The Hauraki Gulf Marine Protection Act: Turning the Tide for the Marine Park – greenpeace.org

Report on the Hauraki Gulf/Tīkapa Moana Marine Protection Act and its Alignment with Sustainable Development Goals

Executive Summary

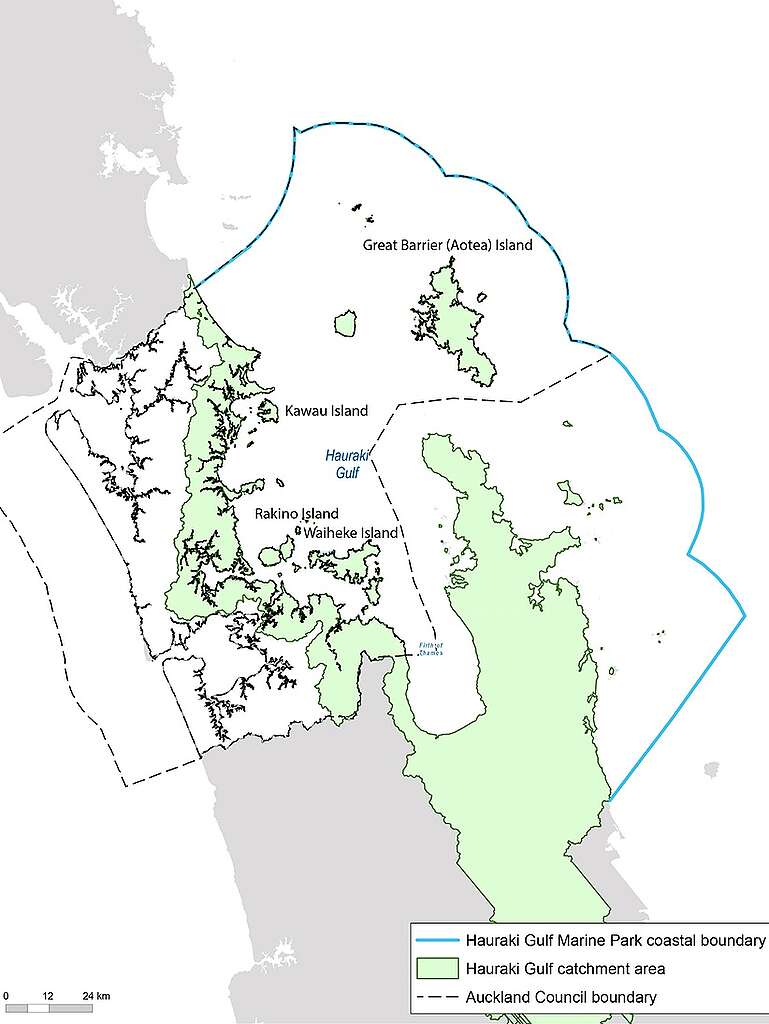

The recent enactment of the Hauraki Gulf/Tīkapa Moana Marine Protection Act represents a significant development in marine conservation for Aotearoa New Zealand. The Act aims to restore the ecological vitality of the Hauraki Gulf Marine Park, a national taonga of significant cultural and biological importance. While the legislation introduces positive measures that align with Sustainable Development Goal 14 (Life Below Water), it also contains considerable shortcomings that undermine its effectiveness and fall short of international conservation targets. This report analyses the Act’s provisions, its alignment with the SDGs, and the broader context of marine protection efforts in the region.

Background and Context of the Act

The Hauraki Gulf Marine Park, established over two decades ago, is an area of immense ecological and cultural value. Despite its protected status, the marine environment has continued to decline due to factors including over-exploitation, pollution, and climate change. The new Act is the result of extensive advocacy from iwi, community groups, and environmental organisations, aiming to reverse this degradation.

Key Provisions of the Act

- Establishes 19 new marine protected areas (MPAs).

- Creates High Protection Areas (HPAs) where most fishing is prohibited to facilitate habitat recovery.

- Designates Seafloor Protection Areas, banning destructive fishing methods like bottom trawling and dredging in specific zones.

- Extends two existing marine reserves.

Positive Outcomes and Contributions to Sustainable Development Goals

Increased Marine Protection (SDG 14.2, SDG 14.5)

The most significant achievement of the Act is the expansion of highly protected areas within the Gulf from 0.3% to nearly 6%. This measure is a direct contribution to achieving SDG Target 14.5, which calls for the conservation of at least 10% of coastal and marine areas. By restricting exploitation in these zones, the Act supports SDG Target 14.2, which focuses on sustainably managing and protecting marine and coastal ecosystems to avoid significant adverse impacts.

Ecological Recovery Potential

The increased protection provides a critical opportunity for the recovery of severely depleted species and habitats. Reports indicate catastrophic declines in the Gulf’s biodiversity, including:

- A 97% decline in whales and dolphins.

- A 57% decline in key fish stocks.

- Functional extinction of crayfish and scallops in some areas.

The new protections offer a lifeline for these species and are essential for restoring the overall health and mauri (life force) of the marine park, directly supporting the objectives of SDG 14.

Deficiencies and Misalignment with Sustainable Development Goals

Despite its positive aspects, the Act contains several critical flaws that limit its conservation impact and create dangerous precedents for marine protection.

Continuation of Destructive Practices (SDG 14.2, SDG 13)

A major failing of the Act is that it does not implement a comprehensive ban on bottom trawling, a practice identified as a primary driver of ecological degradation in the Gulf. Allowing this activity to continue, even outside of newly protected zones, undermines efforts to protect sensitive seafloor ecosystems, as stipulated in SDG 14.2. Furthermore, by disturbing carbon-rich sediment, bottom trawling counteracts climate mitigation efforts, conflicting with the principles of SDG 13 (Climate Action).

Compromised High Protection Areas (SDG 16)

A last-minute amendment permits commercial ring-net fishing to continue within two of the newly established High Protection Areas. This provision has drawn widespread criticism as it fundamentally compromises the integrity of these zones, effectively turning them into fisheries management areas rather than sanctuaries for recovery. This action raises concerns regarding governance and due process, potentially conflicting with SDG 16 (Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions) by prioritising commercial interests over publicly supported conservation objectives and transparent decision-making.

Failure to Meet International Commitments (SDG 14.5)

While an improvement, the expansion of protection to 6% of the Gulf remains significantly below the target set by the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, to which New Zealand is a signatory. This framework commits nations to protecting 30% of marine areas by 2030. The Act’s limited scope indicates a lack of ambition in meeting this critical international target, essential for fulfilling SDG 14.5 and addressing the global biodiversity crisis.

Inadequate Recognition of Indigenous Partnership (SDG 16, SDG 17)

The legislation has been criticised for inadequately recognising the role of mana whenua as key partners in the Gulf’s management. Amendments to ensure mandatory consultation with iwi, hapū, and whānau were not adopted, weakening the collaborative governance framework. This exclusion runs contrary to the principles of inclusive institutions (SDG 16) and effective partnerships (SDG 17), which are vital for sustainable and equitable resource management.

The Role of Collective and Regional Action

Community-Driven Initiatives (SDG 17)

The Act itself is a testament to the power of collective action, stemming from years of work by a coalition of local stakeholders. This collaborative approach exemplifies SDG 17 (Partnerships for the Goals). However, the final legislation demonstrates that central government actions can override community consensus in favour of industry interests.

Regional Governance as a Corrective Mechanism

In response to perceived inaction at the national level, regional bodies are taking the lead. The Waikato Regional Council’s proposal to ban bottom trawling along the Coromandel coast illustrates how local governance can drive meaningful marine protection when central government fails to act. This multi-level governance approach is crucial for achieving comprehensive environmental outcomes.

Conclusion

The Hauraki Gulf/Tīkapa Moana Marine Protection Act is a paradoxical piece of legislation. It marks a step forward for marine conservation in New Zealand but is simultaneously undermined by significant concessions to commercial interests and a lack of alignment with global biodiversity targets and indigenous partnership principles.

Recommendations for Future Action

- Implement a complete ban on bottom trawling and other destructive fishing methods throughout the entire Hauraki Gulf Marine Park to fully align with SDG 14.2.

- Revise the Act to remove exemptions for commercial fishing within High Protection Areas, ensuring their integrity as genuine sanctuaries.

- Develop a clear and ambitious roadmap to achieve the 30% marine protection target by 2030, in line with international commitments and SDG 14.5.

- Strengthen co-governance frameworks to ensure the meaningful and mandatory inclusion of mana whenua in all decision-making processes, upholding the principles of SDG 16 and SDG 17.

Continued pressure from community, regional, and national stakeholders is essential to ensure that the protection of Tīkapa Moana is strengthened to a level that can genuinely restore its ecological health and fulfill New Zealand’s commitments to the Sustainable Development Goals.

Analysis of the Hauraki Gulf Protection Bill Article

1. Which SDGs are addressed or connected to the issues highlighted in the article?

The article on the Hauraki Gulf Protection Bill addresses several Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) due to its focus on marine conservation, biodiversity, governance, and community participation. The primary SDGs connected are:

- SDG 14: Life Below Water: This is the most central SDG, as the entire article revolves around the conservation and sustainable use of the Hauraki Gulf, a significant marine ecosystem. It discusses marine protected areas, the impact of fishing, and the health of marine species.

- SDG 15: Life on Land: While focused on the ocean, this goal is relevant through its aim to halt biodiversity loss (Target 15.5). The article details the catastrophic decline of marine wildlife, including seabirds, which connect marine and terrestrial ecosystems, and the protection of coastal habitats.

- SDG 16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions: The article touches upon issues of governance, institutional integrity, and inclusive decision-making. It critiques the legislative process, mentions “regulatory capture,” and highlights the lack of consultation with indigenous communities (*mana whenua*), connecting directly to the need for accountable and inclusive institutions.

- SDG 17: Partnerships for the Goals: The article emphasizes the importance of collaboration. It credits the creation of the protection plan to the “decades-long advocacy by local iwi, community, environmental groups and recreational fishers,” showcasing a multi-stakeholder partnership essential for achieving sustainable development.

2. What specific targets under those SDGs can be identified based on the article’s content?

Based on the article’s discussion, several specific SDG targets can be identified:

-

Target 14.2: By 2025, protect and restore marine and coastal ecosystems.

- Explanation: The article’s core subject is the Hauraki Gulf Protection Act, which aims to restore the “mauri (life force), habitats, and living species of Tīkapa Moana.” It discusses the creation of new marine protected areas specifically “to allow habitats to recover” from degradation caused by over-exploitation, sediment runoff, and pollution.

-

Target 14.4: By 2025, end overfishing and destructive fishing practices.

- Explanation: The article heavily criticizes that “bottom trawling, the most destructive kind of fishing, will still be allowed to continue in the marine park.” It also points out that “more than half of all key fish stocks (57%) have disappeared,” which is a direct consequence of over-exploitation and unsustainable fishing practices that this target aims to eliminate.

-

Target 14.5: By 2025, conserve at least 30% of marine and coastal areas.

- Explanation: The article explicitly references this global target, stating, “New Zealand is a signatory to the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, which requires 30% of marine and coastal areas to be protected by 2030.” It then critiques the new law because the “increased protected area to 6% of the Gulf remains far below the internationally recognized target.”

-

Target 15.5: Halt the loss of biodiversity and prevent the extinction of threatened species.

- Explanation: The article provides a strong justification for this target by listing alarming statistics on biodiversity loss in the Gulf, such as a “catastrophic 97% decline” in whales and dolphins and the fact that “crayfish and scallops are functionally extinct in some areas.” The act is described as a “lifeline for species whose numbers have greatly suffered.”

-

Target 16.7: Ensure responsive, inclusive, participatory and representative decision-making at all levels.

- Explanation: The article criticizes the legislative process for its lack of inclusivity, noting the “criticism regarding the recognition of mana whenua” and that “amendments designed to ensure mandatory consultation with mana whenua/iwi were not adopted.” This highlights a failure to achieve the participatory decision-making this target calls for.

-

Target 17.17: Encourage and promote effective public, public-private and civil society partnerships.

- Explanation: The article praises the “power of collective, sustained action” and notes that the protection plan is the “result of decades-long advocacy by local iwi, community, environmental groups and recreational fishers.” This collaboration, which led to the “SeaChange – Tai Timu Tai Pari” plan, is a clear example of the multi-stakeholder partnerships this target promotes.

3. Are there any indicators mentioned or implied in the article that can be used to measure progress towards the identified targets?

Yes, the article mentions several quantitative and qualitative indicators that can be used to measure progress:

- Indicator for Target 14.5 (Coverage of protected areas): The article provides precise figures that serve as a direct indicator. It states that highly protected areas have increased from “just 0.3% of the Park” to “nearly 6%.” Progress can be measured against the international target of “30% marine protection” also mentioned in the text.

-

Indicators for Target 14.2 & 15.5 (Ecosystem health and biodiversity): The article provides baseline data on species decline that can be used as indicators to measure recovery. These include:

- The “97% decline” in whales and dolphins.

- The disappearance of “57% of all key fish stocks.”

- The loss of “more two-thirds of seabirds.”

- The status of crayfish and scallops as “functionally extinct in some areas.”

Monitoring these populations over time would indicate whether the protection measures are effective.

- Indicator for Target 14.4 (Destructive fishing practices): The extent of bottom trawling can be used as an indicator. The article implies this by stating the law “excludes bottom trawling only from selected areas of the Gulf.” An indicator of progress would be the total area of the marine park where bottom trawling is banned. Public opinion surveys, such as the one cited showing “84% of residents around the Gulf want a ban on bottom trawling,” can also serve as an indicator of social demand for policy change.

- Indicator for Target 16.7 (Inclusive decision-making): A qualitative indicator is the level of participation and influence of indigenous groups (*mana whenua*) in governance. The article implies a negative indicator by stating that “amendments designed to ensure mandatory consultation with mana whenua/iwi were not adopted,” suggesting that the decision-making process was not fully inclusive.

4. SDGs, Targets, and Indicators Table

| SDGs | Targets | Indicators Identified in the Article |

|---|---|---|

| SDG 14: Life Below Water |

14.2: Protect and restore marine and coastal ecosystems.

14.4: End overfishing and destructive fishing practices. 14.5: Conserve at least 30% of marine and coastal areas. |

– Statistics on species decline (e.g., “97% decline” in whales and dolphins, “57%” of fish stocks gone) as a baseline for recovery.

– Area of the marine park where destructive practices like bottom trawling are permitted versus banned. – Percentage of the marine park designated as a protected area (Increased from 0.3% to 6%, against a 30% target). |

| SDG 15: Life on Land | 15.5: Halt the loss of biodiversity and prevent the extinction of threatened species. | – Population trends of threatened or declining species mentioned (Bryde’s Whales, dolphins, seabirds, crayfish, scallops). – Status of species being “functionally extinct” in certain areas. |

| SDG 16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions | 16.7: Ensure responsive, inclusive, participatory and representative decision-making. | – Adoption or rejection of amendments for mandatory consultation with indigenous groups (*mana whenua*). – Level of influence of industry lobbying versus community and expert advice in final legislation. |

| SDG 17: Partnerships for the Goals | 17.17: Encourage and promote effective public, public-private and civil society partnerships. | – The existence and influence of multi-stakeholder collaborations (e.g., the “SeaChange – Tai Timu Tai Pari” plan created by iwi, community, and environmental groups). |

Source: greenpeace.org

What is Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0