Why are ethnic minority groups falling behind on vaccines? – BBC

Report on Vaccine Uptake Disparities and Sustainable Development Goals in Scotland

Executive Summary

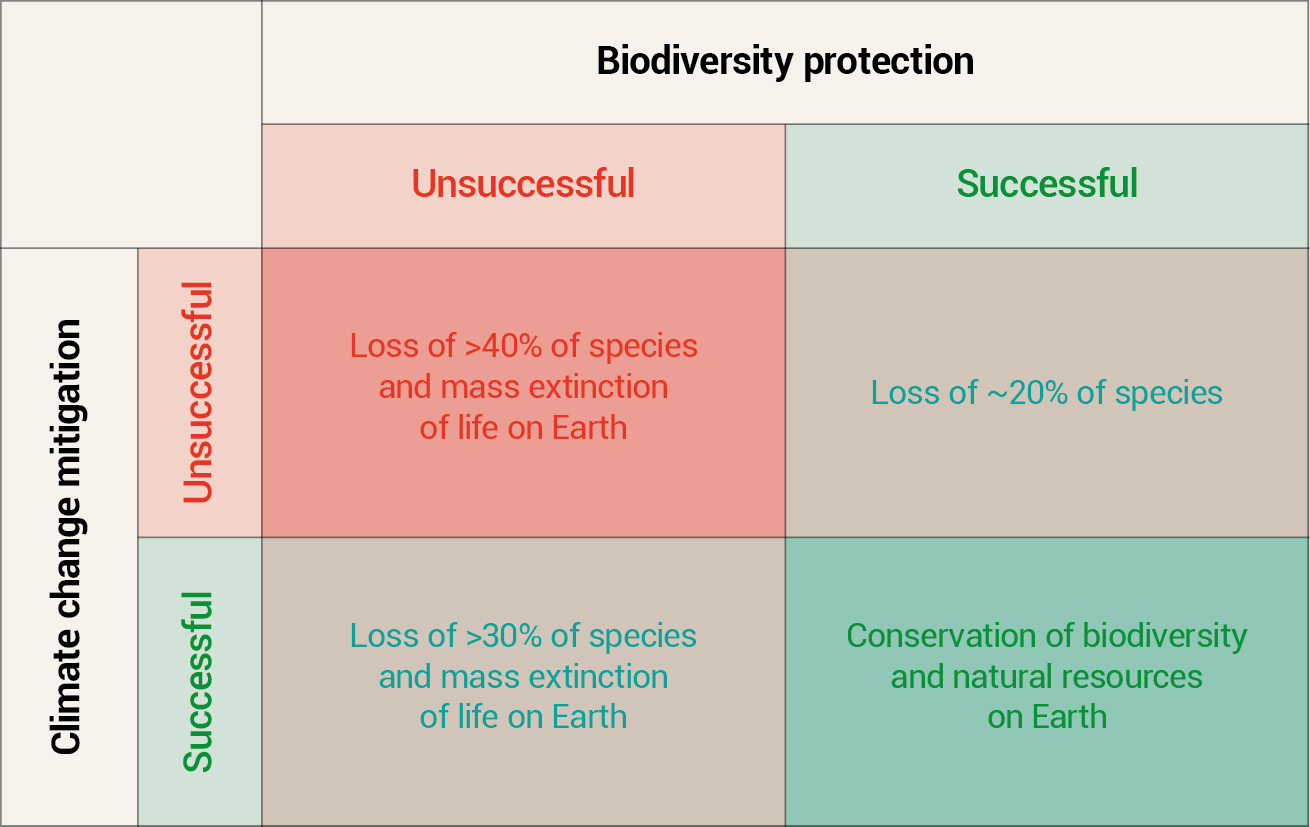

A review of recent data and expert analysis from Scotland reveals significant disparities in vaccine uptake among ethnic minority groups. These inequalities present a substantial challenge to the achievement of key United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being) and SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities). This report synthesizes findings on the scale of the issue, its root causes, and the institutional responses, framing them within the context of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

Analysis of Vaccination Disparities: A Challenge to SDG 3

Recent data, broken down by ethnicity for the first time, indicates that Scotland is struggling to ensure equitable access to and uptake of essential immunisations, directly impacting progress towards SDG 3, which aims to ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages.

MMR Vaccine Uptake and ‘Herd Immunity’

The uptake of the Measles, Mumps, and Rubella (MMR) vaccine highlights a critical public health gap. While overall first-dose rates are near the 95% target set by the World Health Organization for herd immunity, specific communities are falling behind. This disparity jeopardizes the collective progress towards Target 3.3, which seeks to end the epidemics of communicable diseases.

- Almost 25% of children of African descent had not received their second MMR dose by age five.

- Only 75% of children in the African ethnic group received the second dose by age five.

- Uptake for the second dose was 83.8% for children of Caribbean or Black heritage and 87.3% in Asian groups.

Trends Across Other Key Vaccines

The pattern of lower uptake is not isolated to childhood immunisations. It extends to other critical public health programmes, indicating a systemic issue that hinders the achievement of universal health coverage (Target 3.8).

- Human Papillomavirus (HPV): First-dose uptake in the first year of secondary school was 73.7% for the White Scottish group, compared to 57.4% in the Black ethnic group and 53.3% in the Pakistani ethnic group.

- Flu Vaccine: Uptake among eligible adults varied from 55.2% in the White Scottish group to as low as 34.4% in Pakistani groups and 22.6% in Caribbean groups.

- COVID-19: Similar trends of lower uptake were observed during the pandemic.

Investigating Root Causes: Barriers to SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities)

The disparities in health outcomes are a clear manifestation of broader societal inequalities, which SDG 10 aims to reduce. The reasons for vaccine hesitancy are complex and multifaceted, extending beyond individual choice to systemic and institutional failures.

Systemic Issues and Institutional Trust

A foundational barrier is a lack of trust in public institutions, a direct challenge to SDG 16 (Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions). Experts link this mistrust to experiences of racism and discrimination.

- Perceived Discrimination: Dr. Sahira Dar and Dr. Mark Wong highlight that patients from ethnic minority backgrounds report being treated differently and not taken seriously in healthcare settings, leading to delayed diagnoses and poor health outcomes.

- Mistrust in “The System”: Dr. Josephine Adekola’s research found that negative experiences with other public bodies (e.g., immigration, housing, schooling) create a pervasive distrust that extends to healthcare initiatives.

- Official Acknowledgment: Scotland’s Health Secretary has acknowledged racism as a “significant public health challenge,” underscoring the need to enforce non-discriminatory policies as per Target 16.B.

Socio-Cultural and Logistical Barriers

Effective healthcare delivery must be culturally competent and accessible to all, a core principle for achieving SDG 3 and SDG 10.

- Cultural Understanding: Stigma around sexual health can deter uptake of the HPV vaccine in some communities. A lack of cultural awareness, such as the preference for female practitioners among some Muslim women, can create access barriers.

- Logistical Hurdles: Research from the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH) indicates that practical issues, such as the timing and location of appointments, are significant barriers for many families who wish to vaccinate.

- Misinformation: The spread of misinformation, often from trusted international family networks, creates additional confusion and hesitancy. Conspiracy theories and false claims specifically targeting ethnic or religious groups were noted during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Critical Role of Data for SDG Monitoring

The principle of “leaving no one behind” requires robust data to identify and support the most vulnerable populations. The historical lack of ethnicity data in Scottish health reporting has been a significant obstacle to addressing inequalities, a key component of SDG 17 (Partnerships for the Goals).

Addressing the Ethnicity Data Gap

Dr. Mark Wong identified a “missed opportunity” at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic to collect ethnicity data, which initially made it difficult to prove the disproportionate impact on minority communities in Scotland. This gap hindered the development of targeted, evidence-based interventions required by Target 17.18 (enhance capacity-building support… to increase significantly the availability of high-quality, timely and reliable data disaggregated by… race, ethnicity…).

A Turning Point in Public Health Strategy

The introduction of ethnicity data collection for vaccination programmes since November 2021 is described as a “turning point.” This development is fundamental for monitoring health inequalities, designing effective public health messaging, and holding institutions accountable for achieving equitable outcomes in line with the SDGs.

Strategic Responses and Path Forward

Official Commitments

Public bodies have acknowledged the challenge and stated their commitment to addressing it.

- Scottish Government: A spokesperson affirmed that the national immunisation programme will continue to focus on increasing uptake, building community confidence, and reducing health inequalities.

- Public Health Scotland (PHS): A statement recognised the declines in uptake and “persistent health inequalities that leave some communities more vulnerable than others.” PHS has introduced measures like an MMR “status check” in secondary schools to catch up on missed doses.

Conclusion and Recommendations

To effectively address vaccine disparities and advance the Sustainable Development Goals, a multi-stakeholder approach is required. Based on the expert analysis, key actions should focus on:

- Building Trust (SDG 16): Proactively engage with community leaders and organisations to rebuild trust in public health institutions.

- Combating Racism (SDG 10): Implement and enforce anti-racism policies within the healthcare system to ensure all patients are treated with dignity and respect.

- Improving Accessibility (SDG 3): Offer flexible, accessible, and culturally sensitive vaccination services that address the logistical and cultural barriers faced by communities.

- Enhancing Data Utilisation (SDG 17): Continue to collect and analyse disaggregated data to monitor inequalities and inform targeted public health strategies.

Analysis of SDGs in the Article

1. Which SDGs are addressed or connected to the issues highlighted in the article?

-

SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being

- The article’s primary focus is on public health, specifically the uptake of vaccines for communicable diseases like Measles, Mumps, Rubella (MMR), Covid-19, flu, and HPV. It discusses the importance of vaccination for preventing disease and achieving “herd immunity,” directly aligning with the goal of ensuring healthy lives for all.

-

SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities

- A central theme of the article is the disparity in health outcomes and vaccine coverage among different ethnic groups in Scotland. It explicitly states there is a “growing disparity in vaccine uptake among some ethnic minority groups” and attributes this to systemic issues like racism and discrimination, which is the core focus of SDG 10.

-

SDG 16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions

- The article highlights a “lack of trust in organisations promoting the vaccine” and an “overall distrust in ‘the system'” among minority communities. This distrust is linked to experiences of discrimination and ineffective public health messaging, pointing to a need for more effective, accountable, and inclusive public institutions as promoted by SDG 16.

2. What specific targets under those SDGs can be identified based on the article’s content?

-

Targets for SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being)

- Target 3.3: End the epidemics of communicable diseases. The article directly relates to this by discussing efforts to increase vaccination against measles, flu, and HPV to prevent outbreaks. The mention that “Measles cases have been increasing across Scotland” underscores the urgency of this target.

- Target 3.8: Achieve universal health coverage, including access to quality essential health-care services and access to safe, effective, quality and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all. The article demonstrates that universal access is not being fully achieved, as ethnic minorities face barriers such as “the timing and location of vaccine appointments” and a lack of culturally appropriate services, leading to lower vaccine uptake.

-

Targets for SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities)

- Target 10.2: Empower and promote the social, economic and political inclusion of all, irrespective of race, ethnicity, or other status. The article shows how health inequalities are a form of exclusion, with lower vaccine rates for African, Caribbean, Black, and Asian groups preventing them from receiving the same level of health protection as the majority population.

- Target 10.3: Ensure equal opportunity and reduce inequalities of outcome, including by eliminating discriminatory policies and practices. The article directly links lower vaccine uptake to systemic issues, quoting experts who believe “racism is the key reason for poorer health outcomes.” It also references the Scottish Health Secretary’s acknowledgement of racism as a “significant public health challenge” that must be combatted.

-

Targets for SDG 16 (Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions)

- Target 16.6: Develop effective, accountable and transparent institutions at all levels. The reported “distrust in this community” towards public bodies and the healthcare system indicates a perceived lack of effectiveness and accountability. The initial “ethnicity data gap” also points to a lack of transparency in monitoring health outcomes.

- Target 16.7: Ensure responsive, inclusive, participatory and representative decision-making at all levels. The article notes that “public health messaging not effectively reaching or convincing minority ethnic communities” and the lack of “information that is culturally and linguistically appropriate” are key problems, highlighting a failure of institutions to be responsive and inclusive.

3. Are there any indicators mentioned or implied in the article that can be used to measure progress towards the identified targets?

Yes, the article mentions several explicit and implied indicators:

-

Explicit Quantitative Indicators

- Vaccination Coverage Rates: The article provides specific data points that can be used to measure progress. For example:

- MMR second dose uptake by age five: “Only 75% of children in the African ethnic group received the second dose.”

- Flu vaccine uptake among eligible adults: “uptake varies from 55.2% in the White Scottish group, down to… only 22.6% in the Caribbean groups.”

- HPV vaccine uptake in first-year secondary school: “73.7%” for the White Scottish group versus “57.4% in the Black ethnic group and (53.3%) in the Pakistani ethnic group.”

- Benchmark Targets: The article mentions the “World Health Organization (WHO) target of 95%” for MMR vaccination, providing a clear benchmark against which to measure national and sub-group performance.

- Vaccination Coverage Rates: The article provides specific data points that can be used to measure progress. For example:

-

Implied Qualitative and Process Indicators

- Prevalence of Discrimination in Healthcare: While not quantified, the article implies this is a key metric through statements like “patients from these groups are treated differently” and “people from minority ethnic backgrounds are not taken seriously when in healthcare settings.”

- Public Trust in Institutions: Progress could be measured by tracking the level of trust in the healthcare system among ethnic minorities. The article implies this is currently low, citing a “lack of trust in organisations promoting the vaccine” and an “overall distrust in ‘the system’.”

- Availability of Disaggregated Data: The article highlights the importance of the “ethnicity data gap” and describes the recent introduction of ethnicity data collection for vaccines as a “turning point.” The continued collection and use of such data is a key process indicator.

- Accessibility and Cultural Appropriateness of Services: Progress can be measured by assessing whether barriers like “inflexible vaccine appointments” and the lack of “culturally and linguistically appropriate” information have been addressed.

4. Summary Table of SDGs, Targets, and Indicators

| SDGs | Targets | Indicators Identified in the Article |

|---|---|---|

| SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being |

3.3: End epidemics of communicable diseases.

3.8: Achieve universal health coverage and access to essential medicines and vaccines for all. |

|

| SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities |

10.2: Promote social inclusion of all, irrespective of ethnicity.

10.3: Ensure equal opportunity and reduce inequalities of outcome by eliminating discriminatory practices. |

|

| SDG 16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions |

16.6: Develop effective, accountable, and transparent institutions.

16.7: Ensure responsive, inclusive, and representative decision-making. |

|

Source: bbc.com

What is Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0