Renewable energy sources for arctic food sufficiency and sustainability – Nature

Report on Renewable Energy, Food Security, and Sustainable Development in the Arctic

This report examines the interconnection between renewable energy, food security, and sustainability within Arctic nations, analyzed through the framework of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The primary focus is on SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy) and its critical role in advancing social, economic, and environmental justice. Achieving SDG 7 is fundamental to making progress on other goals, including SDG 2 (Zero Hunger), by enabling sustainable food production systems. Through a review of available data and case studies, this report outlines pathways for Arctic communities to enhance resilience, achieve food self-sufficiency, and foster economic prosperity by integrating renewable energy while preserving cultural heritage.

1.0 The Imperative of SDG 7 in the Arctic Region

The United Nations’ SDG 7 aims to ensure universal access to affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy by 2030. This goal is not merely about energy infrastructure but is a cornerstone for achieving broader sustainable development. Its key targets include increasing the share of renewable energy, improving energy efficiency, and fostering international cooperation and investment in clean energy technology.

In the Arctic, the successful implementation of SDG 7 is a prerequisite for progress on several other interconnected SDGs:

- SDG 2 (Zero Hunger): Sustainable energy can power local food production, reducing dependence on costly and carbon-intensive food imports and addressing severe food insecurity.

- SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being): Shifting from fossil fuels to clean energy reduces air pollution and associated health risks.

- SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth): Investment in renewable energy infrastructure can create local jobs and stimulate economic diversification.

- SDG 13 (Climate Action): Transitioning to renewables is the most critical action for mitigating climate change, which disproportionately affects the Arctic.

A holistic approach that combines environmental sustainability with economic equity is essential. Strategies must be tailored to the unique cultural and environmental context of the Arctic, recognizing that challenges like biodiversity loss, climate change, and food insecurity are amplified in this region.

2.0 Regional Context: The Arctic

2.1 Geographic and Environmental Profile

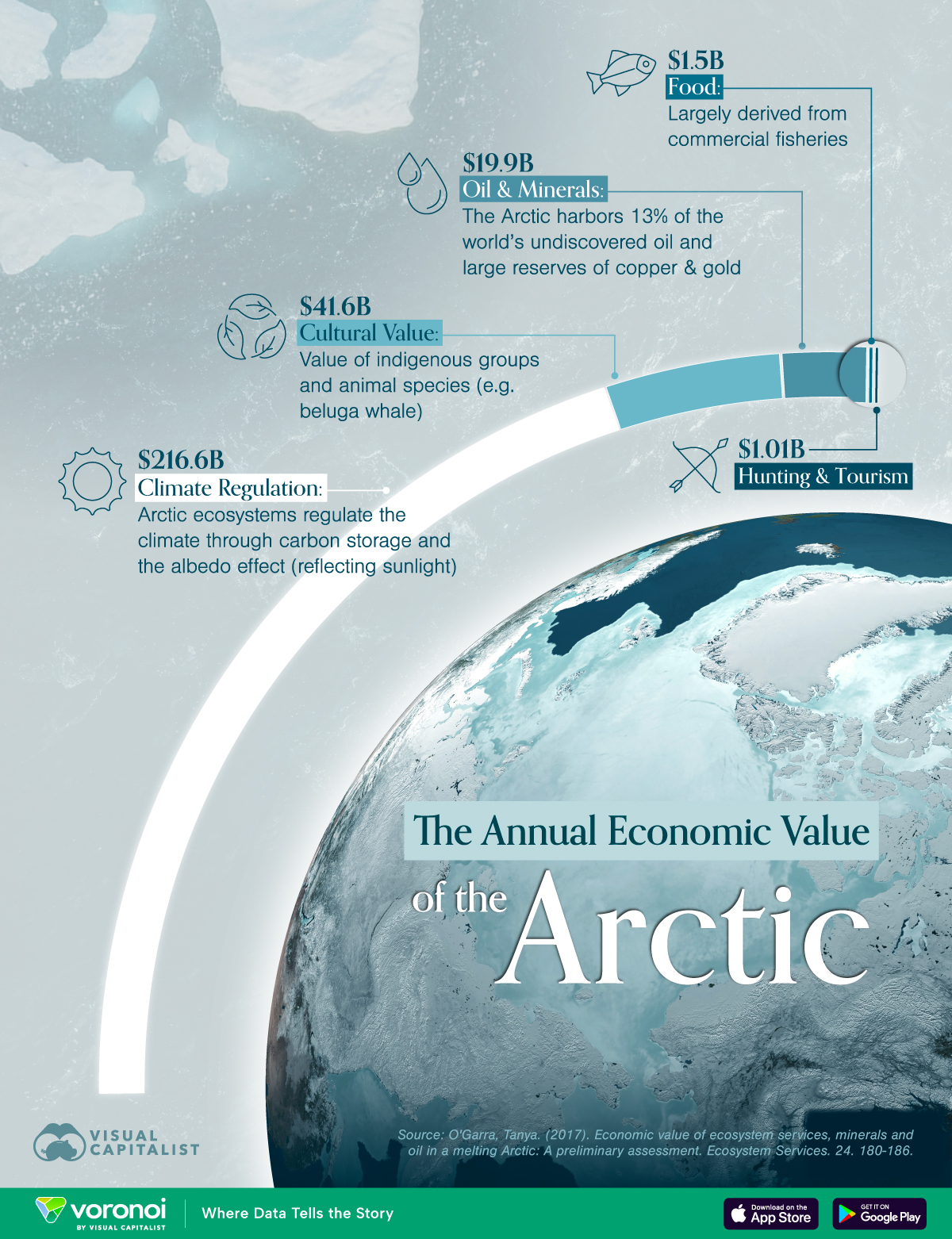

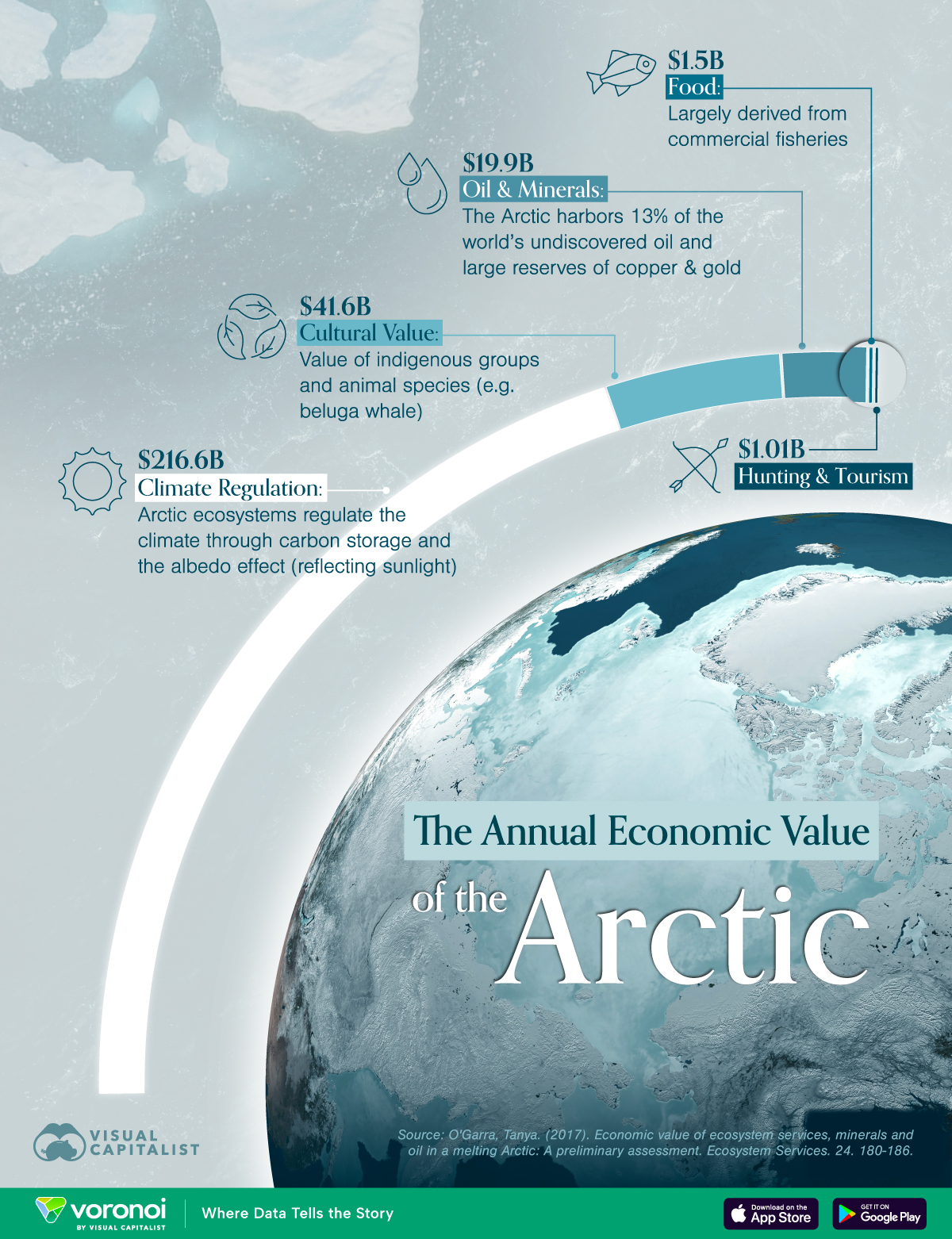

The Arctic region, broadly defined, encompasses parts of nine countries and is characterized by its vast, sparsely populated landscape, harsh climate, and fragile ecosystems. It is rich in natural resources, including minerals, oil, gas, and fisheries, but their extraction poses significant environmental risks, often conflicting with SDG 14 (Life Below Water) and SDG 15 (Life on Land). The region’s varied landscape, from tundra to icecaps, supports unique habitats that are highly vulnerable to climate change. Renewable energy potential, including wind, solar, geothermal, and hydrokinetic, varies significantly across the region.

2.2 Traditional Livelihoods and the Challenge to SDG 2

Traditional food systems in the Arctic, based on hunting, herding, and fishing, are central to Indigenous cultures but are increasingly threatened by climate change. This disruption forces a greater reliance on imported food, which is expensive and contributes to high rates of food insecurity, directly undermining the achievement of SDG 2. Studies show that strengthening local food systems can yield significant economic and environmental benefits. For instance, research in the Canadian Arctic indicates that replacing imported food with locally harvested alternatives could save millions of dollars and substantially reduce carbon emissions, advancing both SDG 2 and SDG 13.

2.3 Demographic Pressures and Social Sustainability

The Arctic’s population of approximately 4 million, with Indigenous peoples comprising about 10%, faces significant demographic shifts. Climate change-induced food scarcity and environmental instability are driving youth migration and disrupting traditional subsistence practices, which are integral to cultural identity (a challenge to SDG 11.4 – protecting cultural heritage). For example, warming waters threaten the Atlantic cod fishery, a vital livelihood for Indigenous fishers in Northern Norway, exacerbating food insecurity and cultural loss. Addressing these challenges requires integrating Indigenous Knowledge with modern adaptation strategies to ensure a just transition that supports both cultural preservation and sustainable development.

3.0 Food Insecurity in the Arctic: A Failure to Achieve SDG 2

Food insecurity is a critical issue across the Arctic, driven by a combination of harsh climate, inadequate infrastructure, high costs of energy and imports, and environmental disruption. The Global Food Security Index reveals significant disparities, even within high-income nations. Achieving SDG 2 requires targeted solutions that address these unique regional challenges.

3.1 Alaska (United States)

One in seven Alaskans experiences food insecurity, with rural communities being the most vulnerable. These communities import 95% of their store-bought food, highlighting a critical gap in local production and a failure to ensure food availability and access under SDG 2.

3.2 Arctic Canada

Food insecurity in Canada’s Arctic territories is disproportionately high compared to the national average, reaching 57% in Nunavut. This is a direct consequence of geographic isolation, high transportation costs, and the impact of climate change on traditional food sources, creating a significant barrier to achieving SDG 2 for Northern and Indigenous populations.

3.3 Finland and Norway

While Finland and Norway rank high on the Global Food Security Index, this masks regional disparities. Both nations’ agricultural systems depend on secure energy supplies, and their Arctic regions face unique vulnerabilities. Norway, despite being a major seafood exporter, has low rankings for food availability and affordability, indicating that national success does not guarantee local food security in line with SDG 2.

3.4 Sweden

Sweden is only 50% food self-sufficient, and its Arctic region imports 91% of its fresh produce. Achieving self-sufficiency and meeting SDG 2 targets in the north would require a massive increase in local production, dependent on sustainable energy solutions.

3.5 Greenland

With only 17% food self-sufficiency and one in ten people facing food insecurity, Greenland exemplifies the profound challenge of achieving SDG 2. Government goals to boost local agriculture are a step forward but require concrete plans for implementation, particularly regarding energy inputs.

4.0 Renewable Energy: The Key to Unlocking Arctic Sustainability (SDG 7)

The Arctic possesses abundant renewable energy resources, including solar, wind, geothermal, and bioenergy. Harnessing this potential is crucial for transitioning away from the current reliance on diesel, which accounts for 80% of energy in Arctic communities. A successful transition to distributed renewable energy systems can advance SDG 7 while supporting other development goals.

While nations like Iceland and Norway are leaders in renewable energy, progress across the Arctic is uneven. Iceland leverages geothermal and hydropower for nearly all its electricity and heating. Greenland has enormous untapped potential in wind and solar, positioning it as a possible future exporter of clean energy products. The Faroe Islands are on track for 100% renewable electricity by 2030. In contrast, many regions in Canada and the US remain heavily dependent on fossil fuels.

However, the pursuit of SDG 7 must not come at the expense of other goals. Renewable energy projects, particularly wind and hydropower, have created land-use conflicts with Indigenous peoples, such as the Sámi in Norway and Sweden. This highlights the risk of “green colonialism,” where the transition to clean energy violates Indigenous rights and undermines cultural livelihoods, creating a direct conflict with SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities). A just transition requires meaningful consultation and benefit-sharing to ensure that renewable energy development is equitable and sustainable for all.

5.0 Case Studies: Pathways and Challenges in Implementing SDGs

5.1 Alaska: Community-Led Energy Transitions

Case studies from Alaska demonstrate that successful renewable energy projects are community-driven and tailored to local needs.

- Technical Challenges: Systems must be designed for extreme cold and integrate with existing infrastructure.

- Human Capital: Local training and project management are essential for long-term success.

- Economic Barriers: Fossil fuel subsidies disincentivize renewable adoption.

- Social and Political Hurdles: Community trust and involvement are paramount.

Successful projects in communities like Kodiak (hydropower and wind) and Kongiganak (wind) have reduced diesel dependence, lowered energy costs, and created local economic benefits, advancing SDG 7, SDG 8, and SDG 11 (Sustainable Communities).

5.2 Comparative Cases: Iqaluit, Tiksi, and the Faroe Islands

A comparison of these three locations reveals diverse approaches to the energy transition, underscoring the importance of SDG 17 (Partnerships for the Goals) for knowledge sharing.

- Iqaluit, Canada: Remains heavily diesel-dependent, illustrating the challenge of overcoming aging infrastructure and logistical hurdles to meet SDG 7.

- Faroe Islands: Demonstrates an ambitious, investment-driven path to 100% renewables, serving as a model for what is possible with strong political will.

- Tiksi, Russia: A hybrid wind-diesel model shows a pragmatic, transitional approach that has significantly reduced fossil fuel consumption.

5.3 The Sámi Experience: A Conflict Between SDGs

The experience of the Sámi people in Norway highlights a critical challenge: the potential for renewable energy projects to infringe upon Indigenous rights. Wind farms and dams have disrupted reindeer herding, a cornerstone of Sámi culture and economy. This case illustrates that achieving SDG 7 cannot be pursued in isolation. Without respecting the rights and livelihoods of Indigenous peoples, such projects risk undermining SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities) and failing the core principle of a just transition.

6.0 Key Takeaways for an SDG-Focused Arctic Future

- Renewable energy projects must be developed in full partnership with Indigenous communities, respecting their land rights, cultural values, and livelihoods to ensure a just transition that aligns with SDG 10.

- Overcoming the technical, economic, and political barriers to renewable energy in the Arctic requires tailored solutions, strong governance, and streamlined funding and permitting processes to accelerate progress on SDG 7.

- Properly implemented, renewable energy initiatives can generate local wealth, create jobs (SDG 8), and enhance community resilience (SDG 11) by reducing dependence on volatile fossil fuel markets.

- Financial and technical risks can be mitigated through grants, strategic partnerships, and by building local capacity, ensuring the long-term sustainability of projects.

- Regional and international collaboration under SDG 17 is essential to share best practices, drive innovation in Arctic-appropriate technologies, and accelerate the achievement of the SDGs across the entire region.

7.0 Conclusion

The Arctic stands at a critical juncture where the pursuit of sustainable development is both urgent and complex. The region’s climatic conditions and isolation necessitate decentralized energy solutions. Integrating renewable energy sources is the most viable path forward to address the interconnected challenges of energy access, food security, and climate change. Achieving SDG 7 is the lynchpin for making meaningful progress on SDG 2, SDG 13, and the broader 2030 Agenda.

While leaders like Iceland and Norway demonstrate what is possible, all Arctic regions can accelerate their energy transitions. Success, however, depends on a holistic approach. Projects must be implemented with the full consultation and partnership of local and Indigenous communities, ensuring that the transition is just, equitable, and respects cultural heritage. By doing so, the Arctic can transform its challenges into opportunities, becoming a global model for remote sustainability and resilient development.

Analysis of Sustainable Development Goals in the Article

1. Which SDGs are addressed or connected to the issues highlighted in the article?

The article primarily focuses on the intersection of energy, food security, and sustainability in the Arctic, directly and indirectly addressing several Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The following SDGs are identified:

- SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy): This is the central theme of the article, explicitly mentioned and analyzed in depth, focusing on ensuring access to affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy for all Arctic communities.

- SDG 2 (Zero Hunger): The article extensively discusses food insecurity, food self-sufficiency, and the promotion of sustainable local food production systems as a critical issue in the Arctic, directly linking it to the availability of sustainable energy.

- SDG 13 (Climate Action): The article connects the transition to renewable energy with mitigating climate change and highlights how climate change impacts traditional food sources and livelihoods in the Arctic.

- SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth): The text links the adoption of renewable energy and local food systems to promoting economic justice, creating local employment opportunities, and fostering economically prosperous and resilient communities.

- SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being): The article mentions that access to modern energy is vital for the health and well-being of society and notes the adverse health effects of relying on polluting fuels like diesel.

- SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities): The article highlights the disproportionate impact of food insecurity and energy challenges on Indigenous peoples. It also discusses the violation of Indigenous rights in the context of renewable energy projects, pointing to the need for equitable development.

- SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities): The focus on making remote Arctic communities resilient, sustainable, and addressing their unique infrastructure challenges aligns with the goals of SDG 11.

- SDG 16 (Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions): The article underscores the importance of community involvement, stakeholder collaboration, and inclusive, participatory decision-making, especially concerning the rights of Indigenous peoples like the Sámi, which is a key aspect of this goal.

- SDG 17 (Partnerships for the Goals): The need for international collaboration, knowledge sharing, and partnerships between governments, private entities, and communities to tackle energy challenges is a recurring theme.

2. What specific targets under those SDGs can be identified based on the article’s content?

Based on the article’s discussion of policies, projects, and challenges, several specific SDG targets can be identified:

-

SDG 7: Affordable and Clean Energy

- Target 7.1: By 2030, ensure universal access to affordable, reliable and modern energy services. The article’s core mission is to examine how Arctic regions can achieve this, moving away from expensive and unreliable diesel systems.

- Target 7.2: By 2030, increase substantially the share of renewable energy in the global energy mix. This is demonstrated through numerous case studies in Alaska, Canada, Russia, and the Nordic countries, which detail projects involving wind, solar, hydro, and biomass energy to replace fossil fuels.

- Target 7.3: By 2030, double the global rate of improvement in energy efficiency. This is implied in projects that reduce diesel consumption, such as the installation of electric thermal stoves in Kongiganak and the development of hybrid wind-diesel systems in Tiksi.

- Target 7.a: By 2030, enhance international cooperation to facilitate access to clean energy research and technology… and promote investment in energy infrastructure and clean energy technology. The article explicitly calls for “international collaboration and knowledge transferability” and highlights the role of federal funding and international investment in various projects.

-

SDG 2: Zero Hunger

- Target 2.1: By 2030, end hunger and ensure access by all people, in particular the poor and people in vulnerable situations, including infants, to safe, nutritious and sufficient food all year round. The article addresses this by detailing the high rates of food insecurity in Arctic communities, especially among Indigenous peoples, and exploring solutions to improve access to food.

- Target 2.4: By 2030, ensure sustainable food production systems and implement resilient agricultural practices… that strengthen capacity for adaptation to climate change. This is supported by the discussion of using renewable energy to power community gardens and greenhouses, which enhances local food production, reduces dependence on imports, and builds resilience.

-

SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities

- Target 10.2: By 2030, empower and promote the social, economic and political inclusion of all, irrespective of age, sex, disability, race, ethnicity, origin, religion or economic or other status. The article’s focus on the unique vulnerabilities of Indigenous communities and the need to respect their rights and cultural practices in energy development directly relates to this target.

-

SDG 16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions

- Target 16.7: Ensure responsive, inclusive, participatory and representative decision-making at all levels. The article stresses that “meaningful consultation and active Indigenous involvement in planning and decision-making are essential” and contrasts successful projects with strong community support (e.g., Kongiganak) with conflicts arising from a lack of consultation (e.g., the Sámi experience).

3. Are there any indicators mentioned or implied in the article that can be used to measure progress towards the identified targets?

The article provides numerous quantitative and qualitative data points that can serve as indicators to measure progress towards the identified SDG targets.

-

Indicators for SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy)

- Proportion of population with access to electricity (Indicator 7.1.1): Implied by the statement that “80% of Arctic communities rely on diesel for their energy needs,” indicating a lack of access to modern, sustainable energy infrastructure.

- Renewable energy share in the total final energy consumption (Indicator 7.2.1): The article provides specific figures for several regions: Iceland (87% renewable energy supply, 100% renewable electricity), Norway (>90% renewable energy production), and Kodiak, AK (99% renewable energy). It also notes goals, such as the Faroe Islands aiming for 100% by 2030.

- Energy intensity measured in terms of primary energy and GDP (Indicator 7.3.1): Progress is implied through specific reductions in fossil fuel use, such as Kongiganak saving 24,000 gallons of diesel annually and Tiksi reducing diesel consumption by 500 tons annually.

-

Indicators for SDG 2 (Zero Hunger)

- Prevalence of undernourishment (Indicator 2.1.1) / Prevalence of moderate or severe food insecurity (Indicator 2.1.2): The article provides specific rates of food insecurity: “One in seven Alaskans,” “1 in 10 Greenlanders,” and regional rates in Canada (e.g., 57% in Nunavut). The Global Food Security Index rankings for various countries also serve as a high-level indicator.

- Proportion of agricultural area under productive and sustainable agriculture (Indicator 2.4.1): Progress is measured by food self-sufficiency rates, such as Sweden (50%), Iceland (53%), and Greenland (17%), and the high dependence on imports in other areas (95% in rural Alaska, 91% in Arctic Sweden).

-

Indicators for SDG 13 (Climate Action)

- Greenhouse gas emissions reductions: The article mentions a study where local food production in Canada could “reduce carbon emissions by approximately half.” Reductions in diesel consumption also directly translate to lower GHG emissions.

-

Indicators for SDG 16 (Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions)

- Proportion of population satisfied with their last experience of public services (Indicator 16.6.2): Measured qualitatively through the case studies. The article describes projects where community involvement led to success and local pride (e.g., Galena, Kotzebue) versus projects where a lack of consultation led to conflict and opposition (the Sámi experience).

4. Table of SDGs, Targets, and Indicators

| SDGs | Targets | Indicators Identified in the Article |

|---|---|---|

| SDG 7: Affordable and Clean Energy |

7.1: Ensure universal access to affordable, reliable and modern energy services.

7.2: Increase substantially the share of renewable energy. 7.a: Enhance international cooperation and promote investment in clean energy. |

– 80% of Arctic communities rely on diesel. – Case studies of communities transitioning from diesel to renewables (e.g., Kongiganak, Kodiak). – Renewable energy share: Iceland (87%), Norway (>90%), Kodiak (99%). – Installed capacity: Kotzebue (2250 kW wind, 576 kW solar), Tiksi (900 kW wind). – Renewable energy goals: Faroe Islands (100% by 2030). – Mention of federal funding (e.g., Canada’s “Indigenous Off-Diesel Initiative”) and international investment. |

| SDG 2: Zero Hunger |

2.1: End hunger and ensure access to safe, nutritious and sufficient food.

2.4: Ensure sustainable food production systems and resilient agricultural practices. |

– Food insecurity rates: 57% in Nunavut; 1 in 7 Alaskans; 1 in 10 Greenlanders. – Global Food Security Index rankings for Arctic countries. – Food self-sufficiency rates: Sweden (50%), Iceland (53%), Greenland (17%). – Dependence on imported food: 95% in rural Alaska; 91% in Arctic Sweden. – Promotion of community gardens and greenhouses powered by renewable energy. |

| SDG 13: Climate Action | 13.2: Integrate climate change measures into national policies, strategies and planning. |

– Reduction in diesel consumption (e.g., Tiksi: 500 tons/year). – Potential to reduce carbon emissions by half through local food production in Canada. – Transition to zero-emission greenhouses and renewable energy systems as a climate mitigation strategy. |

| SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities | 10.2: Empower and promote the social, economic and political inclusion of all, especially Indigenous peoples. |

– Data showing Indigenous peoples are “particularly at risk of being food insecure.” – Discussion of Sámi land rights being treated as “sacrifice zones” for green energy projects. – Call for respecting cultural practices and livelihoods in project development. |

| SDG 16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions | 16.7: Ensure responsive, inclusive, participatory and representative decision-making. |

– Qualitative evidence from case studies: successful projects had “robust community involvement” (Galena) and “community support” (Kongiganak). – Negative example of the Sámi, who feel their input is “often ignored.” – Emphasis on the need for “meaningful consultation and active Indigenous involvement.” |

Source: nature.com

What is Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0