Affordable housing movement in CDMX gains ground with third anti-gentrification march – Mexico News Daily

Report on Anti-Gentrification Protest in Mexico City and its Alignment with Sustainable Development Goals

Introduction: Civic Action Against Urban Displacement

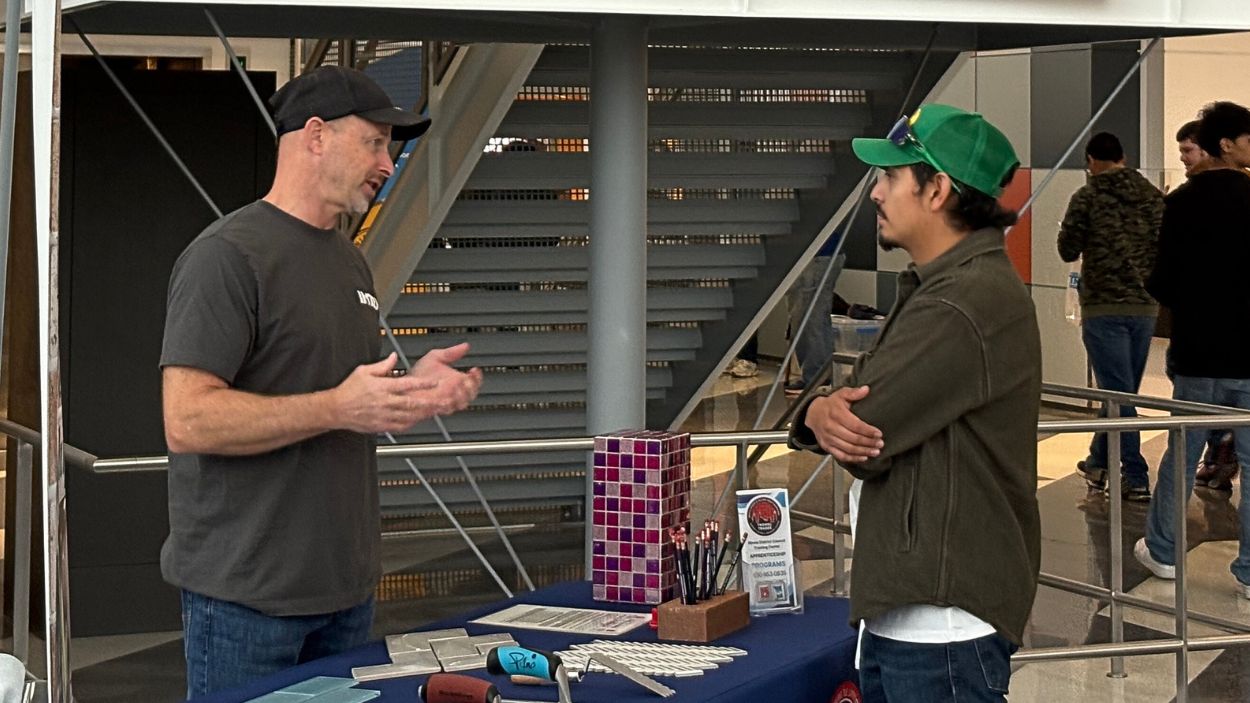

On Saturday, approximately 200 individuals participated in the “Third March Against Gentrification” in Mexico City, marking the third such demonstration in July. The protest highlights escalating public concern over urban development patterns that conflict with the principles of SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities. Unlike previous related events, city authorities reported that the march concluded without significant incidents, allowing protesters to exercise their rights under SDG 16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions.

Protest Details and Route

The demonstration commenced at the Benito Juárez Hemicycle in Alameda Central Park and proceeded through the city’s historic center. Participants, including a significant number of university students, marched to the Zócalo before concluding at the Juárez metro station. A planned route to the United States Embassy was altered at the last minute. The U.S. Embassy had previously issued a security alert, citing incidents of vandalism during the July 4 and July 20 protests.

Core Grievances and SDG Implications

The protest centered on the social and economic displacement of local residents, a direct challenge to the achievement of several Sustainable Development Goals.

Key Demands and Their Relation to SDG 11

Protesters’ slogans articulated a clear demand for urban policies aligned with SDG 11, which aims to make cities inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable. Core messages included:

- “Decent housing for Mexicans”: This directly echoes Target 11.1 of the SDGs, which calls for access for all to adequate, safe, and affordable housing.

- “Get out Airbnb”: This points to the proliferation of short-term tourist rentals, which participants claim displaces long-term residents and undermines community stability, further contravening Target 11.1.

- “The [historic] center is not for sale” and “Our neighborhood is not a warehouse”: These slogans protest the commercialization of residential and cultural spaces, including the conversion of buildings into warehouses for goods sold at Chinese-operated plazas. This trend erodes the cultural heritage and social fabric essential for sustainable communities (Target 11.4).

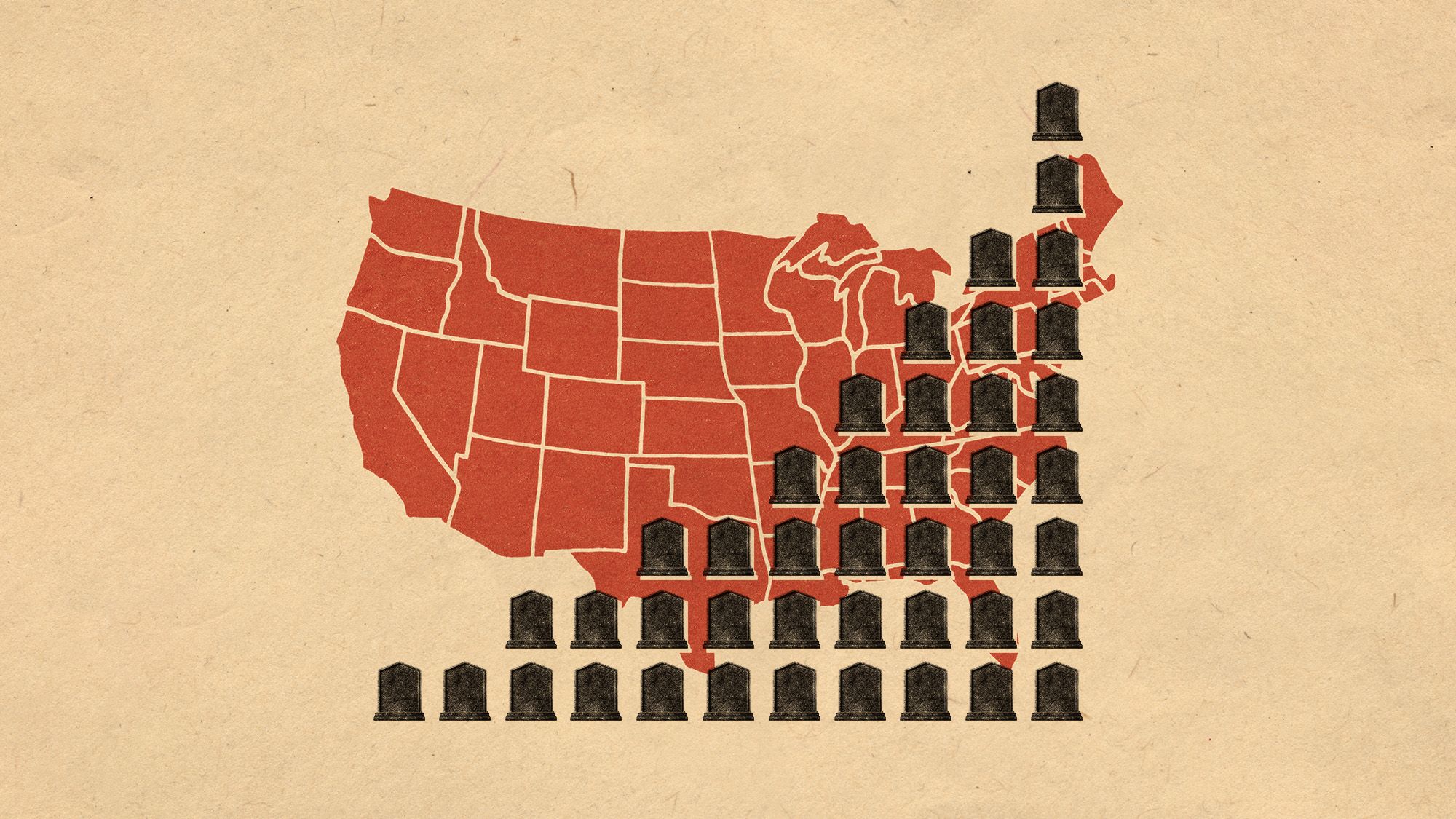

Socio-Economic Impacts and SDG 10

The phenomenon of gentrification, which protesters labeled a form of colonization (“To gentrify is to colonize”), is a critical issue under SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities. The displacement of families and the increase in the cost of housing exacerbate economic disparities and threaten the social inclusion of lower-income residents. Protesters argue that current development models prioritize foreign investment and tourism over the well-being of local citizens, deepening inequality rather than reducing it.

Government and Institutional Response

Official Statements and Security Measures

The Mexico City government officially described the march as peaceful, noting that its presence was intended to ensure an orderly protest. However, authorities also reported the following actions:

- Confiscation of items deemed potential weapons, including bats, chains, a hammer, and a Molotov cocktail.

- The occurrence of minor scuffles during the confiscation.

- Vandalism involving graffiti inside the Juárez metro station by a group of protesters.

These events highlight the delicate balance required under SDG 16 to protect the right to peaceful assembly while maintaining public order.

Policy Context and Ongoing Challenges

The recent protests occur despite government initiatives aimed at mitigating the housing crisis. These include:

- A plan announced by Mayor Clara Brugada to create thousands of affordable housing units, a direct policy response to the goals of SDG 11.

- A reform approved by Mexico City’s Congress to limit online vacation rentals to 180 days per year.

Despite these measures, protesters accuse the government of supporting gentrification. President Claudia Sheinbaum has acknowledged the need to address the issue while also denouncing xenophobia. The continued demonstrations suggest that current policies are perceived as insufficient to protect communities from displacement.

Conclusion: A Call for Sustainable and Inclusive Urban Development

The series of anti-gentrification marches in Mexico City underscores a growing demand for a development model that aligns with the principles of the Sustainable Development Goals. The protesters’ assertion that “Gentrification is not development. It’s dispossession disguised as progress” serves as a powerful critique of urban growth that fails to be inclusive. The Youth Front for Housing has announced the “Regional Conference against Gentrification and Dispossession” for August 9, indicating a sustained effort to advocate for policies that ensure living in dignity is a right for all citizens, not a privilege, in direct accordance with the vision of SDG 1 (No Poverty), SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities), and SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities).

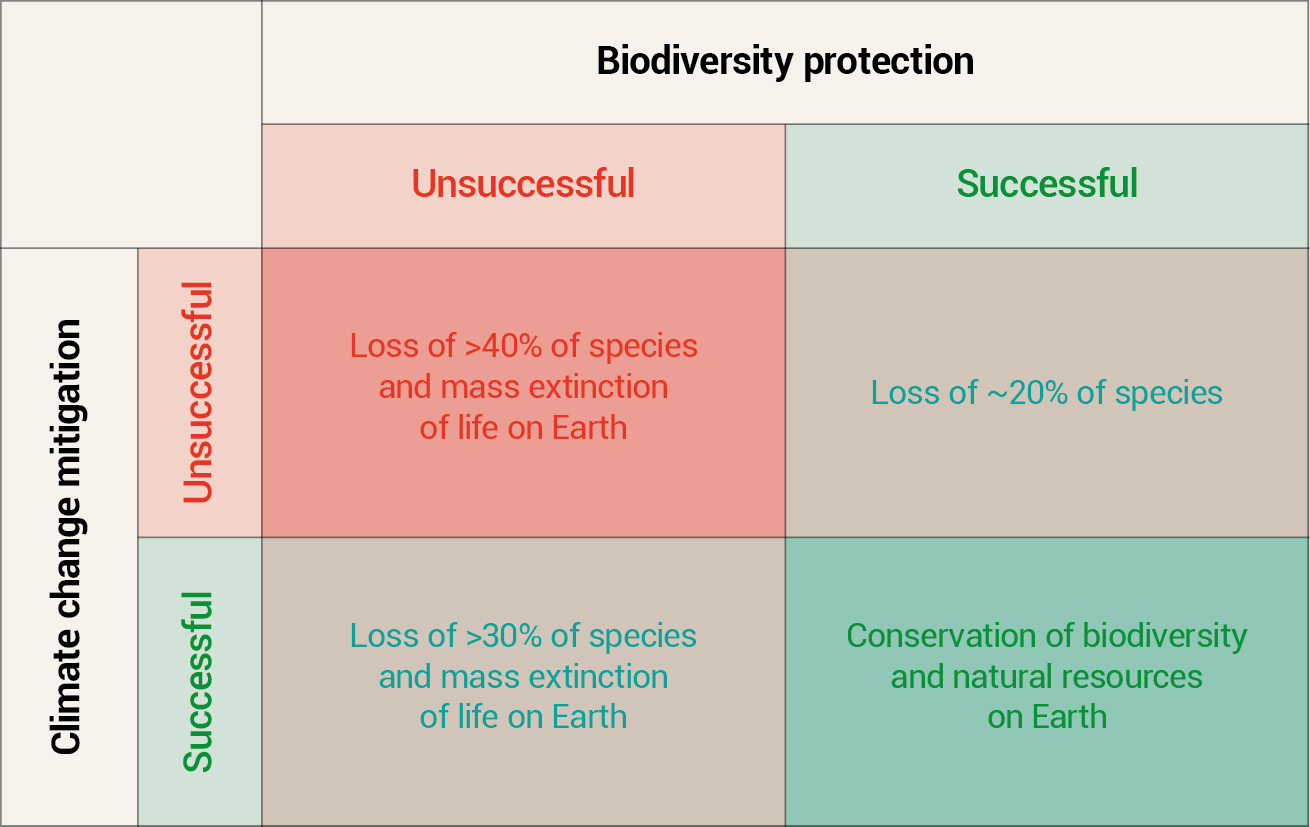

1. Which SDGs are addressed or connected to the issues highlighted in the article?

The article on anti-gentrification protests in Mexico City touches upon several Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) due to the multifaceted nature of gentrification, which involves housing, social equity, and urban development.

-

SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities

The core of the protest is the “social displacement” of local residents due to rising costs driven by an influx of wealthier individuals, including foreigners. This creates and exacerbates inequalities within the city. Protesters’ slogans like “To gentrify is to colonize” and their fight against a “change that excludes and erases us” directly point to the growing gap between different economic and social groups within the urban community.

-

SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities

This is the most central SDG to the article. The issues of housing affordability, urban planning, and cultural heritage are at the forefront of the protests. The demand for “Decent housing for Mexicans,” the opposition to buildings being converted into Airbnbs or warehouses, and the fight to protect the character of neighborhoods like the “historic center” all fall under the goal of making cities inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable for all inhabitants, not just a privileged few.

-

SDG 16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions

The article details the interactions between citizens and the state. The protests themselves are a form of civic participation, demanding responsive governance. The government’s response, including police presence, the seizure of potential weapons, and policy announcements (like creating affordable housing and limiting Airbnb rentals), reflects the role of institutions in managing social conflict and addressing public grievances. The protesters’ accusation that the “government of supporting the process of gentrification” questions the justice and effectiveness of these institutions.

2. What specific targets under those SDGs can be identified based on the article’s content?

Based on the specific issues raised by the protesters and the government actions mentioned, several SDG targets can be identified:

-

Target 11.1: By 2030, ensure access for all to adequate, safe and affordable housing and basic services.

This target is directly addressed. The protests are a response to the “increase in the cost of housing” and the lack of affordable options. Protesters hold signs demanding “Decent housing for Mexicans” and oppose the conversion of long-term apartments into short-term rentals, which displaces families. The government’s plan to “create thousands of affordable housing units” is a direct policy action aimed at this target.

-

Target 11.3: By 2030, enhance inclusive and sustainable urbanization and capacity for participatory, integrated and sustainable human settlement planning and management.

The protesters feel excluded from the changes happening in their city, stating they are opposed to “change that excludes and erases us.” Their marches and the planned “Regional Conference against Gentrification” are demands for a more participatory and inclusive approach to urban development, where the needs of existing communities are prioritized. The phenomenon of “social displacement” is a clear failure of inclusive human settlement management.

-

Target 11.4: Strengthen efforts to protect and safeguard the world’s cultural and natural heritage.

The protests take place in and concern the “historic center of Mexico City.” A placard reading “The [historic] center is not for sale” explicitly shows a desire to protect the cultural and social heritage of this area from purely commercial development that displaces its community and character.

-

Target 10.2: By 2030, empower and promote the social, economic and political inclusion of all, irrespective of… origin or economic or other status.

The article describes a conflict where long-term residents (of a lower economic status) are being displaced by wealthier newcomers (“foreigners, especially U.S. citizens”). The protesters’ fight to “defend our neighborhoods, our histories and our way of living” is a struggle against social and economic exclusion driven by gentrification.

3. Are there any indicators mentioned or implied in the article that can be used to measure progress towards the identified targets?

The article mentions or implies several qualitative and quantitative indicators that could be used to track progress.

-

Indicators for Target 11.1 (Affordable Housing)

- Policy and Regulation: The article explicitly mentions a policy indicator: the “reform that established a 180-day-per-year limit on online vacation rentals.” The existence and enforcement of such regulations can be measured.

- Housing Supply: A quantitative indicator is mentioned in the government’s response: the plan to “create thousands of affordable housing units.” The number of units actually built would be a direct measure of progress.

- Housing Affordability: The “increase in the cost of housing” is the problem statement. Tracking rental and property prices in neighborhoods like Roma, Condesa, and the historic center would be a key indicator. The prevalence of short-term rentals (e.g., the number of Airbnb listings) is another implied indicator of housing stock being removed from the long-term market.

-

Indicators for Target 11.3 (Inclusive Urbanization)

- Civic Participation: The frequency and scale of protests (“Third March Against Gentrification,” with “around 200 people”) serve as an indicator of public dissatisfaction and the perceived lack of participatory planning. The planned “Regional Conference against Gentrification” is another indicator of organized citizen engagement.

- Social Displacement: While not quantified, “social displacement” is repeatedly cited as a key problem. Tracking the rate of resident turnover and the demographic/economic changes in affected neighborhoods would be a direct, albeit complex, indicator.

4. Table of SDGs, Targets, and Indicators

| SDGs | Targets | Indicators Identified in the Article |

|---|---|---|

| SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities | 11.1: Ensure access for all to adequate, safe and affordable housing. |

|

| SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities | 11.3: Enhance inclusive and sustainable urbanization and participatory planning. |

|

| SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities | 11.4: Protect and safeguard the world’s cultural heritage. |

|

| SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities | 10.2: Empower and promote the social, economic and political inclusion of all. |

|

| SDG 16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions | 16.7: Ensure responsive, inclusive, participatory and representative decision-making. |

|

Source: mexiconewsdaily.com

![]()

What is Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0

.jpg?#)