How Indigenous Techniques Saved a Community From Wildfire

A raging Canadian wildfire reached a fire prevention zone on the fringes of the city of Kelowna and sputtered to a halt, burning just a single house thanks to the use of fire prevention and mitigation methods based on Indigenous techniques. Indigenous communities have been disproportionately impacted by wildfires and have thus developed effective fire mitigation methods. The thinning of forests, trimming of lower branches, and removal of smaller younger trees that are more likely to burn all help stop or slow the spread of fire, and allow older more fire resistant trees to survive. Now Canadian logging companies and Canada as a whole are looking to these practices to better prepare for fires and protect forests and nearby communities.

A movement to fight wildfires by making forests more resilient and, in some cases, deliberately setting blazes is gaining ground in Canada.

Credit: Amber Bracken for The New York Times

Reporting from Kelowna, Nelson and Vernon, British Columbia

The wildfire was blazing a clear path toward a Canadian lakeside tourist spot in British Columbia with a population of 222,000 people.

The fire advanced on the city of Kelowna for 19 days — consuming 976 hectares, or about 2,400 acres — of forest. But at the suburban fringes, it encountered a fire prevention zone and sputtered, burning just a single house.

The fire prevention zone — an area carefully cleared to remove fuel and minimize the spread of flames — was created by a logging company owned by a local Indigenous community. And as a new wildfire has stalked the suburb of West Kelowna this month, its history with the previous one — the Mount Law fire, in 2021 — offers a valuable lesson: A well-placed and well-constructed fire prevention zone can, under the right conditions, save homes and lives.

It’s a lesson not only for Kelowna but also for a growing number of places in Canada and elsewhere threatened by increased wildfire amid climate change.

“When you think about how wildfire seasons are playing out, if we invested more into the proactive, then we would need less of that reactive wildfire response,” said Kira Hoffman, a wildfire researcher at the University of British Columbia. “We’re not going to see probably the effects of a lot of this mitigation and treatment for 10 or 20 years. But that’s when we’re really going to need it.”

Wildfires are an essential component of the natural cycle of forests, but in recent years, more of them have grown so big that containment is nearly impossible. Fire prevention zones — created in the off season — can help slow approaching blazes so that people can escape, and can also enable firefighters to gain control over some areas.

The creation of these zones is being greeted with renewed interest in parts of Canada, including in the western provinces of British Columbia and Alberta. Interest has especially peaked in Indigenous communities, which have been most affected by the country’s wildfires.

Ten times as many acres have burned in Canada this year than all of last fire season, at times sending smoke as far south as Georgia and as far east as Europe. The current fire in West Kelowna has breached areas that lack fire prevention zones, consuming 110 buildings and upending the lives of about 30,000 evacuees in the area.

Image: Sap from a scorched tree shows it survived a wildfire in West Kelowna, British Columbia. Credit: Amber Bracken for The New York Times

By contrast, the 50-acre fire resistant zone starved the in 2021 fire, allowing firefighters to suppress it, keeping it away from houses.

The logging company, Ntityix Development, that created that fire prevention zone drew in part on traditional Indigenous forestry practices, including thinning the forest; cleaning up debris on the floor; and burning the debris and ground cover in a controlled way to prevent it from becoming fuel for wildfires — an act once banned by the provincial government.

“This was the first test of any of the work that we’ve done and it indicates to me that it works,” said Dave Gill, the general manager of forestry at Ntityix Development, which is owned by the Westbank First Nation, as he walked through the still largely intact forest a few weeks before this year’s fire began. “It certainly stopped it advancing.”

Image: Dave Gill, the general manager of Ntityix Development, in an area of forest largely spared with the help of mitigation efforts. Credit: Amber Bracken for The New York Times

Ntityix’s strategy helps slow fires by reducing the flammability of forests showered by airborne embers, the main way wildfires spread, said Dr. Hoffman, a former wildfire fighter.

In 2015, six years before the Mount Law fire threatened Kelowna, Mr. Gill began creating the fire prevention zone, called the Glenrosa project, named after a forested neighborhood in West Kelowna. A key objective was keeping any fires on the forest floor.

“If you have a fire and it’s on a surface, it’s fairly easy to contain or to fight,” Mr. Gill said. “But as soon as it gets up into the crowns, it’s game over.”

The project also conserved mature trees with thick fire resistant bark and only harvested less valuable but more combustible young trees — a reversal of customary forestry practice.

Image: An area of managed forest in Nelson, British Columbia. During a forest fire, the low-lying vegetation and the organic content of the soil burn away, typically leaving mature trees scorched but alive. Credit: Amber Bracken for The New York Times

Before coming to Ntityix, Mr. Gill, who is not Indigenous, had a decades long career in government, as well as with commercial forestry and consulting companies.

He said the First Nation's elders, who have instructed him to manage the forest on a 120-year timeline, and his Indigenous co-workers changed how he thinks about the forest. “We’re leaving the trees that have the most timber value behind,” Mr. Gill, said. “This is trying to just instill a different paradigm in the way that you look at the forest, not just putting dollar signs on trees.”

After thinning the forest, Ntityix crews finished the project in 2016 by pruning the lowest 10 or 12 feet of limbs on the remaining trees so that they won’t become a ladder for fire to climb. The accumulated debris from the forest floor was either chipped and trucked away or burned.

In the areas where it is logging, Ntityix does not clear cut, the standard industry practice, but does some selective logging and leaves stands of fire resistant deciduous trees intact.

Image: The section wasn’t mitigated for wildfire and so most of the trees were killed in the 2021 fire. Credit: Amber Bracken for The New York Times

While billions of dollars have been spent putting out Canadian wildfires — British Columbia alone spent nearly 1 billion Canadian dollars in 2021 — funding for measures to make forests less welcoming to flames has generally been modest. Nor has the value of such measures been fully embraced by everyone in Canada’s forestry establishment.

Although more mitigation efforts are needed, their general effectiveness is being undermined by the growing intensity and size of wildfires, said Mike Flannigan, a wildfire scientist at Thompson Rivers University in Kamloops, British Columbias.

“When things get extreme, the fire will do what the fire will do,” he said. “Unless you treat 40 percent of the landscape, it’s not going to work because the fire will just go around it or jump over.”

Dr. Hoffman, however, is less pessimistic, and says that not enough large-scale risk reduction has been attempted to judge its effectiveness.

“There are not a lot of economic incentives for doing” what Ntityix did, Dr. Hoffman said. “It’s not really sexy to go and take out six-inch pine from the forest.”

The measures taken by Ntityix and other companies, many of them owned by First Nations communities or their members, are labor intensive and costly. The company has committed 100,000 Canadian dollars a year to carrying out a variation of its work that turns logging roads into wildfire mitigation zones, a process that will likely take decades.

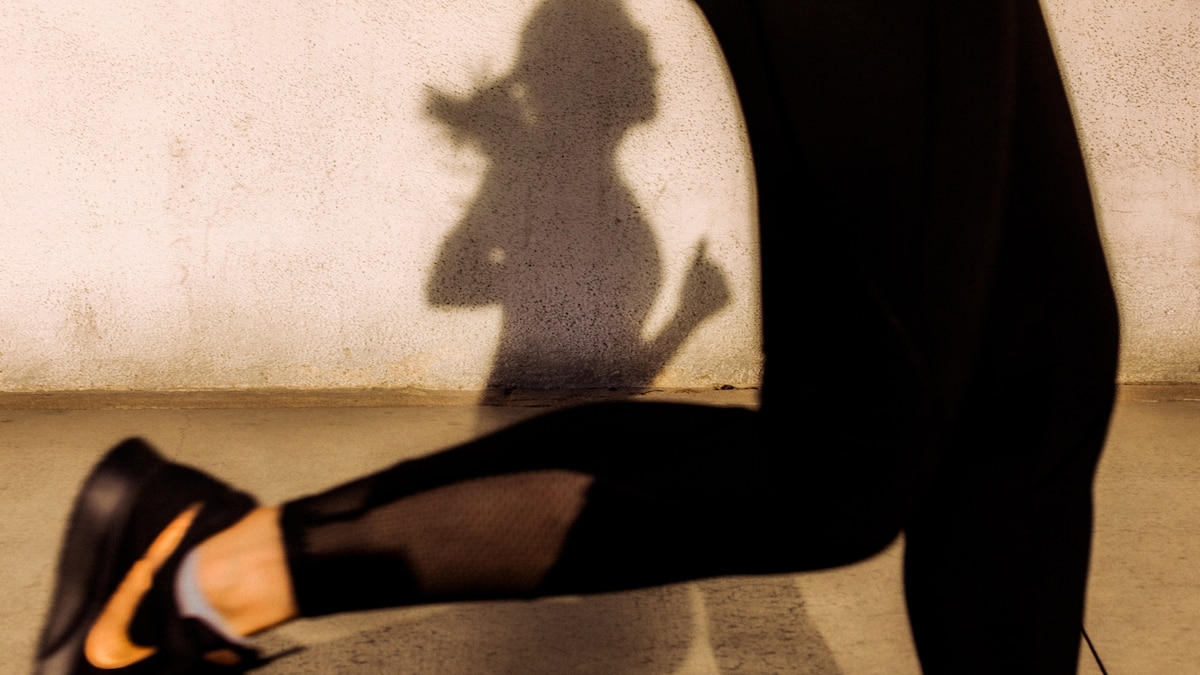

Craig Moore — a member of the Syilx Okanagan Nation, in British Columbia — is also a former municipal firefighter and owns a company that does fire mitigation in forests.

Image: Craig Moore showing an area in British Columbia where fuel management — spacing trees and removing brush and lower branches of trees — has been effective in helping control wildfires. Credit: Amber Bracken for The New York Times

During an interview at his company, Rider Ventures, in Vernon, British Columbia, he recalled how his efforts slowed a fire in the province in 2021. Mr. Moore said that afterward, the area’s wildfire ranking fell from 6 — the most severe on the province’s scale — to 2, giving firefighters the chance to save 500 homes.

“Having water and trees are our biggest things,” Mr. Moore said, standing amid a forest where his company had worked. “If we lose that, we’re all going to perish pretty fast.”

A native of Windsor, Ontario, Ian Austen was educated in Toronto and currently lives in Ottawa. He has reported for The Times about Canada for more than a decade. More about Ian Austen

What is Your Reaction?

Like

1

Like

1

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0