Challenging overfishing: The craft fishers of Peninsula Valdés – Buenos Aires Times

Report on Artisanal Shellfish Diving in Península Valdés and its Alignment with Sustainable Development Goals

Introduction: A Case Study in Sustainable Marine Resource Management

This report examines the artisanal shellfish diving community in Playa Larralde, Península Valdés, Argentina. It analyzes the practice as a model of sustainable economic activity that aligns with several United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), while also facing significant threats from industrial activities and a lack of institutional support.

SDG 14: Life Below Water – Conservation and Sustainable Use of Marine Resources

A Low-Impact Production Model

The primary fishing method employed by the community is selective, low-impact diving for shellfish such as Magellan mussels and scallops. This practice was developed in the 1970s through a partnership between scientists and local fishermen to prevent the marine ecosystem degradation seen in the neighboring San Matías Gulf. This approach directly supports the targets of SDG 14.

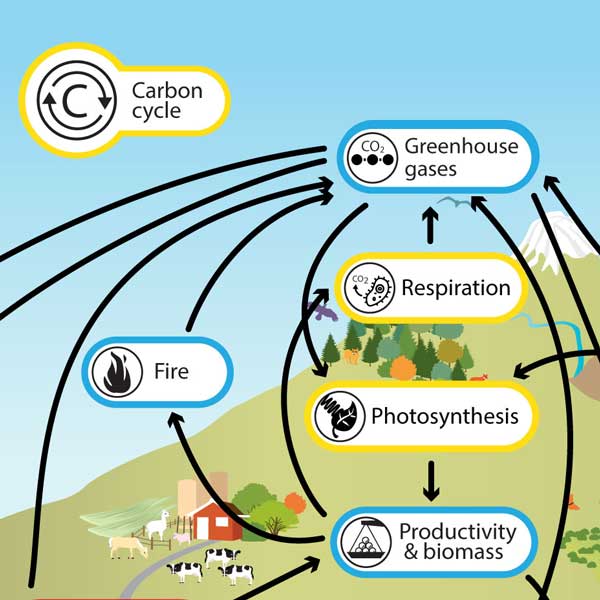

- Conservation of Biodiversity: The method avoids the destructive “raking” of the seabed common in industrial fishing, preserving the habitat for a wide variety of molluscs, crustaceans, and fish.

- Sustainable Harvesting: Fishermen practice self-regulation to prevent over-exploitation. As one fisherman noted, “We can’t pillage the gulf, otherwise we won’t even have seeds to sow,” demonstrating a commitment to maintaining fish stocks for future generations (Target 14.4).

- Ecosystem Health: The health of the San José and Nuevo gulfs is critical, supporting not only the fishery but also significant populations of southern right whales and other marine life. The artisanal practice is the only activity permitted to extract natural resources within the protected World Heritage area.

Threats to Marine Ecosystems

Despite the sustainable practices of the local community, the marine environment faces significant external threats:

- Resource Depletion: Fishermen report a swift decline in resources. One account noted that where 40 trays of scallops could be harvested in two hours three months prior, nothing was found after five years, indicating severe pressure on marine stocks.

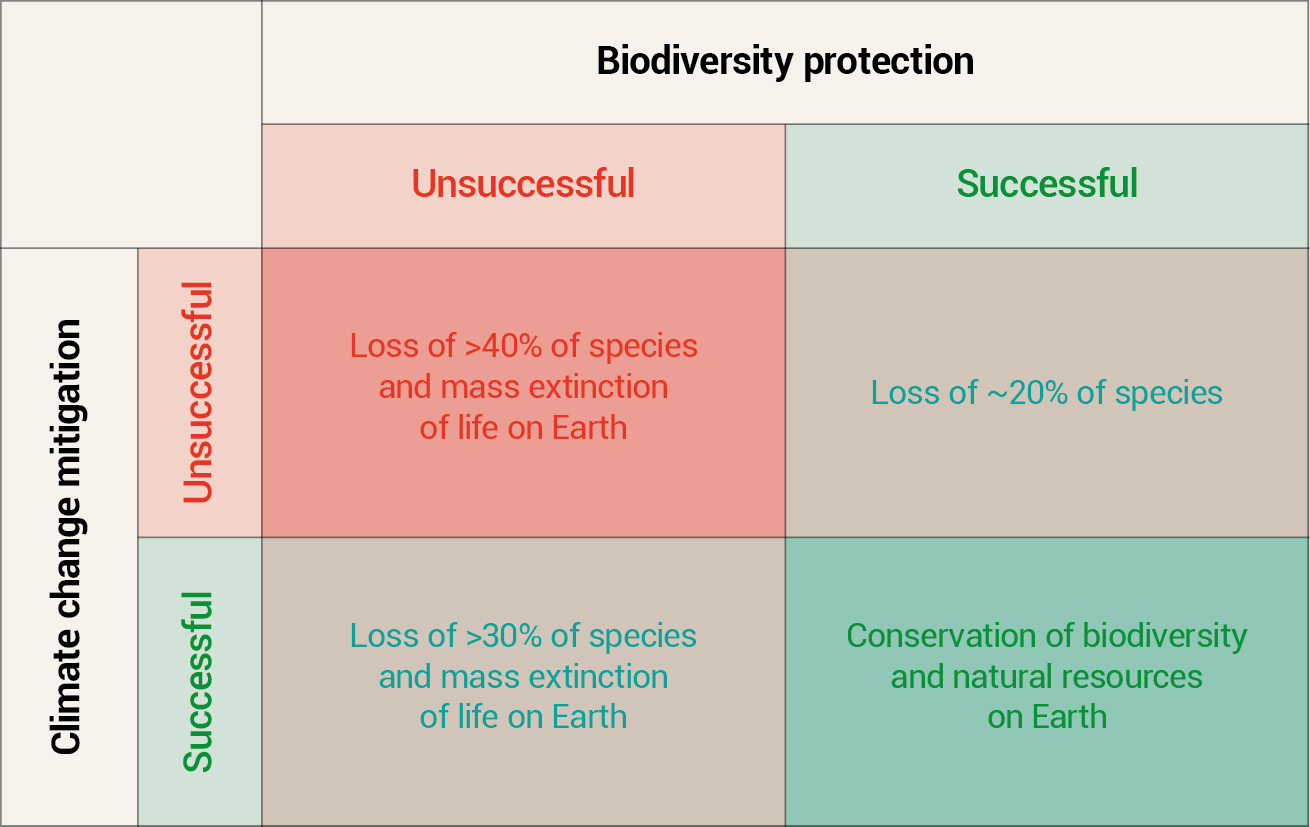

- Fossil Fuel Development: A proposed oil pipeline from the Vaca Muerta oilfield, terminating at a new port less than 100 kilometers away, poses a severe risk. Experts warn of pollution from micro-spills, which would create a “dirty environment” with a highly negative impact on the region’s unique biodiversity (Target 14.2).

SDG 8 & SDG 1: Decent Work, Economic Growth, and No Poverty

The Artisanal Economy: A Model of Localized Growth

Artisanal fishing represents a “popular economy” that provides a livelihood for the community. However, it is characterized by economic precarity and challenging working conditions, highlighting the need for progress towards SDG 8 (Decent Work) and SDG 1 (No Poverty).

- Economic Instability: Income is highly variable. A successful day can yield a significant return, but poor conditions or low catch can result in negligible earnings. High operational costs for fuel, equipment, and boat maintenance further impact profitability.

- Precarious Working Conditions: The work is physically demanding and hazardous, involving deep-water diving and decompression risks.

- Lack of Social Protection: Fishermen operate with minimal social security, healthcare, or pension provisions, leaving them vulnerable. This underscores a deficit in achieving decent work for all (Target 8.8) and requires accompanying policies to improve conditions.

SDG 11 & SDG 12: Sustainable Communities and Responsible Production

A Legacy of Sustainable Practices

The fishing community of Playa Larralde embodies the principles of a sustainable community (SDG 11) built upon a foundation of responsible production (SDG 12).

- Intergenerational Knowledge: The craft of selective diving is passed down through generations, preserving a unique cultural heritage and a deep, practical understanding of the marine environment. This knowledge is crucial for sustainable resource management.

- Community Resilience: The community has organized through institutions like the Puerto Madryn Artisanal Fishermen Association (established 1993) to advocate for their trade and improve its visibility.

- Contribution to Food Sovereignty: While 95% of fish from Argentine waters is exported, this local fishery offers a model for a domestic food system, contributing to discussions on food sovereignty and responsible consumption patterns.

SDG 17: Partnerships for the Goals

Collaboration Between Science and Community

The success and survival of this sustainable fishing model are rooted in effective partnerships, a key component of SDG 17.

- Scientist-Fishermen Collaboration: The historical collaboration, initiated by biologist José María ‘Lobo’ Orensanz, to replace destructive fishing methods with sustainable diving is a foundational example of a successful partnership.

- Ongoing Research: Researchers like Ana Cinti continue to work with the community, documenting their practices and advocating for the recognition of their socio-ecological value. This partnership demonstrates how scientific knowledge and traditional knowledge can be integrated to achieve sustainability goals.

Conclusion

The artisanal fishing community of Península Valdés is a valuable example of a production system that integrates environmental stewardship, economic livelihood, and cultural heritage, aligning with multiple SDGs. However, its continued existence is threatened by industrial pressures and a lack of supportive policies. To safeguard this model and advance the SDGs, it is critical to strengthen institutional support, implement robust environmental protections, and formally recognize the value of the community’s traditional ecological knowledge in regional marine management.

Which SDGs are addressed or connected to the issues highlighted in the article?

-

SDG 14: Life Below Water

- The article is centered on the marine ecosystem of Península Valdés. It discusses the sustainable harvesting of shellfish (mussels, scallops) by artisanal divers, contrasting it with the destructive impact of industrial fishing (“desertification fishing”). It highlights the importance of conserving marine biodiversity and the direct threat posed by a proposed oil pipeline, which could lead to “a zone of highly negative impact for the species present.” The fishermen’s philosophy, “We can’t pillage the gulf, otherwise we won’t even have seeds to sow,” directly embodies the goal of conserving and sustainably using marine resources.

-

SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth

- The article describes artisanal fishing as a “sustainable and popular economy” that provides a livelihood for generations of families. However, it also details the precarious nature of this work, pointing to a lack of “decent work.” It mentions the high operational costs, income volatility (“on a bad day you can dive for five hours and not even make 50 pesos”), physical risks (decompression, entanglement with whales), and the absence of social safety nets (“almost zero social security, healthcare or pension payments”).

-

SDG 12: Responsible Consumption and Production

- The practices of the artisanal fishermen are presented as a model of sustainable production. Their method of patient, low-impact diving is a “sustainable… alternative” to industrial methods that are “like a rake on the sea bed.” This conscious effort to manage resources sustainably to ensure future availability (“to avoid… to go all the way”) is a clear example of responsible production patterns.

-

SDG 1: No Poverty

- Artisanal fishing is the primary source of income for the families in Playa Larralde. The article notes that on a good day, a diver can earn a significant amount (“100,000 pesos in your pocket”), which is crucial for their economic survival. The trade represents a “popular economy” that, while precarious, provides a means to escape poverty in a remote region.

-

SDG 17: Partnerships for the Goals

- The article highlights a key partnership that has been crucial for the survival of this sustainable practice. It mentions the “joint work between scientists and fishermen” that began in the 1970s, initiated by biologist José María ‘Lobo’ Orensanz. This collaboration led to the adoption of more environmentally-friendly fishing methods. The ongoing work of researchers like Ana Cinti, who documents and supports the fishers, further exemplifies this multi-stakeholder collaboration for sustainability.

What specific targets under those SDGs can be identified based on the article’s content?

-

Target 14.4: End overfishing and destructive fishing practices

- This target aims to “effectively regulate harvesting and end overfishing… and destructive fishing practices and implement science-based management plans.” The article directly addresses this by describing the fishermen’s low-impact diving as an alternative to the “desertification fishing” and “rake on the sea bed” methods of industrial trawlers. Their self-regulation to avoid pillaging the gulf is a form of implementing a sustainable management plan.

-

Target 14.b: Provide access for small-scale artisanal fishers to marine resources and markets

- The entire narrative is focused on the lives of small-scale artisanal fishers and their dependence on access to the marine resources of the San José Gulf. The article notes that they are recognized in the World Heritage site’s plan as “the only activity permitted to extract natural resources within the protected area,” which is a formal recognition of their access rights.

-

Target 8.8: Protect labour rights and promote safe and secure working environments

- The article highlights the significant risks involved in the trade, such as decompression sickness and encounters with whales, stating it is a “risky job.” Furthermore, it explicitly points out the lack of social protection, noting “almost zero social security, healthcare or pension payments.” This directly relates to the need to promote safer working environments and protect labor rights for these workers.

-

Target 12.2: Achieve the sustainable management and efficient use of natural resources

- The fishermen’s conscious effort to preserve the shellfish populations is a direct application of this target. José Signorelli’s statement, “We can’t pillage the gulf, otherwise we won’t even have seeds to sow,” perfectly encapsulates the principle of sustainable management to ensure the long-term availability of natural resources.

Are there any indicators mentioned or implied in the article that can be used to measure progress towards the identified targets?

-

Qualitative assessment of fish stocks (Proxy for Indicator 14.4.1: Proportion of fish stocks within biologically sustainable levels)

- The article provides anecdotal but powerful evidence of declining stocks. Fisherman José Signorelli gives a specific example: “Three months ago, in two hours we would get 40 trays of scallops. Today, after five years, we got nothing.” This personal observation serves as a direct, albeit non-scientific, indicator of the health and sustainability of local scallop populations.

-

Income from artisanal fishing (Proxy for Indicator 8.5.1: Average hourly earnings)

- The article gives specific monetary values for the fishermen’s earnings, which can be used to measure their economic well-being. It states, “In times of abundance, two hours of diving can have you heading home with 100,000 pesos in your pocket. But on a bad day you can dive for five hours and not even make 50 pesos.” This data indicates both the potential income and its extreme volatility.

-

Number of people employed in the sector (Proxy for Indicator 8.5.2: Unemployment rate)

- The article provides concrete data on employment in artisanal fishing from the book “La pesca artesanal en Argentina.” It states there are “a total of 2,922 persons involved in artisanal sea-fishing in this country,” with “740” in the province of Chubut. This number serves as a baseline indicator for tracking employment in this specific sector.

-

Degree of institutional recognition for small-scale fisheries (Proxy for Indicator 14.b.1)

- The article implies this indicator by mentioning the existence of the “Puerto Madryn Artisanal Fishermen Association” since 1993 and the fact that their activity is formally permitted within a World Heritage protected area. This demonstrates a level of legal and institutional framework that recognizes and protects their access rights.

SDGs, Targets and Indicators

| SDGs | Targets | Indicators |

|---|---|---|

| SDG 14: Life Below Water | 14.4: End overfishing and destructive fishing practices.

14.b: Provide access for small-scale artisanal fishers to marine resources. |

Qualitative assessment of fish stocks: A fisherman’s observation of the dramatic decline in scallop catches over five years.

Institutional recognition: Artisanal fishing is the only extractive activity permitted within the World Heritage protected area. |

| SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth | 8.8: Protect labour rights and promote safe and secure working environments. | Income data: Specific earnings mentioned, from 100,000 pesos on a good day to less than 50 pesos on a bad day.

Employment data: The article cites a total of 2,922 people in artisanal fishing nationally, 740 in Chubut province. Working conditions: Mention of “almost zero social security, healthcare or pension payments.” |

| SDG 12: Responsible Consumption and Production | 12.2: Achieve the sustainable management and efficient use of natural resources. | Sustainable practices: The description of low-impact diving as an alternative to industrial methods and the fishermen’s principle of not “pillage the gulf” to ensure future “seeds to sow.” |

| SDG 1: No Poverty | 1.2: Reduce at least by half the proportion of men, women and children of all ages living in poverty. | Livelihood dependence: The article describes fishing as the primary economic activity for the community, with income figures directly linking their work to their financial survival. |

| SDG 17: Partnerships for the Goals | 17.17: Encourage and promote effective public, public-private and civil society partnerships. | Collaboration examples: The “joint work between scientists and fishermen” since the 1970s and the ongoing involvement of researchers like Ana Cinti. |

Source: batimes.com.ar

What is Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0