Trade critical to ending plastic pollution – UN News

Global Trade, Plastic Pollution, and the Pursuit of Sustainable Development Goals

Introduction: The Urgent Need for a Global Plastics Treaty

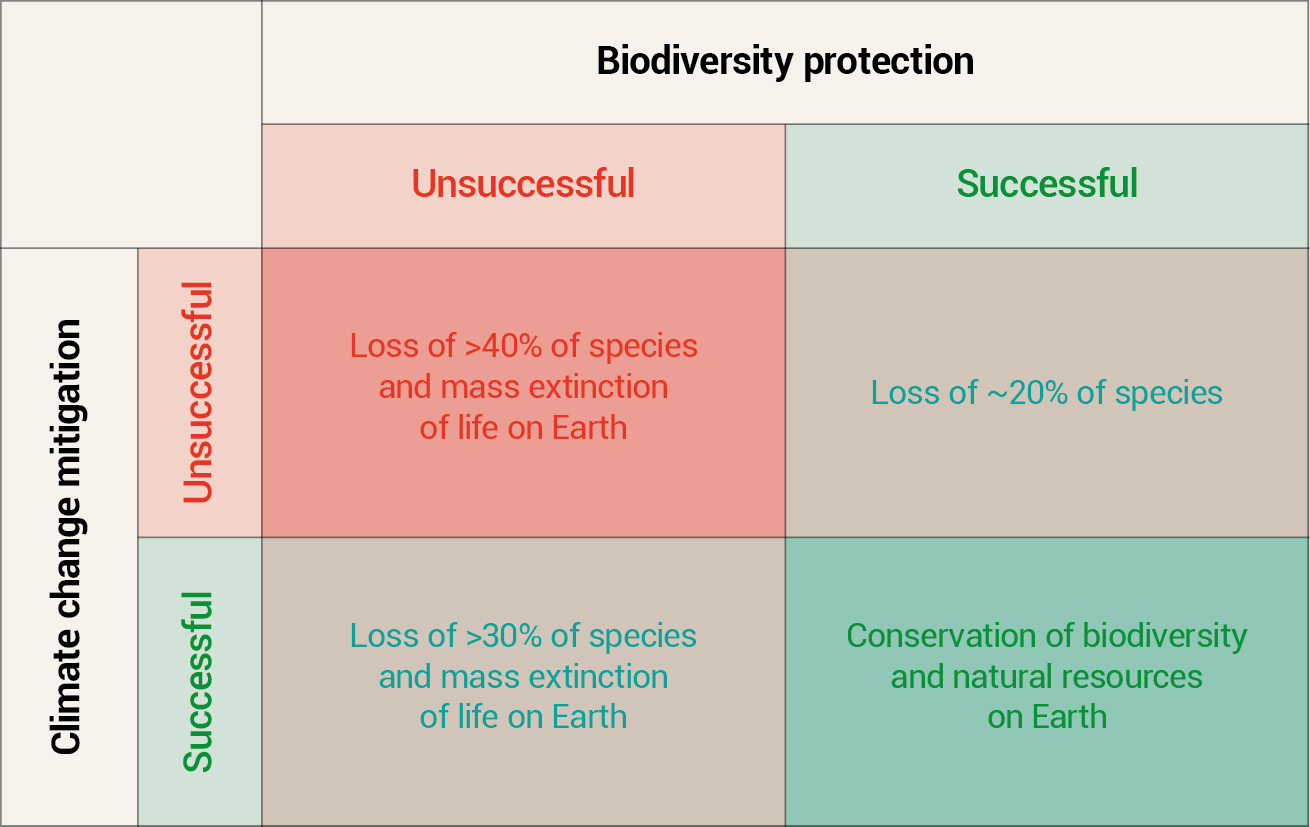

A recent assessment by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) highlights the critical need for a legally binding international instrument to combat plastic pollution. The report underscores that the absence of a comprehensive treaty governing the lifecycle of plastics—from production and trade to disposal—directly impedes progress on several Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The production and waste from plastics contribute significantly to the triple planetary crisis of pollution, biodiversity loss, and climate change, threatening the core objectives of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

The Plastic Crisis: A Barrier to Sustainable Development

Scale of Production and Environmental Impact

The global plastic economy presents a significant challenge to environmental sustainability. In 2023, key figures demonstrated the scale of the issue:

- Plastic production reached 436 million metric tonnes.

- The traded value of plastics exceeded $1.1 trillion, accounting for 5% of total merchandise trade.

- An estimated 75% of all plastics ever produced have become waste.

This immense volume of waste directly undermines SDG 14 (Life Below Water) and SDG 15 (Life on Land), as most discarded plastic pollutes global oceans and terrestrial ecosystems. Furthermore, with 98% of plastics derived from fossil fuels, unchecked production exacerbates climate change, working against SDG 13 (Climate Action).

Disproportionate Impacts on Developing Nations

The consequences of plastic pollution are not evenly distributed. Small island developing states and coastal communities, which have limited capacity for waste management, are particularly vulnerable. This pollution threatens their food systems, economies, and human well-being, creating significant obstacles to achieving SDG 1 (No Poverty), SDG 2 (Zero Hunger), and SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities).

Trade Policy and its Role in Perpetuating the Crisis

Tariff Structures Favoring Plastics

Current global trade policies create an economic environment that favors plastic production over sustainable alternatives, hindering the transition required by SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production). An analysis of tariff structures reveals a significant disparity:

- Tariffs on plastic and rubber products have been reduced over 30 years to an average of 7.2%, making them artificially inexpensive.

- Conversely, ecologically sustainable substitutes such as paper, bamboo, and natural fibres face average tariffs of 14.4%.

This imbalance discourages investment and innovation in sustainable materials, particularly in developing countries aiming to export greener alternatives, thereby limiting progress on SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure).

Fragmented Non-Tariff Measures

While many countries have implemented non-tariff measures like bans and labelling requirements, a lack of international coordination has led to a fragmented regulatory landscape. This inconsistency increases compliance costs and creates barriers for small businesses and exporters in low-income countries, affecting their ability to participate in and benefit from sustainable trade, which is a key target under SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth).

Pathways to a Sustainable Future: A Treaty Aligned with the SDGs

Promoting Ecologically Sustainable Substitutes

UNCTAD advocates for robust support for plastic substitutes derived from natural and renewable sources. The global market for these alternatives is already substantial, reaching $485 billion in 2023, with developing economies showing an annual growth rate of 5.6%. Scaling up this sector is crucial for achieving SDG 12 and fostering green economic growth under SDG 8.

Recommendations for a Comprehensive Plastics Treaty

The ongoing negotiations for a global plastics treaty offer a landmark opportunity to create a framework that supports the entire 2030 Agenda. To be successful, UNCTAD recommends that the treaty incorporate several key elements directly linked to the SDGs:

- Trade Measures for Sustainability: Implement coherent tariff and non-tariff measures that incentivize sustainable substitutes, directly supporting SDG 12 and SDG 9.

- Investment in Circular Infrastructure: Foster investment in waste management and circular economy infrastructure, a critical component of SDG 9 and SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities).

- Digital Traceability: Utilize digital tools to enhance traceability and customs compliance, improving transparency and accountability in line with SDG 12 and SDG 16 (Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions).

- Policy Coherence and Partnerships: Ensure the treaty aligns with frameworks under the WTO, UNFCCC, and the Basel Convention, embodying the spirit of SDG 17 (Partnerships for the Goals) to create a unified global response.

Analysis of the Article in Relation to Sustainable Development Goals

1. Which SDGs are addressed or connected to the issues highlighted in the article?

-

SDG 14: Life Below Water

- The article directly addresses this goal by highlighting that 75% of all plastics produced have become waste, with most ending up in the world’s oceans. This pollution threatens marine ecosystems, which is a core concern of SDG 14.

-

SDG 12: Responsible Consumption and Production

- This goal is central to the article’s theme. The discussion revolves around the entire life cycle of plastics—from production (436 million metric tonnes) and trade ($1.1 trillion) to waste generation. The call for a treaty to govern production, consumption, and disposal, and the promotion of sustainable substitutes, directly aligns with achieving sustainable consumption and production patterns.

-

SDG 13: Climate Action

- The article connects plastic production to climate change by stating that “98 per cent of plastics are derived from fossil fuels, meaning that emissions and environmental damage are expected to rise if left unchecked.” This links the issue of plastic pollution directly to the drivers of climate change, making SDG 13 relevant.

-

SDG 17: Partnerships for the Goals

- The article emphasizes the need for a “legally binding international instrument” and “policy coherence” across organizations like the WTO, UNFCCC, and the Basel Convention. This highlights the importance of global partnerships to tackle a transboundary issue like plastic pollution, which is the essence of SDG 17.

-

SDG 9: Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure

- The call for “investment in waste management and circular infrastructure” and the need to support “ecologically sustainable plastic substitutes” points to SDG 9. This goal focuses on building resilient infrastructure, promoting inclusive and sustainable industrialization, and fostering innovation.

-

SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth

- The article discusses the economic aspects of the plastic industry, including its $1.1 trillion traded value and the impact of inconsistent regulations on “small businesses and low-income exporters.” It also notes the growing market for substitutes ($485 billion), linking environmental sustainability to economic opportunities and challenges.

2. What specific targets under those SDGs can be identified based on the article’s content?

-

Target 14.1: By 2025, prevent and significantly reduce marine pollution of all kinds, in particular from land-based activities, including marine debris and nutrient pollution.

- The article’s focus on the vast amount of plastic waste entering the oceans directly relates to this target of reducing marine debris.

-

Target 12.4: By 2020, achieve the environmentally sound management of chemicals and all wastes throughout their life cycle… and significantly reduce their release to air, water and soil.

- The proposed treaty aims to cover the “entire life cycle of plastics – production, consumption, and waste,” which is the core objective of this target.

-

Target 12.5: By 2030, substantially reduce waste generation through prevention, reduction, recycling and reuse.

- The advocacy for “ecologically sustainable plastic substitutes” and investment in “waste management and circular infrastructure” are strategies aimed at reducing plastic waste generation, aligning with this target.

-

Target 17.10: Promote a universal, rules-based, open, non-discriminatory and equitable multilateral trading system under the World Trade Organization.

- The article points out tariff disparities that make plastics “artificially inexpensive” while hindering trade in sustainable alternatives. Addressing these tariff and non-tariff measures is linked to creating a more equitable trading system.

-

Target 9.4: By 2030, upgrade infrastructure and retrofit industries to make them sustainable, with increased resource-use efficiency and greater adoption of clean and environmentally sound technologies and industrial processes.

- The call to scale up sustainable substitutes and invest in “waste management and circular infrastructure” directly supports the goal of making industries and infrastructure more sustainable.

3. Are there any indicators mentioned or implied in the article that can be used to measure progress towards the identified targets?

- Volume of Plastic Production: The article states that “plastic production reached 436 million metric tonnes worldwide” in 2023. This figure can serve as a baseline indicator to track progress on waste reduction (Target 12.5).

- Traded Value of Plastics and Substitutes: The article provides the traded value of plastics (“surpassing $1.1 trillion”) and their sustainable substitutes (“$485 billion in 2023”). The ratio between these two values can indicate a shift in consumption and production patterns (Target 12.4, Target 9.4).

- Growth Rate of Sustainable Substitutes: The mention of an “annual growth of 5.6 per cent in developing economies” for substitutes is a key performance indicator for the adoption of sustainable alternatives (Target 9.4).

- Tariff Rates: The specific tariff figures cited—”average tariffs of 14.4 per cent” for alternatives versus “7.2 per cent” for plastics—serve as a direct indicator for measuring trade barrier disparities (Target 17.10).

- Percentage of Waste Generation: The statement that “75 per cent of all plastics ever produced have become waste” is a stark indicator of the scale of the pollution problem that needs to be addressed (Target 14.1, Target 12.5).

- Fossil Fuel Dependency: The fact that “98 per cent of plastics are derived from fossil fuels” is an indicator of the industry’s climate impact and can be used to measure progress in decoupling plastic production from fossil fuels (Target 13.2).

4. Table of SDGs, Targets, and Indicators

| SDGs | Targets | Indicators |

|---|---|---|

| SDG 14: Life Below Water | 14.1: Reduce marine pollution and debris. | Percentage of all plastics produced that have become waste (75%). |

| SDG 12: Responsible Consumption and Production | 12.4: Achieve environmentally sound management of waste throughout its life cycle. | Traded value of plastics ($1.1 trillion) vs. substitutes ($485 billion). |

| 12.5: Substantially reduce waste generation. | Annual plastic production volume (436 million metric tonnes). | |

| SDG 13: Climate Action | 13.2: Integrate climate change measures into national policies. | Percentage of plastics derived from fossil fuels (98%). |

| SDG 17: Partnerships for the Goals | 17.10: Promote an equitable multilateral trading system. | Average tariff rates on plastics (7.2%) vs. sustainable alternatives (14.4%). |

| SDG 9: Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure | 9.4: Upgrade infrastructure and industries to be sustainable and adopt clean technologies. | Annual growth rate of trade in sustainable substitutes in developing economies (5.6%). |

Source: news.un.org

What is Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0

;Resize=805#)