Polio: Reviewing its History and the Development of its Vaccine – Contagion Live

Report on the History and Eradication of Poliomyelitis in the Context of Sustainable Development Goals

Introduction: The Global Fight Against Polio

The effort to eradicate poliomyelitis (polio) represents one of modern history’s most significant public health undertakings. This initiative is intrinsically linked to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being), which aims to end the epidemics of communicable diseases by 2030. The history of polio, from its emergence as a major public health threat to the development of vaccines and the near-total eradication, offers critical lessons on the importance of scientific innovation, robust health systems, and global cooperation in achieving sustainable development.

Historical Context and Public Health Paradoxes

While polio is an ancient disease, its prevalence surged during the industrial age of the late 19th century. Urbanization led to higher population densities, facilitating greater transmission. Paradoxically, concurrent improvements in sanitation, a key target of SDG 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation), inadvertently contributed to an increase in polio cases. According to Andrea Prinzi, PhD, MPH, SM(ASCP), prior to widespread sanitation, infants in less hygienic environments were often exposed to the poliovirus while still protected by maternal antibodies, leading to natural immunity. The introduction of cleaner living conditions reduced this early, passive immunization, leaving children vulnerable to infection later in life when the disease is more likely to cause paralysis. This highlights the complex interplay between development indicators and the need for comprehensive public health strategies, such as vaccination, to complement infrastructure improvements.

Vaccine Development: A Milestone for Global Health (SDG 3 & SDG 9)

The development of polio vaccines in the mid-20th century was a landmark achievement for SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure) and a turning point for SDG 3. Two primary vaccines emerged from the work of competing scientists.

Dr. Jonas Salk’s Inactivated Polio Vaccine (IPV)

Dr. Jonas Salk pursued an unconventional approach by developing a vaccine using a “killed” or inactivated virus. This diverged from the prevailing scientific focus on live-attenuated viruses. Working with a small team and some government funding, Salk’s innovation provided the first widely used tool against polio.

Dr. Albert Sabin’s Oral Polio Vaccine (OPV)

Dr. Albert Sabin developed a live-attenuated oral vaccine. The OPV had significant advantages for global health campaigns, particularly in regions with limited healthcare infrastructure. Its benefits included:

- Low cost of production.

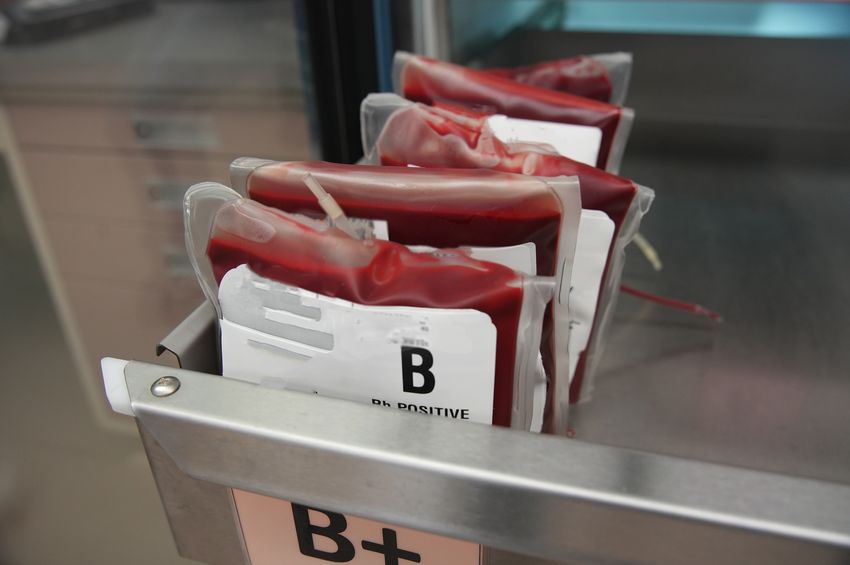

- Ease of administration (oral drops), eliminating the need for sterile needles and trained injectors.

This accessibility was crucial for advancing the goal of universal health coverage, a cornerstone of SDG 3.

Challenges in Vaccine Deployment and Public Trust

The path to polio eradication was marked by significant challenges, including ethical lapses and manufacturing failures that threatened public trust and progress towards health goals.

Ethical Considerations and Institutional Strengthening (SDG 10 & SDG 16)

The testing phases for both the Salk and Sabin vaccines involved ethically questionable practices. Research subjects included marginalized and vulnerable populations such as:

- Incarcerated individuals

- Children with disabilities

These events, which contravene the principles of SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities), were instrumental in the subsequent development of robust ethical review boards and regulatory frameworks. This institutional strengthening is a core component of SDG 16 (Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions), ensuring that scientific advancement does not come at the expense of human rights.

Manufacturing Failures and Vaccine Hesitancy

A major setback occurred when a manufacturing error by one producer led to the release of Salk vaccine batches containing live poliovirus. This disastrous event caused numerous infections and eroded public trust in the IPV, despite its proven safety and efficacy when produced correctly. This incident underscores the critical importance of quality control and resilient infrastructure as outlined in SDG 9. The resulting public fear prompted a transition in the United States to Sabin’s oral vaccine, which was already in wide use globally. Over time, due to rare cases of vaccine-derived polio associated with the OPV, the US and many other countries have since switched back to the IPV.

Progress Towards Global Eradication: A Public Health Triumph

Despite the challenges, the coordinated global vaccination effort has been remarkably successful, demonstrating the power of collective action in achieving SDG 3.

Impact on Global Health and Well-being

The impact of vaccination was swift and dramatic. In the United States, the success of the program can be seen in the following timeline:

- Pre-1955: The average number of polio cases exceeded 45,000 annually.

- By 1962: Following several years of widespread vaccination, the number of cases dropped to 910.

This success has been replicated globally, preventing millions of cases of paralysis and death.

The Final Frontier: Endemic Polio and Global Partnerships (SDG 17)

Today, wild poliovirus remains endemic in only two countries: Pakistan and Afghanistan. The final push for eradication exemplifies SDG 17 (Partnerships for the Goals), requiring sustained collaboration between governments, the World Health Organization, and other international partners. The persistence of polio in these regions, often marked by conflict and instability, also highlights the deep connection between public health (SDG 3) and the pursuit of peace and justice (SDG 16).

SDGs Addressed in the Article

The article on the history and eradication efforts of polio touches upon several Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) through its discussion of public health, scientific innovation, institutional ethics, and global cooperation.

-

SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being

This is the most prominent SDG in the article. The entire text is dedicated to polio, a communicable disease, the development of vaccines to combat it, and the global public health initiatives aimed at its eradication. The article highlights the success of vaccination campaigns in drastically reducing the number of polio cases, directly contributing to the goal of ensuring healthy lives and promoting well-being for all.

-

SDG 16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions

The article indirectly addresses this goal by discussing the ethical issues surrounding the development of the polio vaccines. It notes that “Salk and Sabin tested the vaccines on themselves, their families, and marginalized populations such as disabled children and the incarcerated.” The statement that “A lot of ethics review material came from the polio saga” points to the subsequent development of stronger, more accountable, and transparent institutions to govern medical research and protect human subjects.

-

SDG 17: Partnerships for the Goals

This goal is relevant through the mention of collaborative efforts required for vaccine development and distribution. The article states that Jonas Salk “did have some government funding,” indicating a public-private or public-research partnership. Furthermore, the discussion of the “global fight for eradication” and the large-scale “public health immunization efforts” that led to polio being endemic in only two countries implies massive global partnerships involving governments, health organizations, and researchers.

Specific Targets Identified

Based on the article’s content, the following specific targets can be identified:

-

Target 3.3: End epidemics of communicable diseases

The article’s central theme is the effort to end the polio epidemic. It describes the “global fight for eradication” and celebrates the fact that vaccination has led to the “near global eradication of polio,” with the disease remaining endemic in only “Pakistan and Afghanistan.” This directly aligns with the target of ending the epidemics of communicable diseases.

-

Target 3.8: Achieve universal health coverage, including access to affordable essential medicines and vaccines

The development and deployment of two different polio vaccines (Salk’s and Sabin’s) are detailed in the article. It mentions that Sabin’s oral vaccine was “inexpensive and easy to use,” which was crucial for its use “globally, especially in places where these was limited infrastructure.” This focus on creating an affordable and accessible vaccine supports the goal of universal access.

-

Target 3.b: Support the research and development of vaccines and medicines

The article provides a detailed account of the research and development process undertaken by both Jonas Salk and Albert Sabin. It describes their different scientific approaches—Salk’s inactivated virus versus Sabin’s live attenuated virus—which exemplifies the R&D efforts central to this target.

-

Target 16.6: Develop effective, accountable and transparent institutions at all levels

The article implies progress toward this target by highlighting past failures. The unethical testing on marginalized populations and the manufacturing error that led to live virus being distributed created public mistrust. The statement, “A lot of ethics review material came from the polio saga,” suggests that these events spurred the development of more accountable and transparent institutional processes (like ethics review boards) to prevent such occurrences in the future.

Indicators for Measuring Progress

The article mentions or implies several indicators that can be used to measure progress towards the identified targets:

-

Indicator for Target 3.3 (Incidence of disease)

The article provides specific data that serves as an indicator of progress in combating polio. It states that before the vaccine was widely available, “the average number of polio cases in the US was more than 45,000. By 1962… that number had dropped to 910.” This reduction in the number of cases is a direct measure of success. Another indicator is the number of countries where a disease is endemic, which the article notes has been reduced to just two for wild polio.

-

Indicator for Target 3.8 (Vaccine coverage and accessibility)

While not providing a percentage, the article implies vaccine coverage as a key indicator. It mentions that Salk’s vaccine was “used widely in the US” and Sabin’s was “being used globally.” The affordability and ease of use of Sabin’s vaccine (“inexpensive and easy to use…dropped onto a sugar cube”) are described as key factors for its widespread deployment, serving as an implicit indicator of accessibility.

-

Indicator for Target 16.6 (Development of institutional frameworks)

The article implies the establishment of ethical review processes as an indicator of institutional accountability. The phrase “A lot of ethics review material came from the polio saga” suggests that the creation and implementation of such ethical guidelines and review boards are a measurable outcome and an indicator of institutional strengthening in the field of medical research.

Summary of Findings

| SDGs | Targets | Indicators |

|---|---|---|

| SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being |

Target 3.3: End epidemics of communicable diseases.

Target 3.8: Achieve universal health coverage, including access to affordable essential medicines and vaccines. Target 3.b: Support the research and development of vaccines and medicines. |

– Reduction in the number of polio cases (from over 45,000 to 910 in the US). – Reduction in the number of countries where polio is endemic (down to 2). – Widespread deployment of vaccines (“used widely in the US,” “being used globally”). – Development of an “inexpensive and easy to use” vaccine to ensure accessibility. |

| SDG 16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions | Target 16.6: Develop effective, accountable and transparent institutions at all levels. | – The development of “ethics review material” following unethical testing practices during the “polio saga.” |

| SDG 17: Partnerships for the Goals | Target 17.17: Encourage and promote effective public, public-private and civil society partnerships. |

– Mention of “government funding” for vaccine research. – Implementation of large-scale “public health immunization efforts” as part of the “global fight for eradication.” |

Source: contagionlive.com

What is Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0