Structural limitations of the decarbonization state – Nature

Report on State-Led Decarbonization Efforts and the Sustainable Development Goals

Introduction: The Implementation Gap in Achieving SDG 13 (Climate Action)

In pursuit of net-zero climate targets, as mandated by Sustainable Development Goal 13 (Climate Action), numerous states have amplified their commitments to decarbonize their economies. However, a significant implementation gap persists between these ambitious goals and the enactment of effective policies. This disparity is exacerbated by political pressures that encourage climate policy backsliding. This report posits that this gap can be better understood by examining the inherent functions of the prevailing liberal capitalist state model.

Core State Functions and Their Conflict with Decarbonization

The Challenge to Foundational State Mandates

The emerging “decarbonization state” is characterized by a strategic shift from fossil fuel dependency towards renewable energy sources, a core tenet of SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy). This fundamental transformation, however, directly challenges the traditional functions of the state, which are essential for maintaining stability and achieving broader development goals.

- Ensuring Economic Growth (SDG 8): The state’s primary function of fostering economic growth, aligned with SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth), is traditionally rooted in fossil-fuel-intensive industries. The transition to a decarbonized economy disrupts this model, creating tension between environmental objectives and established economic paradigms.

- Maintaining Legitimacy (SDG 16): The state must maintain public trust and political legitimacy to function effectively, a principle central to SDG 16 (Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions). The profound societal and economic changes required for decarbonization can provoke public opposition and political instability, thereby threatening this legitimacy.

- Providing Security (SDG 16): National security, intrinsically linked to energy security, has long been dependent on stable access to fossil fuels. The transition to renewable energy systems introduces new geopolitical and infrastructural vulnerabilities, challenging the state’s capacity to provide security as outlined in SDG 16.

The Decarbonization State and the SDG Framework

Conceptualizing the Transition to Renewable Energy

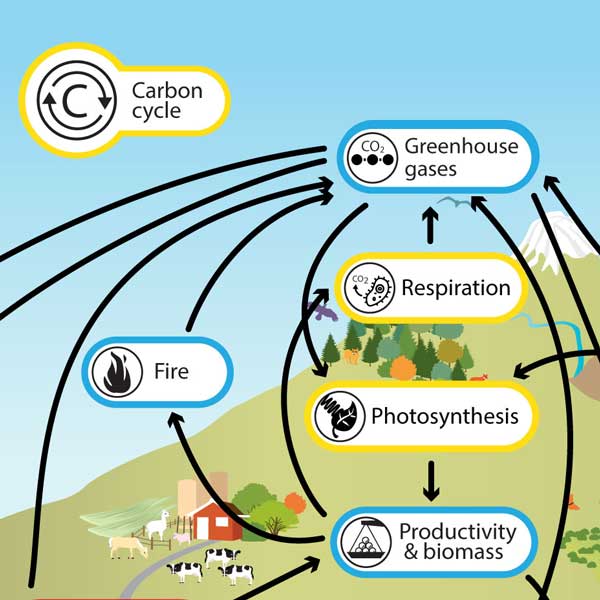

The shift towards decarbonization represents more than a mere improvement of existing technologies. It constitutes a complete transformation of the state’s role in energy governance. This process aims to fundamentally realign national economies with the objectives of SDG 7 and SDG 13 by replacing the fossil fuel paradigm with one based on renewable energy.

Implications for Sustainable Governance

The analysis reveals a structural conflict between the state’s climate commitments and its foundational functions. This tension is a primary driver of the implementation gap, hindering progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals. Understanding this dynamic is critical for designing policies that can successfully navigate the transition.

- The pressure to maintain economic growth (SDG 8) often leads to the subsidization of legacy industries, slowing the phase-out of fossil fuels.

- Fear of losing political legitimacy (SDG 16) can deter governments from implementing ambitious but potentially unpopular climate policies.

- Concerns over energy security (SDG 16) during the transition can lead to continued investment in fossil fuel infrastructure, undermining the goals of SDG 7 and SDG 13.

Conclusion and Future Research Directions

The successful implementation of decarbonization policies in line with the SDGs requires a re-evaluation of the state’s core functions. The inherent contradictions within the liberal capitalist state model pose significant structural barriers to achieving a sustainable and just transition. Future research should focus on developing new frameworks for governance that can reconcile these competing demands.

Recommended Avenues for Investigation:

- Developing alternative models of economic prosperity that decouple growth from carbon emissions, thereby aligning SDG 8 with SDG 13.

- Exploring new mechanisms for building public consensus and democratic legitimacy for transformative climate action, strengthening the foundations of SDG 16.

- Analyzing the geopolitical and security implications of a global energy system based on renewables to create resilient frameworks for SDG 7 and SDG 16.

1. Which SDGs are addressed or connected to the issues highlighted in the article?

The article’s abstract on the challenges of decarbonization connects to several Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The primary focus is on climate and energy, but the analysis of state functions and policy implementation broadens the scope to include goals related to economic models and governance.

-

SDG 13: Climate Action

This is the most central SDG to the article. The text explicitly revolves around the effort “to achieve net-zero climate targets” and the ambition of states to “decarbonize their economies.” The core problem identified is the “implementation gap” in climate policy, which directly pertains to taking urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts.

-

SDG 7: Affordable and Clean Energy

The article directly addresses this goal by defining the “nascent decarbonization state as increasingly aiming to shift from fossil fuels towards renewable energy.” This highlights the transition to clean energy sources as a fundamental strategy for decarbonization, which is the core of SDG 7.

-

SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth

This goal is relevant because the article identifies a primary conflict between decarbonization efforts and a basic function of the “liberal capitalist state,” which is “ensuring economic growth.” The text argues that the transformation required for decarbonization “challenges” this function, implying a need to rethink the relationship between economic models and environmental sustainability.

-

SDG 16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions

The article’s focus on the “implementation gap between ambitious targets and actual policies” points directly to the effectiveness of state institutions. Furthermore, it mentions that the transition challenges the state’s ability to maintain “legitimacy,” which is a cornerstone of stable and effective governance as promoted by SDG 16.

-

SDG 17: Partnerships for the Goals

The article discusses the “implementation gap” and the conflict between decarbonization and other state functions. This points to a lack of policy coherence, which is a key aspect of SDG 17. Achieving complex goals like decarbonization requires integrated and coherent policies that align economic, social, and environmental objectives.

2. What specific targets under those SDGs can be identified based on the article’s content?

Based on the issues discussed, several specific SDG targets can be identified:

-

Target 13.2: Integrate climate change measures into national policies, strategies and planning.

The article’s entire premise is built around this target. It discusses how states have “ramped up ambitions to decarbonize their economies” and set “ambitious targets.” However, it highlights a “serious implementation gap between ambitious targets and actual policies,” which is a direct commentary on the challenges of integrating climate measures effectively into national policy.

-

Target 7.2: By 2030, increase substantially the share of renewable energy in the global energy mix.

This target is directly referenced when the article describes the goal of the decarbonization state as aiming to “shift from fossil fuels towards renewable energy.” This transition is presented as the primary mechanism for achieving climate goals.

-

Target 8.4: Improve progressively, through 2030, global resource efficiency in consumption and production and endeavour to decouple economic growth from environmental degradation.

The article implies this target by framing the central problem as a conflict between decarbonization and the state’s function of “ensuring economic growth.” The challenge described is precisely the difficulty of decoupling economic activity from the environmental degradation caused by fossil fuels. The article suggests that the current “liberal capitalist state” model is struggling to achieve this decoupling.

-

Target 16.6: Develop effective, accountable and transparent institutions at all levels.

The “serious implementation gap” mentioned in the article is a symptom of institutions that are not fully effective in translating policy ambitions into reality. The discussion of the state’s struggle to maintain “legitimacy” while pursuing decarbonization also relates to the need for accountable and trusted institutions that can manage such a complex transformation.

-

Target 17.14: Enhance policy coherence for sustainable development.

The article’s core argument is that decarbonization policies are in conflict with other “basic functions” of the state, such as “ensuring economic growth” and “providing security.” This describes a lack of policy coherence, where climate goals are undermined by competing objectives within the state’s framework.

3. Are there any indicators mentioned or implied in the article that can be used to measure progress towards the identified targets?

The abstract is conceptual and does not provide quantitative data, but it implies several qualitative and quantitative indicators for measuring progress:

-

Indicator for Target 13.2:

The “implementation gap between ambitious targets and actual policies” is itself a key qualitative indicator. Progress would be measured by the reduction of this gap, meaning the degree to which enacted policies align with stated “net-zero climate targets.”

-

Indicator for Target 7.2:

The primary indicator is the rate of the “shift from fossil fuels towards renewable energy.” This can be measured quantitatively as the percentage share of renewable energy in a country’s total energy consumption, and the corresponding decline in the share of fossil fuels.

-

Indicator for Target 8.4:

An implied indicator is the extent to which economic growth is decoupled from carbon emissions. The article suggests this is a major challenge, so measuring CO2 emissions per unit of GDP would be a relevant indicator to track progress toward resolving the conflict between “ensuring economic growth” and decarbonization.

-

Indicator for Target 16.6:

The effectiveness of institutions can be qualitatively assessed by the size of the “implementation gap.” Furthermore, public trust and the state’s “legitimacy” in the eyes of its citizens, especially concerning climate policies, can be measured through surveys and serve as an indicator of institutional accountability.

-

Indicator for Target 17.14:

The degree of policy coherence can be assessed by analyzing the extent to which national economic, security, and energy policies support or contradict the state’s “net-zero climate targets.” The existence of subsidies for fossil fuels while promoting renewables would be a clear indicator of a lack of coherence.

4. Table of SDGs, Targets, and Indicators

| SDGs | Targets | Indicators (as implied in the article) |

|---|---|---|

| SDG 13: Climate Action | 13.2: Integrate climate change measures into national policies, strategies and planning. | The size of the “implementation gap” between “ambitious targets” and “actual policies.” |

| SDG 7: Affordable and Clean Energy | 7.2: Increase substantially the share of renewable energy in the global energy mix. | The rate of the “shift from fossil fuels towards renewable energy.” |

| SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth | 8.4: Improve global resource efficiency and decouple economic growth from environmental degradation. | The degree of conflict or synergy between “ensuring economic growth” and decarbonization efforts. |

| SDG 16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions | 16.6: Develop effective, accountable and transparent institutions at all levels. | The “implementation gap” as a measure of institutional ineffectiveness; the level of state “legitimacy” in managing the transition. |

| SDG 17: Partnerships for the Goals | 17.14: Enhance policy coherence for sustainable development. | The extent to which climate policies conflict with other state functions like economic growth and security. |

Source: nature.com

What is Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0