Promoting Resilient, Equitable, and Nutrition-Secure Food Systems in the Global South – orfonline.org

Report on Agrobiodiversity Loss and its Implications for the Sustainable Development Goals

Introduction: The Intersection of Agrobiodiversity and Sustainable Development Goals

The erosion of biodiversity, a foundational element for resilient food systems, presents a significant obstacle to achieving the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Modern agricultural practices, particularly intensive monoculture farming and the unsustainable use of natural resources, are accelerating this loss. The Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) reports approximately one million species are at risk of extinction, a crisis that directly undermines SDG 15 (Life on Land) and SDG 14 (Life Below Water). Agriculture is thus a primary driver of biodiversity loss, compromising the very ecological foundations necessary for long-term food production and threatening progress towards SDG 2 (Zero Hunger).

The promotion of agrobiodiversity is critical. Data from the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) indicates a dramatic narrowing of the global food base. Over 90 percent of crop varieties have vanished from farms, with just nine plant species constituting over two-thirds of global crop production. This homogenization of food sources jeopardizes nutritional diversity, a key component of SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being). The decline extends to wild relatives of domesticated species and marine stocks, further imperiling SDG 15 and SDG 14. The loss of non-food species essential for ecosystem services—such as pollinators and soil microorganisms—weakens the resilience of agricultural landscapes, impacting SDG 13 (Climate Action) by reducing the capacity of ecosystems to adapt to climate shocks.

This report analyzes the drivers of agrobiodiversity loss within the food systems of the Global South and proposes policy pathways to reconfigure production paradigms. These pathways are aligned with ecological sustainability and the broader Sustainable Development Goals, emphasizing principles that prioritize ecological balance and human well-being over unsustainable output growth, thereby supporting SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production).

Drivers of Agrobiodiversity Loss: A Challenge to the 2030 Agenda

In the Global South, which hosts numerous agrobiodiversity hotspots, the erosion of diverse farming systems is driven by systemic pressures that conflict with sustainable development principles. Dominant agricultural models, policy frameworks, and market structures favor intensification at the expense of ecological and social resilience.

Monocultures, Deforestation, and the Impact on SDG 15 and SDG 13

The expansion of monoculture-based agriculture is a primary driver of agrobiodiversity loss. Green Revolution paradigms promoted high-yielding varieties of staple crops, displacing diverse polycultures. This has led to significant genetic erosion, increasing vulnerability to pests and climate volatility, which directly challenges the targets of SDG 13 (Climate Action) and SDG 2 (Zero Hunger). Examples include:

- India: Over 75 percent of agricultural land is dedicated to rice and wheat, with a sharp decline in traditional, climate-resilient cereals like millets.

- Latin America: Conversion of biodiverse landscapes for soybean and cattle farming has degraded vital ecosystems.

- West Africa and Southeast Asia: Deforestation driven by cocoa and oil palm monocultures has resulted in significant forest loss, a direct setback for SDG 15 (Life on Land).

Agrochemical Overuse and its Threat to SDG 14 and SDG 15

The reliance on agrochemicals is intrinsically linked to monoculture expansion. Escalating fertilizer and pesticide use has severe consequences for biodiversity, undermining ecosystem health and contravening the principles of SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production).

- In India and China, excessive fertilizer use has led to soil nutrient imbalances and eutrophication of freshwater systems, harming aquatic biodiversity and impacting SDG 14 (Life Below Water).

- In Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America, intensified pesticide application has caused declines in pollinator populations and contaminated wetlands, further degrading ecosystems and threatening SDG 15.

Socio-Economic Consequences: Undermining SDG 1, SDG 2, SDG 5, and SDG 10

The erosion of agrobiodiversity has profound socio-economic impacts that hinder progress on multiple SDGs. The narrowing of food systems contributes to micronutrient deficiencies, affecting SDG 2 and SDG 3. For smallholder farmers and indigenous communities, who are custodians of a significant portion of the world’s remaining biodiversity, the loss of crop and livestock diversity threatens livelihoods and cultural heritage, working against SDG 1 (No Poverty) and SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities). These impacts are disproportionately borne by women, who are central to seed conservation and household nutrition. The marginalization of their role in governance structures undermines SDG 5 (Gender Equality).

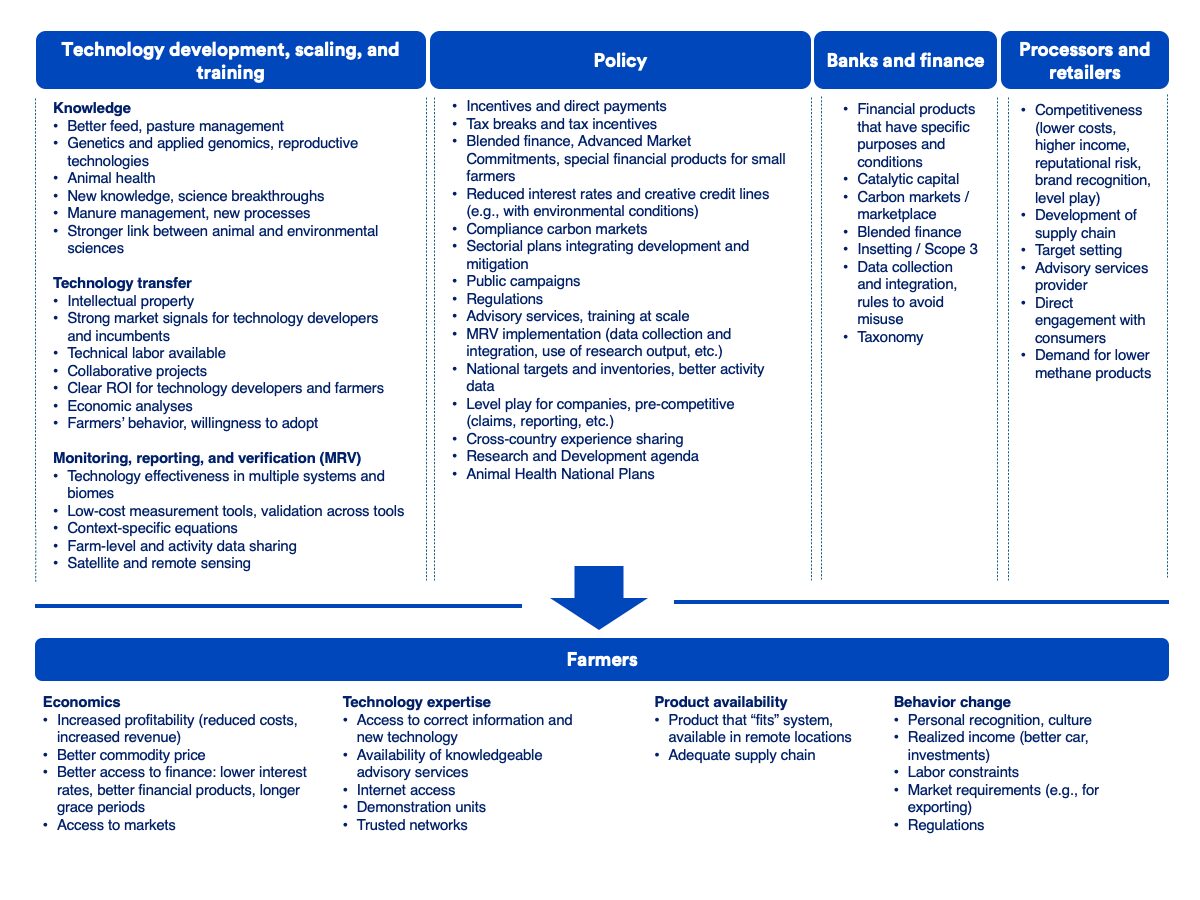

Policy Pathways for a Sustainable Transition Aligned with the SDGs

A paradigm shift towards diversified, ecologically grounded production systems is imperative for achieving the SDGs. The Global South can leverage agroecology, regenerative agriculture, and traditional knowledge to create pathways that balance productivity with ecological integrity.

Key Pathways for Agricultural Transition

- Agroecology and Regenerative Agriculture: These practices enhance biodiversity, improve soil health, and maintain yields, contributing to SDG 2, SDG 12, and SDG 15. Policy support should focus on farmer training, extension services, and realigning subsidies to support a transition away from chemical-intensive models.

- Agroforestry and Landscape-Based Approaches: Integrating trees into farming systems offers co-benefits for biodiversity conservation and food security, directly supporting SDG 13 and SDG 15. Integrated Landscape Management (ILM) models should be adapted to prioritize ecological limits and local food security over purely growth-oriented objectives.

- Diversified Cropping Systems and Seed Sovereignty: Reintegrating traditional and underutilized crops like millets into food systems enhances dietary diversity and climate resilience, advancing SDG 2 and SDG 3. Supporting community seed banks and participatory plant breeding empowers local communities, particularly women, strengthening seed sovereignty and contributing to SDG 5 and SDG 10.

- Traditional and Indigenous Knowledge Systems: Recognizing and integrating indigenous practices, such as community-based biodiversity management and rotational grazing, provides scalable models for sustainable agriculture. This validates local knowledge and supports the achievement of multiple SDGs by preserving cultural heritage and promoting ecological stewardship.

Institutional Levers for Accelerating SDG Progress

Scaling these alternative paradigms requires strong policy and institutional support. The following levers are critical for embedding biodiversity goals within national development strategies:

- Public Procurement and Subsidy Reform: Governments can create stable markets for biodiverse crops by integrating them into public food programs. Subsidies should be redirected from high-input monocultures to support agroecological practices, organic inputs, and water-efficient crops, aligning agricultural incentives with SDG 12.

- Reorientation of Research and Extension Services: Public investment in agricultural research must shift towards participatory breeding, community seed systems, and agroecological innovation. This bridges the gap between scientific and indigenous knowledge, fostering solutions tailored to local contexts.

- Cross-Sectoral Collaboration: Achieving systemic change requires collaboration between ministries of agriculture, environment, and health. This ensures that biodiversity conservation is integrated into food security, public health, and climate adaptation strategies, creating policy coherence in support of the 2030 Agenda.

- Mainstreaming Equity and Nutrition: Biodiversity strategies must be equity-sensitive, amplifying the voices and roles of women, smallholders, and indigenous communities. Incorporating nutrient-rich, diverse foods into national dietary guidelines and social safety nets will advance SDG 2, SDG 3, and SDG 5.

Conclusion: Centering Biodiversity for a Resilient and Equitable Future

Safeguarding biodiversity is a central prerequisite for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. The current trajectory of agrobiodiversity loss, driven by industrial agriculture, undermines ecological resilience, food and nutrition security, and social equity. A systemic transformation is required to embed biodiversity conservation into the architecture of agricultural policy and governance. By realigning policies, redirecting investments, and championing inclusive governance, nations in the Global South can transition from extractive models to biodiversity-centered paradigms. Such a reorientation is essential for building climate-resilient food systems and securing the ecological and cultural foundations necessary for a sustainable future for all.

Analysis of Sustainable Development Goals in the Article

1. Which SDGs are addressed or connected to the issues highlighted in the article?

-

SDG 2: Zero Hunger

- The article directly addresses food security by discussing how biodiversity loss undermines the “ecological foundations” of agriculture. It highlights the narrowing of the food base, with “just nine plant species” accounting for “more than 66 percent of global crop production,” which increases vulnerability.

- It discusses the impact of dietary homogenization on nutrition, leading to “micronutrient deficiencies” in regions like South Asia, which is a core component of achieving zero hunger.

- The promotion of “diversified, ecologically grounded production systems” such as agroecology and the revival of traditional crops like millets are presented as solutions to ensure long-term, sustainable food production.

-

SDG 5: Gender Equality

- The article explicitly points out the gendered impacts of agrobiodiversity loss. It states that “women, who play key roles in seed management, household nutrition, and agroecological practices, are disproportionately affected when genetic resources are lost.”

- It highlights the systemic undervaluation of women’s contributions, noting that in Sub-Saharan Africa, women are responsible for “60–80 percent of food production, yet their contributions are systematically undervalued,” and they “often lack secure land tenure and access to credit.”

-

SDG 12: Responsible Consumption and Production

- The article critiques the unsustainable production patterns of modern agriculture, particularly the “escalating reliance on agrochemicals.” It provides data on the massive increase in fertilizer consumption in India and China and pesticide use in Latin America.

- It discusses the environmental consequences of these production methods, such as “severe soil nutrient imbalances,” “widespread eutrophication of freshwater systems,” and contamination of wetlands, directly linking agricultural production to environmental degradation.

-

SDG 14: Life Below Water

- The article connects land-based agricultural practices to the health of aquatic ecosystems. It mentions that overuse of nitrogen fertilizer in China has resulted in “widespread eutrophication of freshwater systems and losses in aquatic biodiversity.”

- It directly addresses marine biodiversity by stating that “Overfishing has affected approximately one-third of marine stocks,” and a similar proportion of freshwater species face extinction risks.

-

SDG 15: Life on Land

- This is a central theme of the article. It begins by stating that biodiversity is “being eroded at an alarming rate by modern agricultural practices” and that “around one million species are currently at risk of extinction.”

- It provides specific examples of habitat destruction and deforestation driven by agriculture, such as “soy-driven agricultural expansion” in Brazil, “cocoa-driven deforestation in Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana,” and the proliferation of “oil palm monocultures” in Indonesia.

- The article also discusses the decline of crucial non-food species like pollinators, invertebrates, and soil micro-organisms, which are vital for terrestrial ecosystem functioning.

2. What specific targets under those SDGs can be identified based on the article’s content?

-

Target 2.4: Sustainable food production and resilient agricultural practices

- The article’s entire argument is a critique of current agricultural practices (monoculture, high-input) for being unsustainable and a call to shift towards “diversified, ecologically grounded production systems” like agroecology, regenerative agriculture, and agroforestry, which are resilient alternatives.

-

Target 2.5: Maintain genetic diversity of seeds, plants, and animals

- The article directly addresses this target by stating that “over 90 percent of crop varieties have disappeared from farmers’ fields” and that the “genetic diversity of wild relatives of domesticated species is diminishing.” It promotes solutions like “community seed banks” and “participatory plant breeding programmes” to maintain this diversity.

-

Target 5.a: Give women equal rights to economic resources and land

- The article implies a need to work towards this target by highlighting that women in the Global South, despite being central to food production and biodiversity conservation, “often lack secure land tenure and access to credit,” and their contributions are marginalized by existing governance structures.

-

Target 12.4: Responsible management of chemicals and waste

- This target is identified through the article’s detailed section on “Agrochemical Overuse,” which describes how the expansion of monocultures is “inseparable from the escalating reliance on agrochemicals.” It provides specific examples of increased fertilizer and pesticide use in India, China, and Latin America, leading to severe environmental damage.

-

Target 14.1: Reduce marine pollution

- The article connects to this target by describing how nitrogen fertilizer runoff from agriculture in China has resulted in “widespread eutrophication of freshwater systems,” a form of nutrient pollution originating from land-based activities that harms aquatic ecosystems.

-

Target 14.4: End overfishing and restore fish stocks

- The article directly references this target by stating, “Overfishing has affected approximately one-third of marine stocks.”

-

Target 15.2: Halt deforestation

- The article provides concrete examples of deforestation linked to agricultural expansion, which directly relates to this target. It cites “cocoa-driven deforestation in Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana,” soy monocultures in Brazil’s Cerrado, and oil palm expansion in Indonesia, which “accounted for 23 percent of the deforestation” in the country between 2001 and 2016.

-

Target 15.5: Protect biodiversity and prevent extinctions

- This target is central to the article’s introduction, which cites the IPBES estimate that “around one million species are currently at risk of extinction.” It also notes that “nearly 20 percent of food-relevant wild species” are threatened on the IUCN Red List and that “one-third of freshwater species face extinction risks.”

3. Are there any indicators mentioned or implied in the article that can be used to measure progress towards the identified targets?

-

Number/Proportion of threatened species

- The article explicitly mentions several figures that can be used as indicators: “around one million species are currently at risk of extinction,” “nearly 20 percent of food-relevant wild species sourced as human food marked as threatened on the International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List,” and “one-third of freshwater species face extinction risks.” These align with measuring progress on Target 15.5.

-

Rate of loss of crop and livestock genetic diversity

- The statement that “over 90 percent of crop varieties have disappeared from farmers’ fields” serves as a stark indicator of the loss of genetic diversity, relevant to Target 2.5. The dominance of just nine plant species in global crop production is another measurable indicator of this trend.

-

Proportion of fish stocks within biologically sustainable levels

- The article provides a direct indicator for Target 14.4 by stating that “approximately one-third of marine stocks” have been affected by overfishing, implying they are outside sustainable levels.

-

Rate of deforestation

- The article provides specific data points that serve as indicators for Target 15.2. For example, it mentions that oil palm expansion in Indonesia led to “roughly 840,000 hectares of primary forest lost annually” and that cocoa cultivation has resulted in “over 37 percent and 13 percent forest loss, respectively, within protected areas” in Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana.

-

Volume of fertilizer and pesticide use

- To measure progress on Target 12.4, the article provides quantifiable trends. It notes that in India, “fertiliser consumption rose from less than 1 million tonnes in the early 1960s to nearly 30 million tonnes by 2019,” and in Latin America, “pesticide use has increased by 190 percent since 1990.”

Table of SDGs, Targets, and Indicators

| SDGs | Targets | Indicators |

|---|---|---|

| SDG 2: Zero Hunger | 2.4: Ensure sustainable food production systems and implement resilient agricultural practices.

2.5: Maintain the genetic diversity of seeds, cultivated plants and farmed and domesticated animals. |

|

| SDG 5: Gender Equality | 5.a: Undertake reforms to give women equal rights to economic resources, as well as access to ownership and control over land. |

|

| SDG 12: Responsible Consumption and Production | 12.4: Achieve the environmentally sound management of chemicals and all wastes throughout their life cycle. |

|

| SDG 14: Life Below Water | 14.1: Prevent and significantly reduce marine pollution of all kinds, in particular from land-based activities.

14.4: Effectively regulate harvesting and end overfishing. |

|

| SDG 15: Life on Land | 15.2: Promote the implementation of sustainable management of all types of forests, halt deforestation.

15.5: Take urgent and significant action to… halt the loss of biodiversity and… prevent the extinction of threatened species. |

|

Source: orfonline.org

What is Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0