The social costs of solar radiation management – Nature

Executive Summary

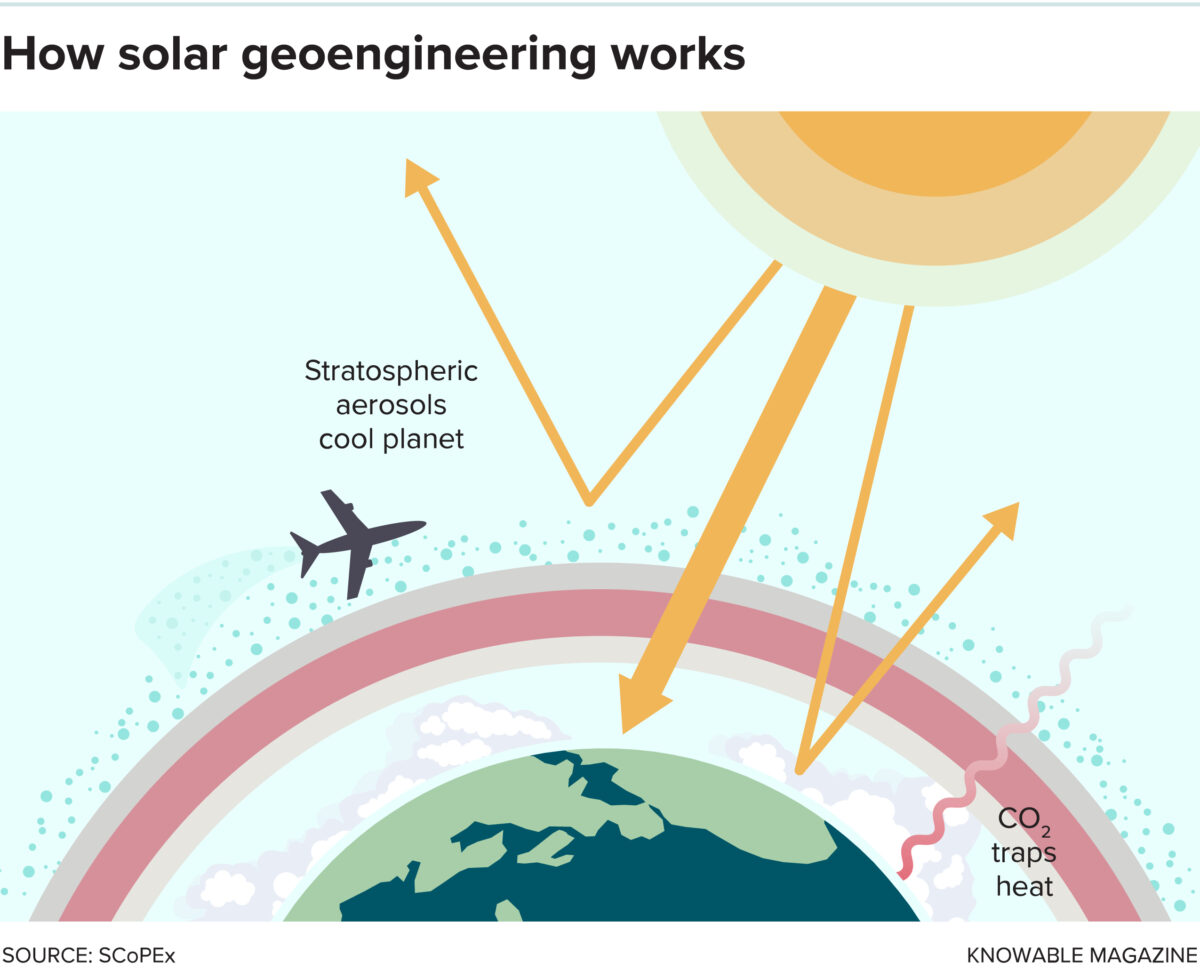

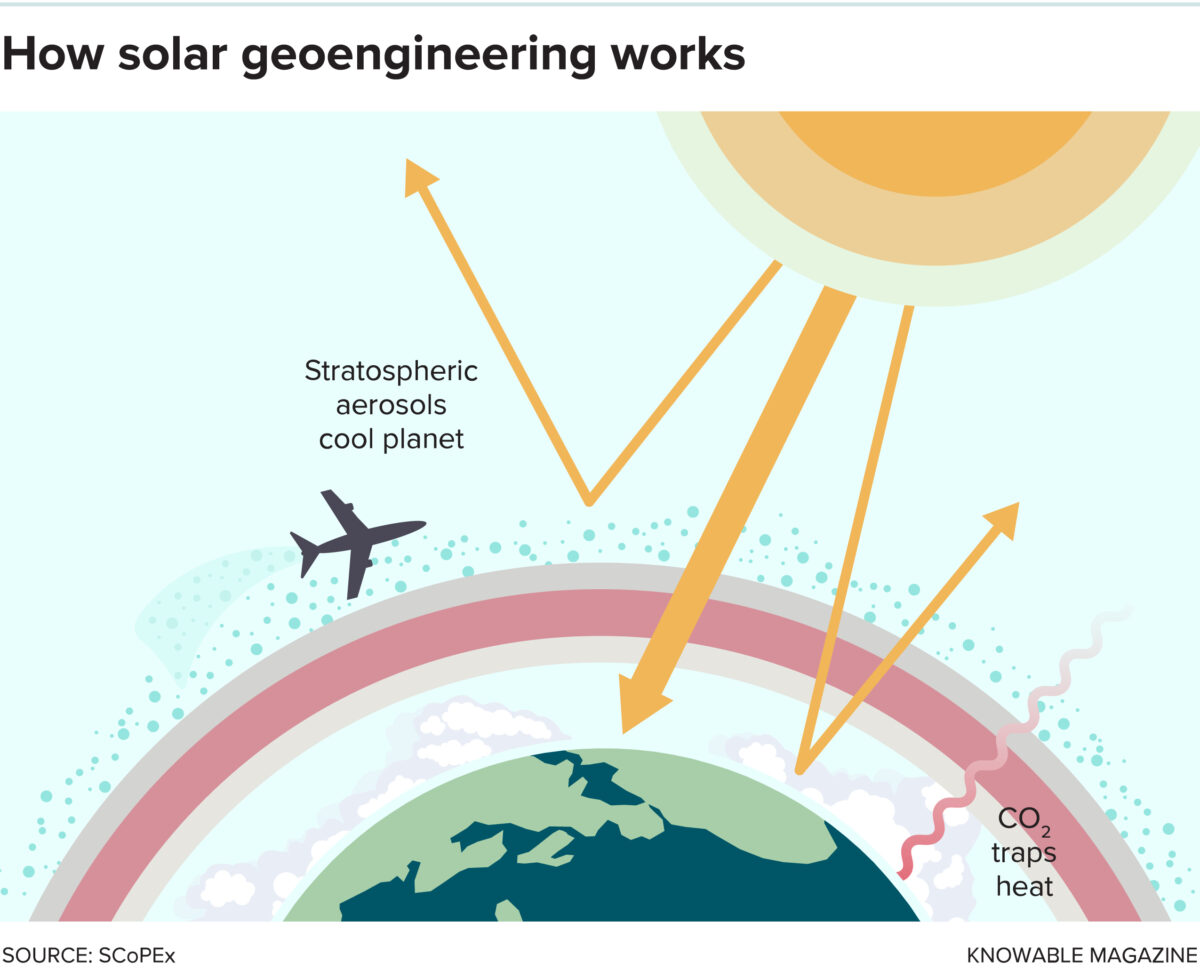

This report provides a holistic analysis of the costs and risks associated with Solar Radiation Management (SRM) as a climate intervention strategy, with a significant emphasis on its alignment with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). While the direct technical costs of SRM technologies like Stratospheric Aerosol Injection (SAI) and Marine Cloud Brightening (MCB) appear modest, a comprehensive assessment reveals substantial hidden costs and profound risks. These challenges threaten to undermine global progress on key SDGs, including those related to poverty, hunger, inequality, climate action, and peace.

The analysis identifies four primary categories of risk associated with SRM:

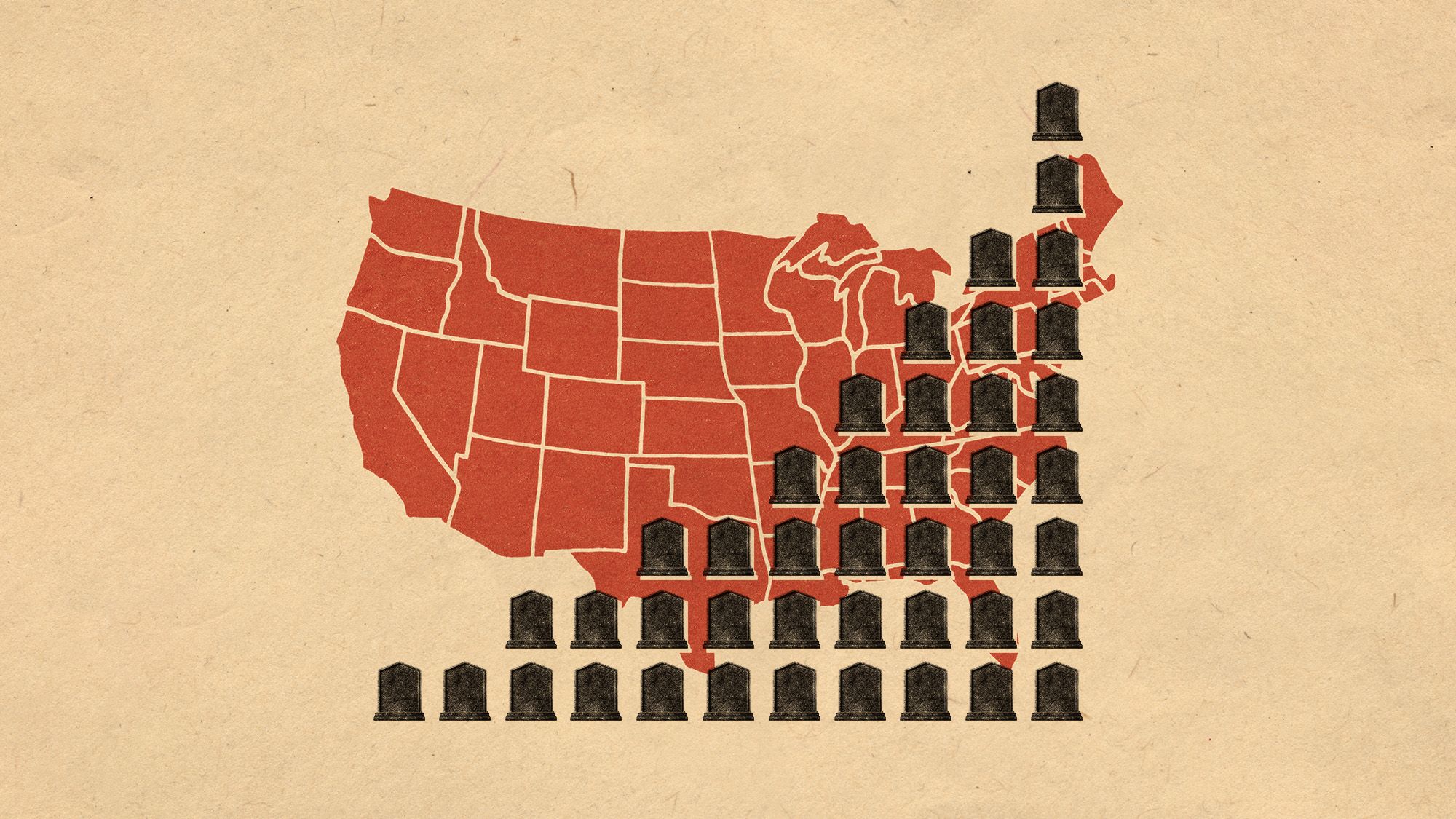

- Side-Effect Harms: SRM is projected to cause significant, unevenly distributed climatic changes, creating regional winners and losers. The resulting harms, estimated to cost up to $809 billion annually in compensation, would disproportionately affect vulnerable nations, directly contravening SDG 1 (No Poverty), SDG 2 (Zero Hunger), and SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities).

- International Political Challenges: The global and transboundary nature of SRM necessitates unprecedented international consensus for governance. The high potential for disagreement over deployment, control, and compensation creates a significant risk of geopolitical instability, undermining SDG 16 (Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions) and SDG 17 (Partnerships for the Goals).

- Domestic Political Unfeasibility: The attribution of any adverse weather event to SRM interventions creates a unique and perilous political risk for national leaders, potentially making the technology too volatile for the sustained, long-term deployment required to meet SDG 13 (Climate Action).

- Termination Risk: A sudden cessation of SRM deployment could trigger rapid and catastrophic global warming, posing an existential threat to ecosystems and human societies, and jeopardizing the entire 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

In comparison, Large-Scale Carbon Dioxide Removal (LCDR) presents a different risk profile. While technically more expensive, LCDR addresses the root cause of climate change by removing atmospheric CO2. It poses fewer risks to global stability and requires a more manageable level of international cooperation. This report concludes that when the full spectrum of social, political, and ethical costs is considered, the viability of SRM as a sustainable climate solution is highly questionable, and the comparison with LCDR becomes far more complex than a simple analysis of technical costs would suggest.

1.0 Introduction: Climate Intervention and the Sustainable Development Goals

The persistent failure of multilateral emissions treaties to curb the rise in global carbon dioxide levels has intensified the search for supplemental climate intervention solutions. Historically categorized as “geoengineering,” these interventions fall into two distinct classes: Solar Radiation Management (SRM), which aims to reflect solar energy back into space, and Carbon Dioxide Removal (CDR), which seeks to extract and store atmospheric CO2. This report evaluates the true, all-things-considered cost of SRM, moving beyond narrow technical estimates to incorporate its profound implications for the Sustainable Development Goals.

While SRM is often promoted for its low deployment cost, this perspective overlooks critical socio-political and ethical dimensions that directly impact the global community’s ability to achieve a sustainable future. This analysis frames the challenges of SRM within the context of the SDGs to provide a more complete understanding of its potential consequences.

2.0 Analysis of Solar Radiation Management (SRM) and its Implications for SDGs

2.1 Side-Effect Harms and Socio-Economic Costs

SRM deployment would intentionally alter the global climate system, but its cooling effects would not be uniform. This variance will inevitably create regions that are made worse off, experiencing adverse effects such as droughts or floods that would not have occurred otherwise. This outcome has severe implications for several SDGs.

- Impact on SDGs 1, 2, and 10: The side-effect harms from SRM are likely to be most pronounced in tropical regions and the Global South, areas already highly vulnerable to climate change. By potentially exacerbating droughts in Sub-Sahelian Africa or altering monsoon patterns, SRM could devastate agricultural systems and local economies. This would directly undermine SDG 1 (No Poverty) and SDG 2 (Zero Hunger), while widening the gap between nations and thus violating the core principle of SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities).

- Compensation and Justice (SDG 16): The moral and legal duty to compensate the “losers” of SRM presents a monumental challenge. This report estimates the potential annual liability for SAI alone could range from $0 to $809 billion. Establishing a fair and functional global compensation mechanism is fraught with difficulty, as evidenced by the persistent struggles of the UN’s “loss and damage” fund. A failure to provide adequate compensation would represent a profound global injustice, undermining the principles of SDG 16 (Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions).

- Ecological and Health Risks (SDGs 3, 14, 15): Beyond temperature and precipitation, SRM poses other risks, such as potential ozone layer depletion from SAI. This would increase harmful UV radiation, threatening human health (SDG 3) and terrestrial ecosystems (SDG 15). Marine Cloud Brightening (MCB) directly manipulates marine environments, with unknown consequences for marine life (SDG 14).

2.2 Geopolitical Instability and Governance Challenges

Because SRM affects the entire planet, its deployment requires a global system of governance built on unprecedented international cooperation. The political obstacles to creating such a system are immense and pose a direct threat to global peace and stability.

- Erosion of Global Partnerships (SDGs 16 & 17): Achieving consensus on whether, how, and at what level to deploy SRM would be a contentious process. Nations would likely negotiate from self-interest, with disagreements over the “optimal” global temperature and compensation for harms. Powerful states might resist delegating authority to a global body, while geopolitical adversaries would be unlikely to cede control over their climate. This dynamic threatens to create deep global divisions, directly opposing the collaborative spirit of SDG 17 (Partnerships for the Goals) and risking conflicts that would destabilize the international order, a core concern of SDG 16.

- Risk of Unilateral Action: The low technical cost of SRM raises the possibility of unilateral deployment by a single state or a small coalition. Such an act, undertaken without global consent, would be perceived as an aggressive infringement on the sovereignty of all other nations and could provoke severe countermeasures, ranging from sanctions to military conflict. This scenario represents a catastrophic failure of the international cooperation envisioned in the SDGs.

2.3 Domestic Political Feasibility

SRM’s nature as an artificial intervention in the climate system creates a unique political risk profile for domestic leaders. By supporting SRM, politicians would effectively take ownership of the weather, making them accountable for every drought, flood, or storm. This political fragility makes SRM an unreliable long-term strategy for achieving SDG 13 (Climate Action), as public support could evaporate with the first bout of “bad” weather or in response to populist campaigns against “playing God.” The political opposition already forming in Europe, Mexico, and parts of Africa indicates that securing the stable, multi-generational political will needed for SRM is highly improbable.

2.4 Mitigation Deterrence and Termination Risks

The promise of a “cheap fix” from SRM could disincentivize the difficult but necessary work of reducing carbon emissions, thereby undermining the primary objective of SDG 13 (Climate Action). This sets the stage for the most significant risk of all: termination shock. If SRM were deployed for decades while CO2 levels continued to rise, a sudden halt—due to war, political collapse, or technical failure—would cause global temperatures to skyrocket at a rate far exceeding current warming. The resulting climate chaos would be catastrophic for all human and natural systems, rendering the pursuit of any Sustainable Development Goal impossible.

3.0 Comparative Analysis: Large-Scale Carbon Dioxide Removal (LCDR)

When the holistic costs of SRM are considered, the comparison with an ambitious program of Large-Scale Carbon Dioxide Removal (LCDR) becomes more nuanced. While not a panacea, LCDR offers a different profile of costs and benefits with respect to the SDGs.

3.1 Economic and Technical Profile

LCDR is significantly more expensive in technical terms, with estimates approaching $1 trillion annually to remove a quarter of current emissions. However, these costs must be weighed against SRM’s massive potential liabilities for side-effect harms. Furthermore, public investment in LCDR could drive innovation and create employment, contributing positively to SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) and SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure). It must be noted, however, that LCDR carries its own sustainability risks related to land, water, and energy use, which require careful management to avoid negative impacts on SDG 2 (Zero Hunger), SDG 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation), and SDG 15 (Life on Land).

3.2 Governance and Political Profile

LCDR is politically and institutionally more feasible than SRM. Its governance could be managed by a consortium of contributing developed nations without requiring universal global consent, making it more compatible with the partnership models of SDG 17. Because it does not infringe on the sovereignty of non-participating nations, it is far less likely to provoke the geopolitical conflict that threatens SDG 16. Domestically, it is less controversial as it involves removing a pollutant rather than adding one.

3.3 Climate System Integrity (SDG 13)

Crucially, LCDR addresses the root cause of climate change by reducing atmospheric CO2 concentrations. It does not mask the warming effect of greenhouse gases and therefore carries no risk of termination shock. This makes it a fundamentally more stable and reliable approach for achieving the long-term goals of SDG 13 (Climate Action).

4.0 Conclusion

An evaluation of Solar Radiation Management limited to its technical costs is dangerously incomplete. When the full spectrum of social, political, and ethical risks is analyzed through the lens of the Sustainable Development Goals, SRM is revealed to be a high-risk strategy that could actively undermine global progress.

The key findings of this report are:

- The side-effect harms of SRM threaten to exacerbate poverty and inequality, directly conflicting with SDGs 1, 2, and 10.

- The governance requirements for SRM are so demanding that they risk provoking international conflict, jeopardizing SDGs 16 and 17.

- The risk of termination shock poses a catastrophic threat to the entire 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

- Large-Scale Carbon Dioxide Removal, while financially costly, presents a more stable and politically feasible path that is better aligned with the principles of sustainable development.

Therefore, any consideration of climate intervention must move beyond simplistic economic calculations to a holistic assessment of how these powerful technologies align with the global commitment to a just, peaceful, and sustainable future. The profound risks SRM poses to the SDGs suggest that it is not a viable or responsible solution to the climate crisis.

1. Which SDGs are addressed or connected to the issues highlighted in the article?

Explanation of Relevant SDGs

The article on the social costs of Solar Radiation Management (SRM) and its comparison with Carbon Dioxide Removal (CDR) touches upon several Sustainable Development Goals. The analysis of climate intervention technologies inherently involves environmental, economic, social, and political dimensions that are central to the SDGs.

- SDG 13: Climate Action

This is the most central SDG to the article. The entire text revolves around proposed solutions (SRM and CDR) to combat climate change, which is the core of SDG 13. The article discusses the failure of existing climate policies (“Multilateral emissions treaties have proven to be an inadequate response to climate change”) and evaluates alternative climate intervention strategies to mitigate global warming. - SDG 16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions

The article extensively discusses the governance challenges of SRM. It highlights that SRM “would depend on unprecedented international cooperation and consensus and, as a result, risk global instability.” The need for global governance, the potential for conflict over side-effect harms, the failure of international negotiations (e.g., at the UN Environment Assembly), and the call for fair compensation mechanisms directly relate to building effective, accountable, and inclusive institutions and ensuring justice. - SDG 17: Partnerships for the Goals

This goal is crucial to the article’s discussion on international cooperation. The text argues that SRM “demands the involvement of every nation on Earth and a globally coordinated system of governance.” It also proposes an alternative model for Large-Scale CDR (LCDR) “administered by a consortium of developed states,” which is a clear example of a multi-stakeholder partnership to achieve a sustainable development outcome. - SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities

The article emphasizes the unequal distribution of SRM’s impacts, noting that it will likely “harm 0% to 7% of the world’s population as a side-effect,” with these effects being “most pronounced in South America and Sub-Sahel Africa.” This raises issues of inequality between nations (inter-country inequality). The discussion on the “duty to compensate the net losers” and the failure of “corrective justice in the climate context” directly addresses the need to reduce inequalities. - SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth

The economic implications of climate change and its proposed solutions are a major theme. The article quantifies the potential economic damages of unmitigated climate change (“a 10% loss in global GDP”), the costs of SRM side-effects (“between $0 and $809 billion annually”), and the massive public spending required for LCDR (“$950 billion a year”). This analysis of economic costs and benefits directly relates to sustainable economic growth. - SDG 9: Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure

The article is fundamentally about large-scale technological innovation. It analyzes advanced technologies like Stratospheric Aerosol Injection (SAI), Marine Cloud Brightening (MCB), Direct Air Capture (DAC), and Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage (BECCS). It discusses the need to enhance scientific research to lower costs (e.g., the “Carbon Negative Shot” program aiming for DAC costs “below $100 per ton”) and build new infrastructure for deployment. - SDG 2: Zero Hunger & SDG 15: Life on Land

The potential negative side-effects of climate interventions on ecosystems and food systems are mentioned. The article notes that SRM could cause “novel risks of floods or droughts,” impacting agriculture. Furthermore, it states that large-scale CDR could lead to “biodiversity loss and food insecurity, especially as a result of land-based approaches.” - SDG 14: Life Below Water

The article mentions Marine Cloud Brightening (MCB) and its potential application in “saving their coral reefs,” which directly connects to the goal of conserving and sustainably using marine resources.

2. What specific targets under those SDGs can be identified based on the article’s content?

Identified SDG Targets

Based on the article’s content, several specific SDG targets can be identified as directly relevant to the discussion.

- Target 13.1: Strengthen resilience and adaptive capacity to climate-related hazards and natural disasters in all countries.

The article discusses how SRM and CDR are proposed to moderate “key climate hazards” but also warns that SRM could create new risks, such as “novel risks of floods or droughts” in certain regions, which would impact resilience. - Target 13.2: Integrate climate change measures into national policies, strategies and planning.

The entire essay is a high-level analysis of integrating climate intervention technologies (SRM, CDR) into global climate strategy as a supplement to failing emissions treaties. - Target 13.a: Implement the commitment undertaken by developed-country parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change to a goal of mobilizing jointly $100 billion annually…

The article references the failure of climate finance mechanisms, citing the “loss and damage” fund established at COP27, where “less than $750 million had been pledged—far short of expectations,” highlighting shortcomings in financial commitments. - Target 16.6: Develop effective, accountable and transparent institutions at all levels.

The article’s focus on the need for a “globally coordinated system of governance” for SRM and the critique of its political feasibility directly address the challenge of creating effective and accountable global institutions. - Target 16.8: Broaden and strengthen the participation of developing countries in the institutions of global governance.

The text points out that SRM’s side effects are most pronounced in the “global South” and that the failure to establish fair compensation mechanisms reflects a lack of influence for developing nations in global climate justice. - Target 17.16: Enhance the global partnership for sustainable development, complemented by multi-stakeholder partnerships…

The article critiques the current state of global partnerships on climate (“Multilateral emissions treaties have proven to be an inadequate response”) and proposes new partnership models, such as an LCDR program “administered by a consortium of developed states.” - Target 9.5: Enhance scientific research, upgrade the technological capabilities of industrial sectors in all countries…

The article discusses the need for technological advancement to make CDR viable, referencing the US Department of Energy’s “Carbon Negative Shot” program, which “hopes to bring costs below $100 per ton within a decade.” - Target 10.3: Ensure equal opportunity and reduce inequalities of outcome…

The discussion about the “duty to compensate the net losers” of SRM and the potential for a “non-compensable ‘moral remainder'” directly relates to reducing inequalities of outcome from global policies.

3. Are there any indicators mentioned or implied in the article that can be used to measure progress towards the identified targets?

Identified Indicators

The article provides several quantitative and qualitative indicators that can be used to measure the scale of the problems discussed and the potential progress towards the identified targets.

- Total greenhouse gas emissions per year (Indicator for Target 13.2): The article states that in 2024, “humans released 37.8 billion tons of carbon dioxide… the highest ever annual level.” This is a direct measure of the failure of current climate mitigation efforts.

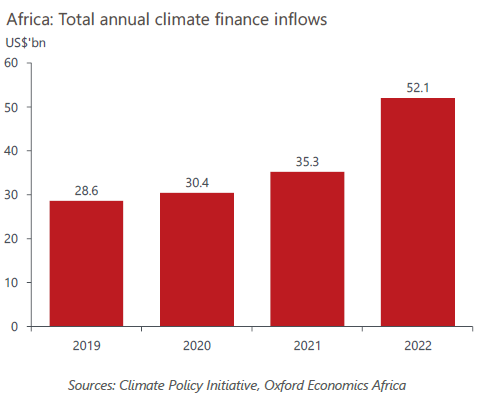

- Economic loss due to climate-related disasters (Indicator for Targets 13.1 & 8.1): The article provides several estimates of economic impact, which serve as indicators of climate risk. These include:

- A projection that “unmitigated climate change will lead to a 10% loss in global GDP.”

- An estimate that SRM side-effect harms “would fall between $0 and $809 billion annually.”

- Amounts provided and mobilized for climate finance (Indicator for Target 13.a): The article provides a specific figure for the “loss and damage” fund, stating that “less than $750 million had been pledged,” which can be used as an indicator to track financial commitments from developed to developing nations.

- Proportion of population affected by policy outcomes (Indicator for Target 10.3): The estimate that “between 0% and 7% of humanity can expect to be harmed by SAI” serves as a powerful indicator of the unequal outcomes of a global climate intervention policy.

- Cost of sustainable technologies (Indicator for Target 9.5): The article mentions the “industry target of $100 per captured ton of CO2” for Direct Air Capture (DAC) technology. This cost is a key indicator of the technological and economic feasibility of large-scale carbon removal.

- Public expenditure on sustainable development (Indicator for Target 17.17): The estimated cost of an LCDR program at “$950 billion a year in public spending” is an indicator of the scale of investment required for such a partnership.

- International agreements and governance frameworks (Indicator for Target 16.6): The article qualitatively indicates a lack of progress by citing the “unsuccessful and ‘surprisingly bitter’ negotiations at the UN Environment Assembly (UNEA)” and the call by some nations for a “global SRM non-use agreement.”

4. Create a table with three columns titled ‘SDGs, Targets and Indicators” to present the findings from analyzing the article.

| SDGs | Targets | Indicators Identified in the Article |

|---|---|---|

| SDG 13: Climate Action |

13.1: Strengthen resilience and adaptive capacity to climate-related hazards.

13.2: Integrate climate change measures into national policies, strategies and planning. 13.a: Implement the commitment… to a goal of mobilizing jointly $100 billion annually… for developing countries. |

– Economic damages from unmitigated climate change projected to “reach into the trillions annually.” – SRM side-effects creating “novel risks of floods or droughts.” – Total annual CO2 emissions: “37.8 billion tons of carbon dioxide in 2024.” – Amount pledged to the “loss and damage” fund: “less than $750 million.” |

| SDG 16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions |

16.6: Develop effective, accountable and transparent institutions at all levels.

16.8: Broaden and strengthen the participation of developing countries in the institutions of global governance. |

– Failure of international negotiations on SRM governance at the UN Environment Assembly (UNEA). – Call for a “global SRM non-use agreement” by the European Parliament and African nations. – Uneven impacts of SRM, with effects “most pronounced in South America and Sub-Sahel Africa.” |

| SDG 17: Partnerships for the Goals | 17.16: Enhance the global partnership for sustainable development… |

– Proposal for an LCDR program “administered by a consortium of developed states.” – Failure of “multilateral emissions treaties” to curb emissions. |

| SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities | 10.3: Ensure equal opportunity and reduce inequalities of outcome… |

– Proportion of global population harmed by SAI: “between 0% and 7% of humanity.” – Estimated annual cost of compensation for side-effect harms: “$0 and $809 billion.” |

| SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth | 8.1: Sustain per capita economic growth… | – Projected economic impact of unmitigated climate change: “a 10% loss in global GDP.” |

| SDG 9: Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure | 9.5: Enhance scientific research, upgrade the technological capabilities… |

– Cost target for Direct Air Capture (DAC) technology: “$100 per captured ton of CO2.” – Existence of research initiatives like the “Carbon Negative Shot.” |

| SDG 2 & 15: Zero Hunger & Life on Land |

2.4: Ensure sustainable food production systems…

15.5: …halt the loss of biodiversity. |

– Qualitative risk that large-scale CDR may lead to “food insecurity.”

– Qualitative risk that large-scale CDR may lead to “biodiversity loss.” |

Source: nature.com

What is Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0

.jpg?#)