Seventh Generation Crisis: ‘Green’ Products For Women Under Fire By PFAS Activists – Science 2.0

Report on Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) in Eco-Labeled Menstrual Products and Implications for Sustainable Development Goals

Introduction and Executive Summary

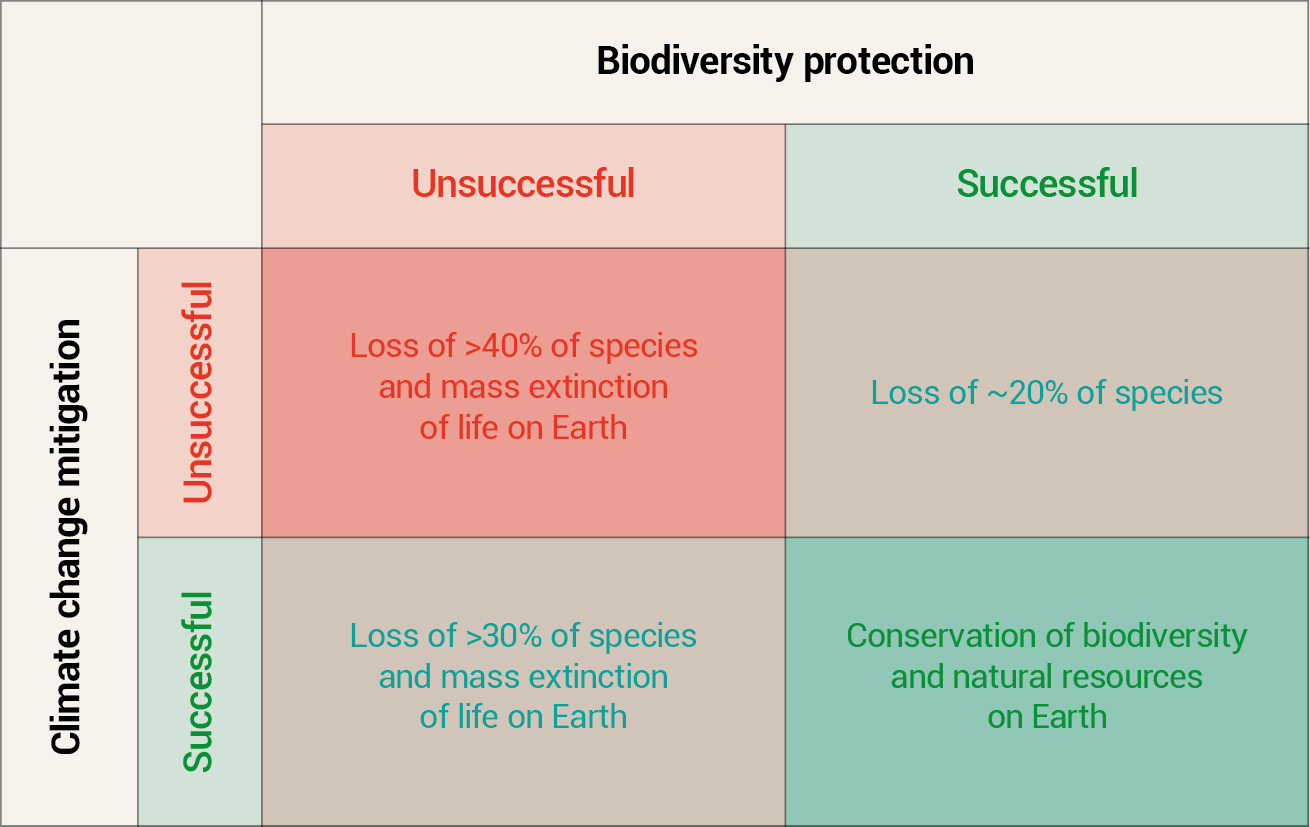

Recent analysis has identified the presence of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), commonly referred to as “forever chemicals,” in consumer products marketed as “green” or “eco-friendly,” including reusable menstrual items. This report examines the findings and their broader implications for public health, environmental integrity, and corporate accountability, framing the issue within the context of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The presence of these substances in products essential for women’s health raises significant concerns related to several SDGs, most notably:

- SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being

- SDG 5: Gender Equality

- SDG 6: Clean Water and Sanitation

- SDG 12: Responsible Consumption and Production

The discourse surrounding these findings involves complex scientific, regulatory, and legal dimensions, highlighting a critical need for policies grounded in robust evidence to protect both human health and the environment.

Analysis of Findings and SDG Linkages

Product Safety and Public Health Concerns (SDG 3)

A study investigating reusable period underwear, sanitary pads, and menstrual cups revealed the presence of PFAS, which are cited as potential endocrine disruptors linked to adverse health outcomes. This directly challenges the objective of SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being), particularly Target 3.9, which aims to substantially reduce the number of deaths and illnesses from hazardous chemicals and air, water, and soil pollution and contamination. The potential for chronic exposure to such chemicals through everyday products undermines consumer safety and public health confidence.

Gender-Specific Impacts and Health Equity (SDG 5)

The products in question are used exclusively by women, making this a critical issue for SDG 5 (Gender Equality). Ensuring that menstrual products are free from harmful chemicals is fundamental to protecting women’s health and upholding their right to safe and effective healthcare products. The lack of transparency and potential health risks associated with these essential items can create barriers to well-being and perpetuate health inequities, conflicting with the principles of gender equality and empowerment.

Environmental Contamination and Water Quality (SDG 6)

The persistence of PFAS means they can leach from products during use or after disposal, entering wastewater systems and contaminating water resources. This poses a direct threat to SDG 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation). Target 6.3 focuses on improving water quality by reducing pollution and eliminating the dumping of hazardous chemicals. The lifecycle of consumer products containing “forever chemicals” contributes to the chemical burden on aquatic ecosystems and drinking water supplies, necessitating a systemic approach to prevent further contamination.

Challenges for Responsible Production and Consumption (SDG 12)

Chemical Management and Corporate Responsibility

The discovery of PFAS in products marketed as “green” highlights a significant gap in achieving SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production). This goal calls for the environmentally sound management of chemicals and wastes throughout their life cycle (Target 12.4) and ensuring that consumers have the relevant information for sustainable lifestyles (Target 12.8).

- Misleading “Green” Claims: The presence of undisclosed PFAS in “eco-friendly” products undermines consumer trust and constitutes a form of “greenwashing,” hindering informed and responsible consumption choices.

- Supply Chain Transparency: Manufacturers must assume greater responsibility for the chemical composition of their products, requiring full transparency and traceability throughout the supply chain.

- Scientific Debate on Risk: A divergence exists between precautionary approaches, often cited in regulatory and legal actions, and traditional toxicological assessments that emphasize dose-response relationships. This debate complicates efforts to establish clear standards for chemical safety. Advanced detection technologies can identify substances at minute concentrations (parts per trillion or lower), challenging regulators to define what constitutes a harmful level of exposure.

Recommendations for Aligning with the 2030 Agenda

To address the challenges posed by PFAS in consumer goods and advance the SDGs, a multi-faceted approach is required:

- Enhance Scientific Research and Data Transparency: Support independent research to clarify the health risks of different PFAS at various exposure levels to provide a solid evidence base for policy, directly supporting SDG 3.

- Strengthen Regulatory Oversight: Develop and enforce clear regulations that restrict or ban non-essential uses of PFAS in consumer products, particularly those for personal care. This aligns with the objectives of SDG 12 and SDG 16 (Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions).

- Promote Authentic Sustainability: Industry must move beyond marketing claims and integrate genuine sustainability principles, including the elimination of hazardous chemicals, into product design and manufacturing. This is essential for achieving SDG 12.

- Empower Consumers: Mandate clear and accurate product labeling to enable consumers to make informed choices, while raising public awareness about the health and environmental impacts of PFAS.

- Foster Multi-Stakeholder Collaboration: Encourage partnerships between scientists, regulators, industry, and civil society organizations to develop holistic and effective solutions, in line with SDG 17 (Partnerships for the Goals).

1. Which SDGs are addressed or connected to the issues highlighted in the article?

The article discusses issues related to several Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by highlighting the health and environmental impacts of chemicals found in consumer products.

-

SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being

The article’s central theme is the potential health risks associated with per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) found in menstrual products. It explicitly mentions that these “endocrine disruptors” are “linked to everything from cancer to decreased fertility to early puberty,” directly connecting to the goal of ensuring healthy lives and promoting well-being.

-

SDG 5: Gender Equality

The analysis specifically focuses on products used by women, such as “period underwear, reusable pads, and menstrual cups,” and states that “women are impacted most.” This highlights a gender-specific health issue, making SDG 5 relevant by addressing challenges that disproportionately affect women’s health and well-being.

-

SDG 6: Clean Water and Sanitation

The article points out that the “Forever Chemicals

are leeching into the water supply.” This directly addresses the concerns of SDG 6, which aims to ensure the availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation, including the prevention of water pollution from hazardous chemicals.

are leeching into the water supply.” This directly addresses the concerns of SDG 6, which aims to ensure the availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation, including the prevention of water pollution from hazardous chemicals.

-

SDG 12: Responsible Consumption and Production

The discussion revolves around “‘Green’ chemical products” and “so-called eco-friendly chemical products” that contain hazardous substances. This relates to the need for sustainable production patterns and the environmentally sound management of chemicals throughout their lifecycle, a core component of SDG 12.

2. What specific targets under those SDGs can be identified based on the article’s content?

Based on the issues raised, the following specific SDG targets can be identified:

-

Target 3.9

“By 2030, substantially reduce the number of deaths and illnesses from hazardous chemicals and air, water and soil pollution and contamination.”

The article’s focus on PFAS as “known endocrine disruptors” linked to severe illnesses like cancer and decreased fertility directly aligns with this target to reduce illness from hazardous chemical contamination.

-

Target 5.6

“Ensure universal access to sexual and reproductive health and reproductive rights…”

While the target is broad, ensuring the safety of menstrual products is a fundamental aspect of menstrual health, which is a key component of sexual and reproductive health for women. The article’s finding of harmful chemicals in these products points to a failure to ensure safe access, making this target relevant.

-

Target 6.3

“By 2030, improve water quality by reducing pollution, eliminating dumping and minimizing release of hazardous chemicals and materials…”

The statement that PFAS are “leeching into the water supply” directly corresponds to this target’s goal of improving water quality by minimizing the release of hazardous chemicals into water systems.

-

Target 12.4

“By 2020, achieve the environmentally sound management of chemicals and all wastes throughout their life cycle… and significantly reduce their release to air, water and soil in order to minimize their adverse impacts on human health and the environment.”

The entire article is a critique of the management of PFAS in consumer goods, including “green” products. It discusses their presence in menstrual products and pizza boxes and their subsequent impact on human health, which is the exact focus of this target.

3. Are there any indicators mentioned or implied in the article that can be used to measure progress towards the identified targets?

The article implies several indicators that could be used to measure progress:

-

Indicator for Target 3.9

The article implies the need to track the incidence of illnesses linked to chemical exposure. It lists “cancer,” “decreased fertility,” and “early puberty” as health outcomes associated with PFAS. Monitoring the rates of these conditions in relation to exposure levels would be an implied indicator.

-

Indicator for Target 6.3

The article directly refers to measuring chemical concentrations in water. Professor Graham Peaslee is quoted as measuring PFAS levels at “parts per million.” This implies a direct indicator: the concentration of PFAS and other hazardous chemicals in the water supply.

-

Indicator for Target 12.4

The study mentioned in the article measured PFAS in menstrual products. This suggests an indicator for responsible production: the concentration of hazardous chemicals (like PFAS) found in consumer products, especially those marketed as “green” or “eco-friendly.”

4. Create a table with three columns titled ‘SDGs, Targets and Indicators” to present the findings from analyzing the article. In this table, list the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), their corresponding targets, and the specific indicators identified in the article.

| SDGs | Targets | Indicators (Identified or Implied in the Article) |

|---|---|---|

| SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being | Target 3.9: Substantially reduce deaths and illnesses from hazardous chemicals and pollution. | Incidence of diseases (e.g., cancer, decreased fertility, early puberty) linked to exposure to hazardous chemicals like PFAS. |

| SDG 5: Gender Equality | Target 5.6: Ensure universal access to sexual and reproductive health. | Presence and concentration of harmful chemicals in menstrual health products. |

| SDG 6: Clean Water and Sanitation | Target 6.3: Improve water quality by reducing pollution and minimizing the release of hazardous chemicals. | Concentration of PFAS in the water supply, measured in parts per million (ppm) or lower. |

| SDG 12: Responsible Consumption and Production | Target 12.4: Achieve the environmentally sound management of chemicals to minimize their adverse impacts on human health. | Concentration of PFAS found in consumer products, including those marketed as “green” or “eco-friendly.” |

Source: science20.com

What is Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0

![Lancaster homeowner’s energy-efficient renovation sparks clash over historic preservation [Lancaster Watchdog] – LancasterOnline](https://bloximages.newyork1.vip.townnews.com/lancasteronline.com/content/tncms/assets/v3/editorial/9/ed/9ed03d32-c902-44d2-a461-78ad888eec38/69050b156baeb.image.png?resize=150,75#)

![Governing Health -Compensation Considerations for Health System Innovation Activities [Podcast] – The National Law Review](https://natlawreview.com/sites/default/files/styles/article_image/public/2025-10/Health AI Security Privacy Data Cyber Medical Doctor-309772690.jpg.webp?itok=i51uHMDx#)