Genital examinations in cases of suspected ‘female genital mutilation’ in Sweden 1982–2022: lawful decisions resulting in structural injustice – Nature

Report on the Investigation of ‘Female Genital Mutilation’ in Sweden: An Analysis of Lawful Decisions and Structural Injustice in the Context of Sustainable Development Goals

Abstract

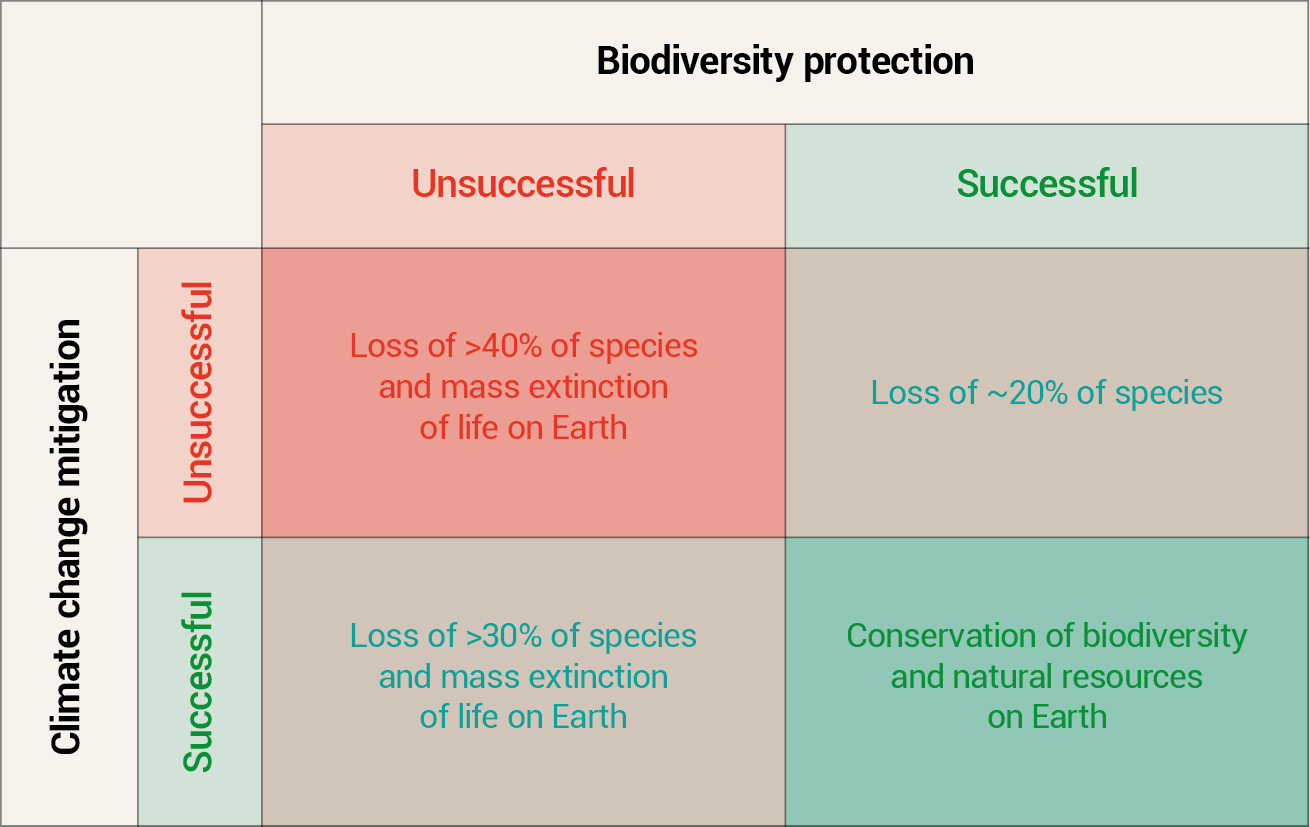

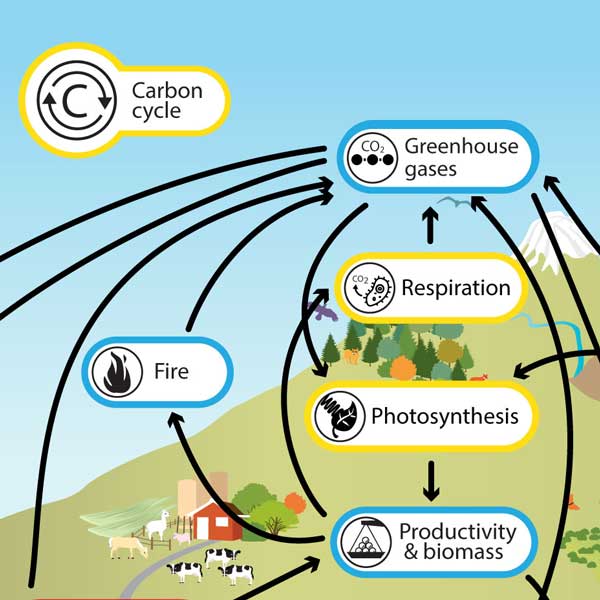

This report critically examines the implementation of Sweden’s legal and policy measures for detecting and prosecuting ‘female genital mutilation’ (FGM) within immigrant communities. The analysis, based on police case files and professional interviews, reveals a significant disconnect between state actions and outcomes. Despite numerous investigations centered on forced genital examinations, no prosecutions have resulted from this specific measure. This finding raises critical questions about the proportionality of current strategies and their alignment with key Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 5 (Gender Equality), SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities), and SDG 16 (Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions). The report argues that Sweden’s reliance on invasive, suspicion-based measures contributes to structural injustice by over-policing and marginalizing specific communities. This approach overlooks significant cultural shifts in attitudes toward the practice post-migration. A re-evaluation of current strategies is necessary to ensure interventions are proportionate, rights-based, and build trust, thereby effectively protecting children while upholding principles of justice and equality.

1. Introduction: FGM in the Context of Sustainable Development Goals

Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) is a harmful practice recognized as a violation of human rights and a significant barrier to achieving several Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). This report analyzes Sweden’s approach to combating FGM, focusing on the unintended consequences of its legal and investigative frameworks.

1.1. Alignment with SDG 5: Gender Equality

Sweden’s legislative actions against FGM, initiated in 1982, directly support SDG 5 (Gender Equality), specifically Target 5.3, which calls for the elimination of all harmful practices, including FGM. The country has strengthened its legal framework over decades, removing the principle of double criminality in 1999 and introducing travel bans in 2020 to prevent potential cases. These measures, alongside educational campaigns, demonstrate a strong commitment to protecting the bodily integrity and rights of women and girls.

1.2. Challenges to SDG 10 and SDG 16

Despite these intentions, the implementation of these laws has raised concerns related to SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities) and SDG 16 (Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions). Investigative practices, particularly the use of forced genital examinations on children from immigrant communities, appear disproportionate to the number of actual prosecutions. This pattern of over-policing risks creating structural injustice, where state actions, though legally sanctioned, systematically disadvantage and stigmatize specific ethnic groups. This report examines whether these practices undermine the goal of building effective, accountable, and inclusive institutions (Target 16.6) and ensuring non-discriminatory laws and policies (Target 16.b).

2. Theoretical Framework: Proportionality and Structural Injustice

2.1. The Principle of Proportionality

The principle of proportionality, codified in Swedish law, requires that state interventions must be necessary, balanced, and the least intrusive means to achieve a legitimate aim. In the context of FGM investigations, this involves weighing the objective of protecting children against the infringement on individual rights, such as:

- The right to bodily integrity.

- The right to respect for private and family life (Article 8, ECHR).

- Protection against discrimination (Article 14, ECHR).

This report assesses whether the measures employed by Swedish authorities, particularly forced genital examinations, adhere to this principle.

2.2. Structural Injustice and Its Impact on SDGs

Drawing on Iris Marion Young’s theory, this report analyzes how well-intentioned systems can produce structural injustice. This occurs when institutional norms and processes systematically disadvantage certain groups, even without overt discriminatory intent. In this context, over-policing based on perceived cultural practices rather than objective evidence can:

- Exacerbate the marginalization of immigrant communities, undermining SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities).

- Erode trust between communities and state institutions, hindering the collaborative partnerships needed to achieve SDG 5 (Gender Equality) and SDG 16 (Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions).

- Create a system where lawful actions result in discriminatory outcomes, perpetuating cycles of suspicion and social exclusion.

3. Findings: Analysis of Investigative Practices and Outcomes (1996-2022)

An analysis of 230 police case files from 1996 to 2022 reveals a significant disparity between the scale of investigation and the number of prosecutions. The findings challenge the assumption that a high number of clandestine FGM cases are evading authorities and instead point to a pattern of over-enforcement.

3.1. Overview of Criminal Investigations

The data from the case file archive indicates the following outcomes:

- Total Cases Analyzed: 179 relevant police investigations.

- Cases with Genital Examinations: 101 investigations included genital examinations of girls.

- Outcome of Examinations:

- 76 cases (75%): No signs of FGM were found. Investigations were closed.

- 25 cases (25%): Traces of FGM were found.

- Prosecutions:

- Of the 25 cases where FGM was indicated, 23 were closed without prosecution, typically because the act occurred before migration to Sweden.

- Only three FGM-related cases have ever reached a Swedish criminal court, all involving procedures performed in African countries and reported by the girls themselves.

- Crucially, not a single prosecution has resulted from an investigation initiated by a forced genital examination.

3.2. The Role of Coercive Measures

The primary investigative tool is the genital examination, often conducted without parental consent via a court-appointed special representative. This practice has significant implications for multiple SDGs.

3.2.1. Impact on SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being)

The invasive nature of forced examinations, often performed on young children without adequate emotional support, poses a direct risk to their psychological and emotional well-being. Cases reveal that children have been subjected to:

- Multiple examinations due to a lack of specialized medical expertise.

- Examinations despite their explicit objections.

- Separation from parents and familiar environments, causing significant distress.

These interventions, intended to protect health, may themselves inflict trauma, undermining the principles of SDG 3.

3.2.2. Impact on SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities) and SDG 16 (Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions)

Investigations are disproportionately triggered by vague suspicions against families from specific ethnic backgrounds. Reports from preschool staff about “unusual” genital appearance have led to full-scale criminal investigations that ultimately found no evidence of FGM. This targeting of “suspect communities” constitutes a form of structural discrimination, which is antithetical to the goals of SDG 10 and SDG 16. It erodes trust and reinforces a sense of exclusion and racial profiling among affected communities.

4. Discussion: The Disconnect Between Policy and Reality

4.1. Overlooking Cultural Change

Swedish policy appears to operate on the assumption that FGM is widely practiced clandestinely among immigrant communities. However, extensive research indicates a significant cultural shift, with migration providing an opportunity for families to abandon the practice. The low number of court cases is more likely a reflection of this cultural transformation than a failure of law enforcement. By ignoring this evidence, current policies fail to engage with communities as partners, instead treating them with suspicion. This approach is counterproductive to achieving the long-term, sustainable behavioral change envisioned by SDG 5.

4.2. The Ripple Effect of Structural Injustice

The current system, where professionals diligently follow guidelines, creates a cumulative effect of structural injustice. Each step—from a mandatory report by a preschool teacher to a police investigation and a forced examination—is legally sound in isolation. However, the collective result is a disproportionate and harmful burden on a specific demographic. This process undermines the core principles of SDG 16 by failing to ensure that justice is administered equitably and that institutions are sensitive to the diverse populations they serve.

5. Recommendations for an SDG-Aligned Approach

To better align Sweden’s efforts with the Sustainable Development Goals and ensure that child protection measures are both effective and just, this report proposes the following recommendations:

- Enhance Professional Training: Move beyond awareness campaigns like ‘Dare to See’. Training for professionals (e.g., preschool teachers, healthcare workers) must include education on the complexities of genital anatomy, normal variations, and the potential for misidentification. This will help ensure reports are based on informed observation, not unfounded suspicion.

- Strengthen Proportionality in Investigations: Police and prosecutors should conduct more thorough preliminary investigations before resorting to coercive measures like forced genital examinations. The possibility of obtaining information from guardians should be explored first to avoid unnecessary trauma to children, in line with the principles of SDG 3 and SDG 16.

- Minimize Invasiveness of Examinations: When an examination is deemed necessary, it must be conducted with utmost discretion and support for the child. Models such as using a medical expert for in-situ assessments during routine activities (e.g., diaper changes) should be explored.

- Establish Multidisciplinary Expert Panels: To address the ambiguity in medical assessments, all FGM-related examinations should be reviewed by a multidisciplinary panel of medical specialists to reach a consensus, ensuring evidence is robust and reducing the need for repeated examinations.

- Educate the Judiciary: Courts require better education on the complexities of FGM diagnosis and the limitations of medical evidence. This is essential for upholding the rule of law and ensuring fair trials, a cornerstone of SDG 16.

- Foster Trust and Collaboration: Shift policy focus from control and suspicion to building trust and partnership with immigrant communities. Acknowledging the reality of cultural change is the first step toward creating effective, non-stigmatizing prevention strategies that support SDG 5 and SDG 10.

6. Conclusion

While Sweden’s commitment to eliminating FGM is commendable and aligns with SDG 5, its current implementation methods create a state of structural injustice that conflicts with SDG 10 and SDG 16. The reliance on disproportionate, invasive measures that disproportionately target immigrant communities has yielded no prosecutions while causing significant harm and eroding trust. A fundamental policy reassessment is required to move towards a more collaborative, evidence-based, and proportionate approach. Such a shift is essential to protect the rights and well-being of all children and build the just, inclusive institutions envisioned by the Sustainable Development Goals.

Analysis of Sustainable Development Goals in the Article

1. Which SDGs are addressed or connected to the issues highlighted in the article?

The article addresses several Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by examining the complex social, legal, and health issues surrounding Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) policies in Sweden. The primary SDGs identified are:

- SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being: The article discusses the physical and psychological health consequences for girls, not only from FGM itself but also from the invasive and often traumatic investigative procedures, such as forced genital examinations. It mentions physical symptoms like “urinary problems” and “traces of blood in her urine,” as well as the “emotional and psychological impacts” of the interventions.

- SDG 5: Gender Equality: This is a central theme, as FGM is explicitly defined in the article as “a form of violence against women and girls” and a harmful practice. The entire discussion revolves around policies designed to eliminate this specific form of gender-based violence.

- SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities: The article’s core argument is that FGM policies disproportionately affect and marginalize specific immigrant communities. It highlights issues of “structural injustice,” “over-policing,” “ethnic discrimination,” and the creation of “suspect communities,” which are all dimensions of inequality.

- SDG 16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions: The analysis critically examines the effectiveness, proportionality, and fairness of legal and institutional frameworks. It delves into police investigations, the role of prosecutors, child protection services, and court proceedings, questioning whether these institutions deliver justice or inadvertently cause harm and violate individual rights.

2. What specific targets under those SDGs can be identified based on the article’s content?

Based on the issues discussed, the following specific SDG targets are relevant:

-

SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being

- Target 3.8: Achieve universal health coverage, including financial risk protection, access to quality essential health-care services and access to safe, effective, quality and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all. The article implicitly addresses this target by discussing the quality of healthcare provided during genital examinations, noting that they are not always conducted by specialists with “appropriate expertise” and often lack adequate psychological support for the child, thus questioning the quality and appropriateness of the care delivered to this specific group.

-

SDG 5: Gender Equality

- Target 5.2: Eliminate all forms of violence against all women and girls in the public and private spheres, including trafficking and sexual and other types of exploitation. The article directly frames FGM as “a form of violence against women and girls” and analyzes the legal and policy measures intended to combat it.

- Target 5.3: Eliminate all harmful practices, such as child, early and forced marriage and female genital mutilation. This target is the central focus of the article. The entire text is a critical examination of Sweden’s strategies to eliminate FGM within its borders.

-

SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities

- Target 10.2: By 2030, empower and promote the social, economic and political inclusion of all, irrespective of age, sex, disability, race, colour, ethnicity, origin, religion or economic or other status. The article argues that current FGM policies lead to the marginalization and social exclusion of immigrant communities, creating “suspect communities” and reinforcing stereotypes, which works against their social inclusion.

- Target 10.3: Ensure equal opportunity and reduce inequalities of outcome, including by eliminating discriminatory laws, policies and practices and promoting appropriate legislation, policies and action in this regard. The paper’s central thesis is that “well-meaning policies may inadvertently contribute to the social and legal marginalisation of immigrant communities” and result in “ethnic discrimination.” It calls for a re-evaluation of these practices to ensure they do not produce unequal outcomes.

-

SDG 16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions

- Target 16.2: End abuse, exploitation, trafficking and all forms of violence against and torture of children. While the policies aim to prevent FGM (a form of violence against children), the article argues that the interventions themselves, such as “forced genital examinations” and “harsh police questioning,” can be psychologically harmful and abusive to children.

- Target 16.3: Promote the rule of law at the national and international levels and ensure equal access to justice for all. The article questions the proportionality and fairness of the justice system’s application, highlighting how “lawful decisions” can result in “structural injustice.” The discussion of court cases and the reliance on ambiguous medical evidence touch upon the challenges of ensuring equal and fair justice.

- Target 16.7: Ensure responsive, inclusive, participatory and representative decision-making at all levels. The article advocates for more nuanced, trust-building approaches that are sensitive to the “evolving cultural contexts” of affected communities, suggesting that current top-down, control-based policies are not responsive or inclusive.

3. Are there any indicators mentioned or implied in the article that can be used to measure progress towards the identified targets?

The article provides several quantitative and qualitative indicators that can be used to measure the situation and the impact of the policies discussed:

-

Indicators for SDG 5 (Target 5.3)

- Prevalence of FGM: The article discusses the discrepancy between the assumed high prevalence of FGM and the actual evidence. It notes that “Europe has seen a notable scarcity of identified illegal cases” and that in the “vast majority of instances, either illegal FGM did not occur or could not be proven.” This directly relates to Indicator 5.3.2 (Proportion of girls and women aged 15-49 years who have undergone female genital mutilation/cutting).

-

Indicators for SDG 10 (Target 10.3)

- Reports of Discrimination: The article mentions that families investigated for FGM “may interpret these inquiries as acts of ethnic discrimination” and cites reports made to the “Equality Ombudsman.” One case resulted in a municipality being “found guilty of ethnic discrimination.” This serves as a direct measure related to Indicator 10.3.1 (Proportion of population reporting having personally felt discriminated against or harassed).

-

Indicators for SDG 16 (Targets 16.2 & 16.3)

- Justice System Statistics: The article provides specific numbers on the justice system’s activities: an archive of “230 case files,” “101 included genital examinations,” and only “three cases of confirmed FGM have reached criminal court.” The fact that forced examinations have “not resulted in any prosecutions” is a key indicator of the system’s effectiveness and proportionality.

- Child Protection Interventions: The article quantifies the use of coercive measures, identifying “58 cases involving genital examinations conducted in Sweden without the knowledge or consent of the girls’ parents.” The number of children taken into “state custody” is another concrete indicator of institutional actions.

- Experience of Violence during Investigations: The article describes girls suffering “an emotional breakdown” from “harsh police questioning” and being “severely affected” by separation from their mothers. These qualitative accounts serve as indicators of psychological violence experienced by children during state interventions, relevant to Indicator 16.2.1 (Proportion of children aged 1-17 years who experienced any physical punishment and/or psychological aggression by caregivers).

4. Table of SDGs, Targets, and Indicators

| SDGs | Targets | Indicators Identified in the Article |

|---|---|---|

| SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being | 3.8: Achieve universal health coverage and access to quality essential health-care services. |

|

| SDG 5: Gender Equality |

5.2: Eliminate all forms of violence against women and girls.

5.3: Eliminate all harmful practices, such as FGM. |

|

| SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities |

10.2: Promote social inclusion of all, irrespective of ethnicity or origin.

10.3: Ensure equal opportunity and eliminate discriminatory practices. |

|

| SDG 16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions |

16.2: End abuse and all forms of violence against children.

16.3: Promote the rule of law and ensure equal access to justice. 16.7: Ensure responsive and inclusive decision-making. |

|

Source: nature.com

What is Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0