Do countries have a duty to prevent climate harm? The world’s highest court is about to answer this crucial question – The Conversation

Report on the International Court of Justice Advisory Opinion on Climate Change Obligations and the Sustainable Development Goals

Introduction: A Landmark Opinion for Global Climate Action

The International Court of Justice (ICJ) is set to deliver a significant advisory opinion clarifying the obligations of states concerning climate change. This judicial clarification directly addresses the core tenets of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, particularly SDG 13 (Climate Action), which calls for urgent measures to combat climate change and its impacts. The request for this opinion, initiated by the climate-vulnerable nation of Vanuatu and co-sponsored by 132 states, exemplifies SDG 17 (Partnerships for the Goals) and underscores the growing demand for accountability and justice under SDG 16 (Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions).

While not legally binding, the opinion from the world’s highest court is expected to be highly persuasive, providing an authoritative interpretation of international law that will influence national policies and legal frameworks aimed at achieving the SDGs.

Core Mandate of the Advisory Opinion

The ICJ has been tasked with answering two fundamental questions that are critical to the enforcement of global climate commitments:

- What are the obligations of States under international law to ensure the protection of the climate system and other parts of the environment from anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions for States and for present and future generations?

- What are the legal consequences under these obligations for States where they, by their acts and omissions, have caused significant harm to the climate system and other parts of the environment?

Key Areas of Deliberation and SDG Linkages

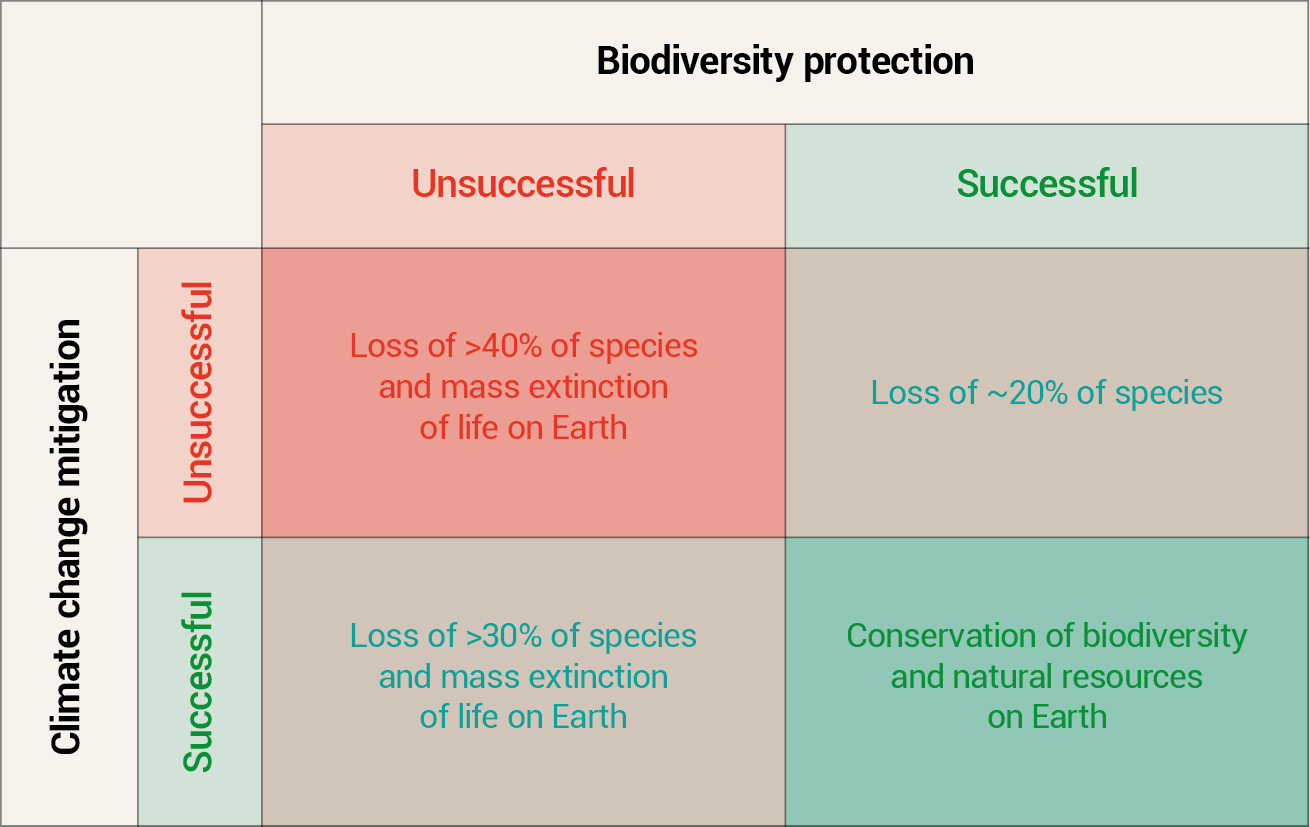

- Integrated Legal Framework: The ICJ is expected to conduct an encyclopaedic examination of international law, extending beyond climate treaties to include human rights, trans-boundary environmental law, and trade law. This integrated approach mirrors the indivisible nature of the SDGs, where climate action (SDG 13) is intrinsically linked to good health (SDG 3), sustainable economic growth (SDG 8), and the protection of terrestrial and marine ecosystems (SDG 14 and SDG 15).

- Intergenerational Equity: The opinion will explicitly address state obligations to future generations. This aligns with the foundational principle of the SDGs to create a sustainable world for all, ensuring that the needs of the present are met without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.

- Accountability and Consequences: By addressing the legal consequences for states causing significant environmental harm, the opinion aims to strengthen mechanisms for accountability. This is vital for the successful implementation of SDG 13 and reinforces the role of international law in upholding SDG 16 by ensuring justice for climate-related damages.

Global Judicial Context and Implications for SDG 16

Comparative Judicial Approaches

Recent rulings from other high courts provide a potential framework for the ICJ’s findings:

- Inter-American Court of Human Rights: This court’s advisory opinion affirmed that protecting the ecosystem is a fundamental principle of international law, explicitly linking a healthy environment to human rights. This approach strengthens the legal basis for climate action as a prerequisite for achieving SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being).

- Australian Federal Court: In contrast, a recent Australian ruling determined that the government does not owe a common law duty of care to protect citizens from climate change consequences, citing “high government policy.” This highlights a significant challenge in translating international climate goals into domestic legal obligations, potentially impeding progress on SDG 13 at the national level.

The ICJ’s opinion has the potential to provide a clear, global judicial direction, encouraging a more harmonized approach to climate litigation and policy that supports the entire 2030 Agenda.

Case Study: New Zealand’s Climate Policy and SDG Alignment

An Assessment of National Commitments

New Zealand’s climate policies present a mixed record when evaluated against the Sustainable Development Goals. While the Climate Change Response (Zero Carbon) Amendment Act 2019 sets ambitious targets, current actions appear insufficient to meet them, revealing inconsistencies in the nation’s commitment to the SDGs.

Policy Contradictions and Challenges

- Inadequate Progress on SDG 13: Despite legislative targets, rising transport emissions and lightly regulated agricultural emissions indicate that New Zealand is struggling to meet its commitments under SDG 13 (Climate Action).

- Conflicts with SDG 7 and SDG 11: The government’s decision to lift a ban on offshore gas exploration and co-invest in new fields directly conflicts with the objectives of SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy). Furthermore, slow progress on installing EV charging stations and the termination of a clean-investment fund undermine efforts toward SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities).

- Potential for Increased Scrutiny: A strong ICJ opinion affirming binding state obligations to prevent climate harm could expose New Zealand’s policies to increased legal and international pressure. It may compel the government to enhance the ambition of its Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) under the Paris Agreement and better align its domestic agenda with its international commitments to the SDGs.

1. Which SDGs are addressed or connected to the issues highlighted in the article?

SDG 13: Climate Action

- The entire article is centered on climate change, discussing the “obligations of states under international law to protect the climate and environment from greenhouse gas emissions” and the “legal consequences for states that have caused significant harm.” It directly addresses the need for urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts.

SDG 16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions

- The article focuses on the role of the International Court of Justice (ICJ), the “world’s highest court,” in clarifying international law on climate change. This relates to building effective, accountable, and inclusive institutions at the international level. The discussion of “legal consequences,” “state obligations,” and domestic court cases like the one involving Torres Strait Islanders highlights the theme of access to justice and the rule of law.

SDG 17: Partnerships for the Goals

- The initiative for the ICJ advisory opinion is described as a major international collaboration, “led by Vanuatu and co-sponsored by 132 member states, including New Zealand and Australia.” This exemplifies a global partnership for sustainable development, initiated by a developing nation and supported by a broad coalition of countries.

SDG 7: Affordable and Clean Energy

- The article discusses New Zealand’s energy policies as part of its climate response. It mentions the government’s plan to “double renewable energy by 2050” but also its actions to lift a “ban on offshore gas exploration” and axe a “clean-investment fund.” This directly connects to the transition towards clean energy.

SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities

- The article touches upon sustainable transport systems, a key component of sustainable communities. It notes that in New Zealand, “Transport emissions continue to rise” and mentions the government’s promise to install “10,000 EV charging stations by 2030” as a measure to address this.

2. What specific targets under those SDGs can be identified based on the article’s content?

SDG 13: Climate Action

- Target 13.1: Strengthen resilience and adaptive capacity to climate-related hazards and natural disasters in all countries. This is highlighted by the mention of Vanuatu, described as “one of the most vulnerable nations to climate-related impacts,” and the Torres Strait Islanders who “face significant loss and damage from climate impacts.”

- Target 13.2: Integrate climate change measures into national policies, strategies and planning. The article extensively discusses national policies, such as New Zealand’s “Climate Change Response (Zero Carbon) Amendment Act 2019,” its emissions reduction targets, and the submission of “nationally determined contributions) under the Paris Agreement.”

- Target 13.3: Improve education, awareness-raising and human and institutional capacity on climate change mitigation, adaptation, impact reduction and early warning. The campaign that began with “students and youth organisations in Vanuatu” persuading their government is a direct example of awareness-raising and civil society action leading to institutional change.

SDG 16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions

- Target 16.3: Promote the rule of law at the national and international levels and ensure equal access to justice for all. The request for an ICJ advisory opinion is an effort to clarify and promote the “rule of law” at the international level regarding climate obligations. The Australian federal court case involving Torres Strait Islanders is an example of seeking access to justice for climate-related harm.

- Target 16.8: Broaden and strengthen the participation of developing countries in the institutions of global governance. The article shows this target in action, as the campaign was “led by Vanuatu,” a small island developing state, which successfully brought the issue to the United Nations General Assembly and the ICJ.

SDG 17: Partnerships for the Goals

- Target 17.16: Enhance the global partnership for sustainable development, complemented by multi-stakeholder partnerships. The effort is described as being “co-sponsored by 132 member states,” demonstrating a large-scale global partnership to achieve a common goal.

SDG 7: Affordable and Clean Energy

- Target 7.2: By 2030, increase substantially the share of renewable energy in the global energy mix. This is directly referenced in New Zealand’s plan to “double renewable energy by 2050.”

- Target 7.a: By 2030, enhance international cooperation to facilitate access to clean energy research and technology… and promote investment in energy infrastructure and clean energy technology. The article mentions New Zealand’s promise to install “10,000 EV charging stations by 2030” and the axing of a “clean-investment fund,” both of which relate to investment in clean energy infrastructure.

3. Are there any indicators mentioned or implied in the article that can be used to measure progress towards the identified targets?

Indicators for SDG 13

- Indicator 13.2.1 (Number of countries with nationally determined contributions (NDCs)): The article explicitly mentions that “Most countries have yet to submit their latest emissions reduction pledges (known as nationally determined contributions) under the Paris Agreement.” This is a direct reference to this official indicator.

- Implied Indicator (Greenhouse Gas Emissions): The article provides specific figures and trends for emissions, such as New Zealand’s targets to reduce “long-lived greenhouse gases (carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide) to net zero, and biogenic methane by 25-47%” and the fact that its “Transport emissions continue to rise.”

Indicators for SDG 7

- Implied Indicator (Share of renewable energy): Progress can be measured by tracking the goal to “double renewable energy by 2050.”

- Implied Indicator (Investment in clean energy infrastructure): The promise to install “10,000 EV charging stations by 2030” serves as a measurable indicator of investment in sustainable transport infrastructure. The status of the “$200 million to co-invest in the development of new [gas] fields” versus the axing of a “clean-investment fund” are also indicators of investment direction.

Indicators for SDG 17

- Implied Indicator (Number of countries in global partnerships): The article provides a clear metric for the partnership by stating it was “co-sponsored by 132 member states.”

4. Table of SDGs, Targets, and Indicators

| SDGs | Targets | Indicators Identified in the Article |

|---|---|---|

| SDG 13: Climate Action | 13.1: Strengthen resilience and adaptive capacity. 13.2: Integrate climate measures into national policies. 13.3: Improve education and awareness-raising. |

– Submission of Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). – National emissions reduction targets (e.g., net-zero for CO2, 25-47% for methane). – Trends in sectoral emissions (e.g., rising transport emissions). |

| SDG 16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions | 16.3: Promote the rule of law and ensure equal access to justice. 16.8: Broaden participation of developing countries in global governance. |

– Use of international legal bodies like the ICJ to clarify state obligations. – Leadership role of developing nations (Vanuatu) in UN processes. |

| SDG 17: Partnerships for the Goals | 17.16: Enhance the global partnership for sustainable development. | – Number of countries co-sponsoring the UN resolution (132 member states). |

| SDG 7: Affordable and Clean Energy | 7.2: Increase the share of renewable energy. 7.a: Promote investment in clean energy infrastructure. |

– National goals for renewable energy (e.g., double by 2050). – Number of EV charging stations to be installed (10,000 by 2030). – Status of clean energy investment funds. |

| SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities | 11.2: Provide access to sustainable transport systems. | – Data on transport emissions trends. – Infrastructure targets for sustainable transport (e.g., EV chargers). |

Source: theconversation.com

What is Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0