Explainer: What is offshore wind and what does its future look like?

Offshore wind farms are making waves globally, with their capacity set to increase tenfold by 2030 and over $1 trillion expected to be invested in the industry. These projects help countries reduce their dependence on fossil fuels, expedite the journey to net-zero emissions, and generate economic growth and jobs. Floating wind farms, in particular, are gaining prominence for their potential to harness wind energy in deep waters, though challenges remain, especially regarding investments and infrastructure. These developments are pivotal in the transition to a more sustainable and cleaner energy future.

Explainer: What is offshore wind and what does its future

look like?

Energy Transition

- Offshore wind farms are hitting the headlines for their size and for gaining government backing across the globe.

- Boosting offshore wind power is seen as a way to reduce reliance on fossil fuels and speed the journey to net zero, and it can also create jobs and economic growth.

- There are still challenges to overcome to scale the technology, especially for floating offshore wind, which is not yet industrialized.

Picture a plate of cupcakes. Look tempting don’t they? But each one took energy to bake - energy that could in future be generated by offshore wind farms.

In fact, just one rotation of a GE Haliade-X 12 MW offshore wind turbine generates enough power to bake 28 plates full of cupcakes or, perhaps more usefully, power the average UK home for 24 hours.

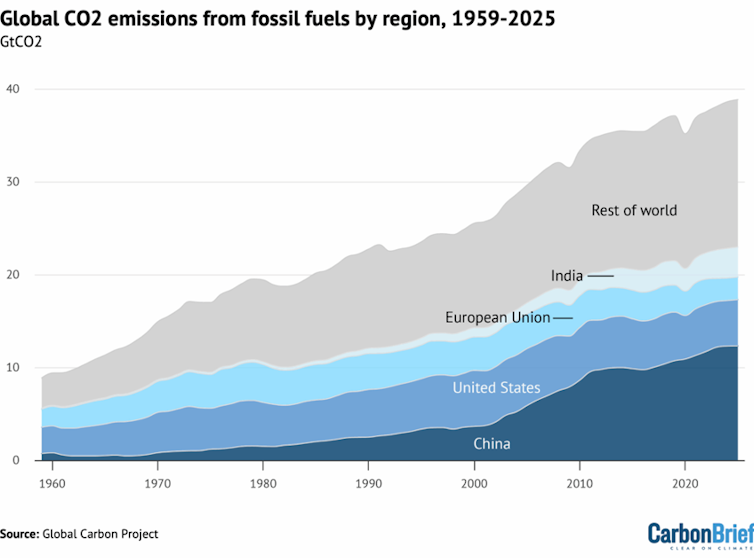

Offshore wind farms are hitting the headlines across the globe for their sheer scale - and as countries increasingly turn to them to decrease their dependency on energy from Russia as well as speed up their energy transition.

Global capacity of large-scale wind farms is expected to increase 10-fold, from 34 GW in 2020 to 330 GW in 2030, and spread throughout 24 countries (up from nine today), according to a report by consultancy Wood McKenzie. It estimated $1 trillion would flow into the offshore wind industry over the next decade.

Winds of change around the globe

Kincardine, off the coast of Scotland, is currently the world’s largest floating wind farm, with five giant V164-9.525 MW turbines made by Danish company Vestas.

In August, eight EU countries on the Baltic Sea pledged to increase offshore wind power generation capacity sevenfold by 2030, up from 2.8 GW currently, most of which is in Danish and German waters.

Putting further wind in the sails of the renewables sector, the Biden administration in the US unveiled its Floating Offshore Wind Shot in September. It aims to “reduce the costs of floating technologies by more than 70% by 2035, to $45 per megawatt-hour” and increase capacity to 15 GW by 2035, enough to power 5 million homes.

This is in addition to the 30 GW by 2030 of offshore wind power target, which will be mainly met through ‘fixed-bottom’ technology.

How is the World Economic Forum facilitating the transition to clean energy?

The southern Chinese city of Chaozhou is planning a wind farm that would dwarf all of Norway’s power plants combined, according to Bloomberg. The International Energy Agency (IEA) expects China to have the largest installed offshore wind capacity by the end of 2022 - more than the UK and EU combined.

Boosting offshore wind power is seen as a way to reduce reliance on fossil fuels and speed the journey to net zero. But it’s also providing jobs and economic growth to coastal towns and revitalizing industries, with the Global Wind Energy Council in 2021 predicting both onshore and offshore wind would create 3.3 million jobs over the next five years across the entire value chain.

But what exactly are offshore wind farms and what does the future hold?

Offshore wind farms: floating vs fixed bottom

Kincardine might be the world’s largest floating windfarm, but Hornsea 2, off the coast of Yorkshire in the UK, is the world’s largest fixed-bottom offshore wind farm and became fully operational in September.

Run by Danish energy company Ørsted, which pioneered the first offshore wind farms 30 years ago, Hornsea 2’s 165 wind turbines are sited next to its older sibling Hornsea 1 - and together they can power 2.5 million homes, contributing to the UK government’s goal of 50 GW in offshore wind capacity by 2030.

In July, Ørsted were awarded the contract for Hornsea 3, which will power 3.2 million homes, while Hornsea 4 is going through the planning process and a decision is expected in early 2023.

It’s hard to imagine how colossal these feats of engineering are. The giant blades on Vestas’ V164 turbines are each 80 metres long, for example, and when they’re installed on towers, the tip of the blade can reach more than 200m above sea level - that’s more than twice as tall as the Statue of Liberty.

Then there are the 390km of subsea export cables that take the power generated from Hornsea 2 to the shore at Horseshoe Point in Lincolnshire.

So what’s the difference between floating and fixed-bottom wind farms?

It comes down to location. Floating wind turbines don’t need to be grounded in the seabed, like fixed-bottom ones, so they can be sited further out to sea in water deeper than 60m, where winds are stronger. They are then anchored to the seabed with multiple mooring lines, borrowing technology from floating oil platforms, according to the Norwegian state-owned energy firm Equinor.

Is the future floating?

If onshore wind was the first generation in wind-farm technology, which informed offshore fixed-bottom wind farms, floating wind farms are effectively the third generation.

“Floating offshore wind will be able to build on the developments made in seabed fixed offshore wind to reach scale even faster – much as today’s offshore wind industry was built on achievements onshore,” says Gabriel Davies, Ørsted’s Programme Director, Floating Wind.

As of October 2022, only around 50 floating offshore wind turbines have been commissioned, says Davies. But global stock is expected to exceed 5 GW by 2030 and 25 GW by 2035.

While fixed-bottom wind farms cost less to install, the real potential for power generation is floating on the horizon. The IEA found, in 2019 the potential for offshore wind power globally could be 18 times the current global power demand - with the majority where waters are deeper than 60m and better suited to floating turbines.

To scale, companies are working together to create a global offshore wind ecosystem - for example, UK company Principle Power created the floating structure for Kincardine, and the turbines themselves were made by Danish firm Vestas.

To ensure the turbines can withstand North Sea storms, a mechanism of pumps shifts liquid ballast between the floating yellow cylinders which balances the platform and puts the turbine at the best angle, Principle Power’s Greg Campbell-Smith told the BBC.

What are the challenges in building offshore wind farms?

Investment and government backing is crucial to ensure capacity grows in a sustainable way. But with growing competition for projects that take years to complete, require local ‘content’ when the local industry may still be in its infancy, as well as access to deep sea ports, wind turbine installation vessels and other essential infrastructure, uncertainty can creep in.

“With all the political ambition going into this space, in the North Sea, and the Baltic Sea, in the US, building up capacity in the industry to actually deliver in a cost-effective way is very important,” says Nils Askær-Hune, Ørsted’s Lead Public Affairs Advisor on Socio-Economics, Global Public Affairs.

“We have to have a long horizon for planning. In order to ensure efficient resource utilization, it is essential that the expansion takes place sequentially and is planned in accordance with the expansion of capacity in the industry.”

The current auction process is precarious, with some governments using ‘zero bid’ auctions and toying with the concept of ‘negative bidding’, which would see wind companies paying them for the right to develop, according to Wind Europe.

Added to the rise in transport and materials costs due to COVID-19 and compounded by the energy crisis and war in Ukraine, it’s becoming harder to build viable projects with sustainable supply chains.

Decarbonizing the wind-farm value chain is also a major challenge, as the turbines themselves are made from steel and other metals which require energy-intensive processes to manufacture.

Askær-Hune says: “We can build offshore wind farms which will help reduce global greenhouse gas emissions as they produce green energy and enable the production of green hydrogen that enables the decarbonization of hard-to-abate sectors. However, in order to create a world that runs entirely on green energy, as a company we must decarbonize our full value chain. At Ørsted we work every day to achieve net-zero emissions in our full value chain (scope 1-3) by 2040.”

Another challenge is around the impact of an offshore wind farm on marine biodiversity. Ørsted aims to have a net-positive impact on biodiversity by design, such as turning the foundations of fixed-bottom turbines into artificial reefs - habitats and shelter for species like mussels, Atlantic cod and even coral.

For example, the company has just launched a global partnership with WWF to advance offshore wind deployment that enhances ocean biodiversity.

Floating wind turbines can be installed with less noise and disruption to marine mammals and beyond the foraging ranges of breeding birds, says Ørsted. But the anchors and mooring lines will need monitoring for their impacts on life on the seafloor.

What governments can do to support offshore wind farms

The ambition and will for wind is there, but bureaucracy around permits is slowing down the process.

At COP27, nine new countries joined the Global Offshore Wind Alliance initiated by the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), Denmark and the Global Wind Energy Council, which wants to "lift the barriers" to developing offshore wind.

Meanwhile, the European Commission has proposed temporary new emergency regulation designed to speed up the REPowerEU Plan to develop renewables to accelerate the energy transition and end the EU’s dependence on Russian gas.

Specifically, this would help to fast-track lengthy and complicated administrative and permitting procedures stopping the development of renewables projects.

As Vestas notes in this Economist article: “The climate and energy crises are hugely complex, but the solutions are available. By accelerating the permitting process governments will not only ensure their energy security and reduce emissions, but also unlock swathes of economic potential. The time to act is now.”

Both Ørsted and Vestas are members of the World Economic Forum’s First Movers Coalition of companies creating a market for the emerging technologies that are crucial in order to reach Net Zero by 2050.

What is Your Reaction?

Like

2

Like

2

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0