The Growing Danger of Dams

The article highlights the parallels between dams and fossil fuels, as both have provided short-term benefits while concealing long-term environmental liabilities. It emphasizes the need to recognize the true costs of such infrastructure, which can lead to devastating consequences, as witnessed in the Libyan dam collapses.

The collapse of two Libyan dams earlier this month is likely to herald a grim new dam era, in which the decline of dam building accelerates and deadly dam failures become more and more common. The consequences could be catastrophic for millions of people.

Triggered by intense rainfall from a climate-change-supercharged Mediterranean cyclone, the Libyan dam collapses released floodwater that deposited a portion of the city of Derna in the Mediterranean Sea, drowned thousands of people, displaced tens of thousands more, and has left nearly 300,000 children at increased risk of disease and malnutrition. Just as unprecedented fires, floods, and storms this year have introduced many people to the dangers of climate change, the immensity of the Derna tragedy has focused attention on the unappreciated risks that dams pose.

The dam-building industry was already in decline long before the Derna disaster. “Peak dams,” the moment when dam-building began to ebb, is now believed to have occurred at least a decade ago. “There will not be another ‘dam revolution’ to match the scale of the high-intensity dam construction experienced in the early to middle 20th century,” proclaimed a 2021 United Nations University study. It found that global construction of large dams fell from about 1,500 a year in the late 1970s to about 50 a year in 2020. In Africa, the continent with the highest remaining hydropower potential, a study published in Science last month concluded that the decreasing cost of wind and solar energy will make hydroelectric dams non-competitive by 2030.

The increasing danger of dams stems in part from a simple fact: they are aging. Most of the world’s dams were built before 1985 and are either approaching or have passed the point when they need substantial repair, which is about 50 years old. Yet few are being repaired. In the U.S., where the average dam is 65 years old, the dangers have been well-documented for decades yet barely heeded. In 2021, the American Society of Civil Engineers issued an infrastructure “report card” on which U.S. dams were given a grade of “D”— the same grade dams have received in every ASCE report card since the first in 1998.

A February 2023 study by the Association of State Dam Safety Officials estimated that rehabilitating 65,000 of the U.S.’s large- and medium-sized dams would cost $157.5 billion—a price tag that will continue to mount as repair work is deferred. And a 2022 Associated Press analysis identified 2,200 U.S. dams that need repairs and would threaten downstream populations if they fail. State and federal funding for repairs has been increasing but nowhere near the amount needed to ensure safety. Politicians once took delight in a new dam’s ribbon-cutting, but they have always shown far less interest in providing funding for the un-sexy job of dam maintenance.

In other countries, where government budgets are far more strained than in the U.S., the situation is much worse. In Libya, the failing dams’ weaknesses were well-known. A study of the two dams published last year presciently warned that “immediate measures must be taken for regular maintenance… because in the event of a huge flood, the result will be disastrous” for downstream residents. One reason repairs didn’t take place is that Libya is still reeling from the 2014-2020 civil war and is plagued by two rival administrations. In fact, according to a report last week in Foreign Policy, more than $2 million was allocated for maintenance of the two dams in 2012 and 2013, but no work ever took place. Libya is one of dozens of countries where dysfunction stymies dam maintenance.

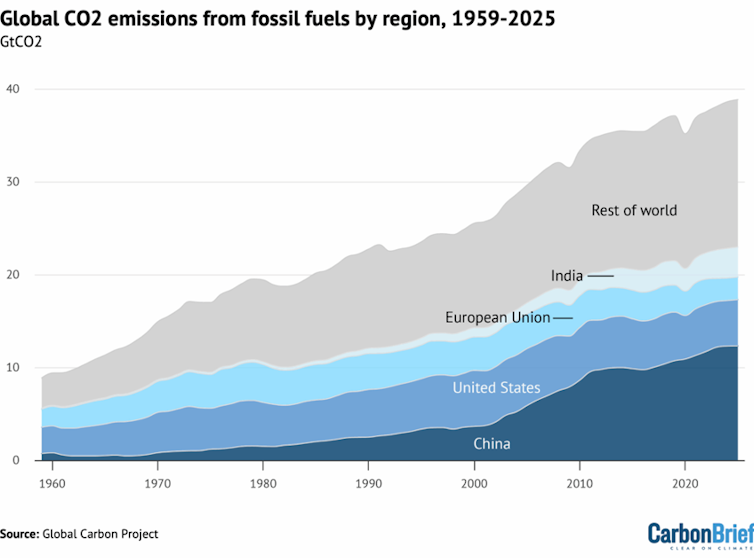

Climate change also makes dam collapse more likely. The design of virtually all the world’s large dams was based on hydrological records that were often insufficient to begin with and certainly didn’t take climate change into account. Now, not only are those records out-of-date, but the huge variability that climate change has introduced into precipitation levels complicates all dam planning. By making both extended droughts and unprecedented floods more frequent, climate change has forced reductions and even stoppages of hydropower generation of some dams, while also subjecting many to floods bigger than they were designed to withstand. Floods presumed to occur once in 1,000 years may now happen once or twice a decade. On top of all this, as climate change intensifies, it will generate even bigger storms and floods.

The risk that dams pose to humans can be partially offset by more carefully monitoring weather forecasts, releasing water behind dams if necessary, and installing warning systems that alert imperiled people of the need to evacuate.

But the best way to eliminate the danger is to remove dams entirely. This is especially true for older dams, whose reservoirs become filled with sediment that displaces water and reduces their effectiveness as electricity generators and water storers—and removal often costs less than repairs. Yet dam removal is still in its infancy. Out of the U.S.’s several million dams of all sizes, about 2,000 mostly small dams have been dismantled. Still, the movement is gaining momentum in the U.S. and Europe.

Removal’s greatest benefit is environmental: in returning rivers to free-flowing conditions, it reunites rivers with their floodplains, restores riparian habitat, improves water quality, and re-enables circulation of migrating fish.

Removal also reduces greenhouse gas emissions. The idea that dams are “clean” is a widespread misconception, still endlessly promoted by international dam builders and sometimes cited erroneously even by environmentalists. But reservoirs—particularly in tropical and sub-tropical regions—emit methane, sometimes copiously, mostly as a byproduct of decomposing plants and other organic matter near reservoir bottoms. A 2021 study in Global Biochemical Cycles found that the world’s reservoirs emit every year the equivalent of more than a gigaton of carbon dioxide—more greenhouse gas than Germany, the world’s sixth largest emitter.

As dams’ immense environmental damage has surfaced in recent decades, it has become apparent that dams and fossil fuels share many of the same attributes. For a time both delivered a bounty that transformed the world, while their environmental liabilities were hidden. They’re poster children for the seductive allures of technology and its transience—of top-down, growth-at-all-costs economic development and the illusion that humans are exempt from nature’s dominion. Now we measure their costs in bodies swept out to sea.

What is Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0