistically significant link between exposure to specific air pollutants and an increased risk of developing dementia. This report analyzes these findings through the lens of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), highlighting the critical intersection of public health, urban planning, and environmental policy. The research underscores the urgency of addressing air quality not only as a health imperative but as a core component of achieving sustainable development, particularly SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being) and SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities).

Key Findings of the Comprehensive Review

The study, published in The Lancet Planetary Health, represents the most extensive analysis to date on this topic. Key parameters of the research include:

- A systematic review of 51 individual studies.

- Analysis of data from over 29 million participants with at least one year of exposure.

- Identification of a positive and statistically significant association between dementia and three specific pollutants.

Identified Pollutants and Associated Risks

The research confirmed a direct correlation between dementia risk and long-term exposure to the following pollutants:

- Particulate Matter (PM2.5): Originating from vehicle emissions, power plants, and woodburning. The study found that for every 10 micrograms per cubic metre (µg/m³) increase in PM2.5, an individual’s relative risk of dementia increases by 17%.

- Nitrogen Dioxide (NO2): Primarily generated by the burning of fossil fuels in transportation and industry.

- Soot (Black Carbon): Sourced from vehicle exhausts and wood burning. An equivalent increase in soot exposure was linked to a 13% rise in dementia risk.

These pollution levels were reportedly met or exceeded at various roadside locations in major UK cities during 2023, demonstrating a direct and ongoing threat to urban populations.

Implications for SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being

The findings have profound implications for SDG 3, which aims to ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages.

- Target 3.9: The report directly supports the objective to “substantially reduce the number of deaths and illnesses from hazardous chemicals and air…pollution and contamination.” Dementia, which currently affects 57 million people globally and is projected to impact 150 million by 2050, is now more clearly defined as an illness linked to air pollution.

- Target 3.8: The rising prevalence of dementia places an immense burden on patients, families, and healthcare systems. Mitigating air pollution as a key risk factor can help ease this pressure, contributing to the goal of achieving universal health coverage and sustainable healthcare systems.

Connection to SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities

The sources of the identified pollutants are intrinsically linked to urban environments, making air quality a central issue for achieving SDG 11.

- Target 11.6: This target calls for reducing the adverse per capita environmental impact of cities, with a special focus on air quality. The study’s findings provide a compelling health-based argument for governments and municipalities to accelerate efforts to reduce traffic emissions, transition away from fossil fuels, and regulate industrial pollution.

Broader Interlinkages with Other SDGs

Addressing the challenge of air pollution offers co-benefits across multiple Sustainable Development Goals.

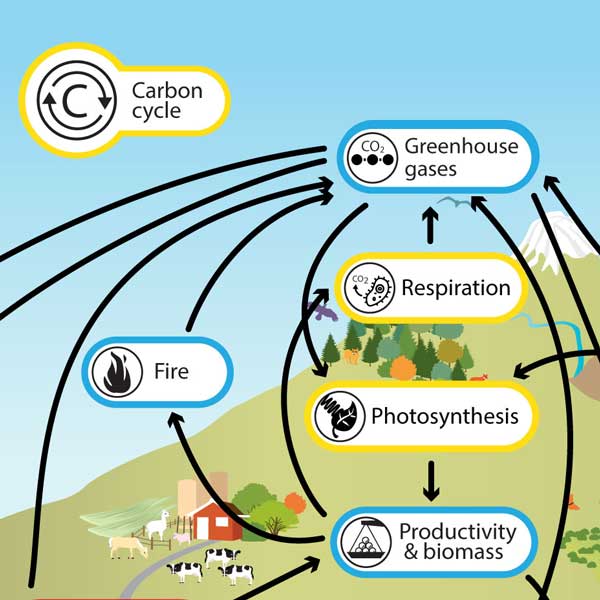

- SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy): Tackling pollutants like NO2 and PM2.5 at their source necessitates a shift from fossil fuels to cleaner energy sources, aligning with the goal of increasing the share of renewable energy.

- SDG 13 (Climate Action): The combustion of fossil fuels is a primary driver of both air pollution and climate change. Therefore, policies aimed at improving air quality are synergistic with climate action strategies.

- SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities): The researchers noted a limitation in that most analyzed studies involved participants from high-income countries. Future research must include marginalized communities, which are often disproportionately exposed to higher levels of air pollution, to ensure equitable health outcomes.

Policy Recommendations and Conclusion

Experts responding to the study emphasize that air pollution is a major modifiable risk factor for dementia that requires decisive government action. The report reinforces calls for a bold, cross-governmental approach that integrates health, environment, and urban planning policies. Tackling air pollution is not merely an environmental issue but a critical strategy for advancing long-term public health, promoting social equity, and achieving global sustainability targets.

Analysis of Sustainable Development Goals in the Article

Which SDGs are addressed or connected to the issues highlighted in the article?

-

SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being

This is the most central SDG in the article. The text directly links exposure to air pollution with an increased risk of dementia, a significant health issue. It discusses the global prevalence of the disease (“about 57 million people worldwide”), the burden on patients and healthcare systems, and the importance of prevention. The call to tackle air pollution to reduce this health risk directly aligns with ensuring healthy lives and promoting well-being for all at all ages.

-

SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities

The article explicitly connects the problem to urban environments. It identifies the sources of pollutants as “vehicle emissions, power plants and woodburning stoves,” which are concentrated in cities. It also names specific cities like “central London, Birmingham and Glasgow” where pollution levels are dangerously high. This directly relates to the goal of making cities inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable, with a key component being the management of urban air quality.

-

SDG 7: Affordable and Clean Energy

This SDG is implicitly connected. The article identifies “power plants” and “the burning of fossil fuels” as primary sources of nitrogen dioxide and PM2.5. Addressing the issue of air pollution at its source necessitates a transition towards cleaner energy systems, which is the core objective of SDG 7.

-

SDG 13: Climate Action

An indirect connection to SDG 13 is made when the article states that “Tackling air pollution can deliver long-term health, social, climate and economic benefits.” The sources of the air pollutants mentioned, such as vehicle emissions and the burning of fossil fuels, are also the primary drivers of climate change. Therefore, actions taken to improve air quality would have co-benefits for climate action.

What specific targets under those SDGs can be identified based on the article’s content?

-

SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being

- Target 3.4: By 2030, reduce by one-third premature mortality from non-communicable diseases through prevention and treatment and promote mental health and well-being. The article focuses on dementia, a non-communicable disease, and emphasizes prevention by addressing a key risk factor, air pollution. Dr. Khreis is quoted saying that tackling pollution can “reduce the immense burden on patients, families, and caregivers.”

- Target 3.9: By 2030, substantially reduce the number of deaths and illnesses from hazardous chemicals and air, water and soil pollution and contamination. The entire article is built on this premise, providing evidence that specific air pollutants (PM2.5, nitrogen dioxide, soot) cause illness (dementia).

-

SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities

- Target 11.6: By 2030, reduce the adverse per capita environmental impact of cities, including by paying special attention to air quality. The article directly addresses this target by highlighting that PM2.5 and soot levels “approached or exceeded” dangerous levels “at roadside locations in central London, Birmingham and Glasgow,” demonstrating the adverse environmental impact of cities on human health.

Are there any indicators mentioned or implied in the article that can be used to measure progress towards the identified targets?

-

Indicator for Target 3.9 (Reduce illness from air pollution)

The article provides a specific measure of health risk that can be used as an indicator. It states that “for every 10 micrograms per cubic metre of PM2.5, an individual’s relative risk of dementia would increase by 17%.” This quantifiable link between pollutant concentration and disease risk is a direct way to measure the health impact of air pollution.

-

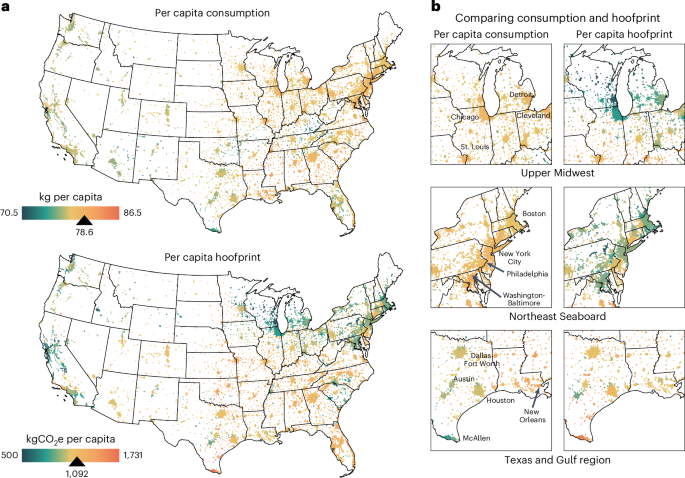

Indicator for Target 11.6 (Reduce adverse environmental impact of cities)

The article directly references the core component of Indicator 11.6.2 (Annual mean levels of fine particulate matter (e.g. PM2.5) in cities). It mentions specific pollutants like “PM2.5,” “nitrogen dioxide,” and “soot.” It also provides a quantitative benchmark, noting that levels of these pollutants in major UK cities “approached or exceeded” 10 micrograms per cubic metre, which is the threshold linked to a 17% increased risk of dementia.

-

Indicator for Target 3.4 (Reduce premature mortality from non-communicable diseases)

The article provides data on the prevalence of dementia, a non-communicable disease. It states that the illness affects “about 57 million people worldwide” and is projected to increase to “150m cases by 2050.” In the UK, “about 982,000 people have the illness.” These figures serve as baseline indicators for the burden of this specific non-communicable disease, and tracking these numbers over time would measure progress.

SDGs, Targets, and Indicators Table

| SDGs | Targets | Indicators |

|---|---|---|

| SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being |

3.4: Reduce premature mortality from non-communicable diseases through prevention.

3.9: Substantially reduce the number of deaths and illnesses from air pollution. |

Prevalence of dementia (currently 57 million globally, 982,000 in the UK).

Increased relative risk of dementia per unit of pollutant (e.g., a 17% increase in risk for every 10 µg/m³ of PM2.5). |

| SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities | 11.6: Reduce the adverse per capita environmental impact of cities, paying special attention to air quality. | Annual mean levels of fine particulate matter (PM2.5) and soot in cities (e.g., levels in London, Birmingham, and Glasgow approaching or exceeding 10 µg/m³). |

| SDG 7: Affordable and Clean Energy | 7.2 (Implied): Increase substantially the share of renewable energy in the global energy mix. | The article identifies “power plants” and “the burning of fossil fuels” as sources of pollution, implying that a shift away from these sources is necessary. |

| SDG 13: Climate Action | 13.2 (Implied): Integrate climate change measures into national policies, strategies and planning. | The article mentions that tackling air pollution delivers “climate benefits” and calls for a “cross-government approach,” linking air quality policy with broader environmental and climate strategies. |

Source: theguardian.com

What is Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0