An invisible threat to newborns’ brains may be hiding in the air we breathe – psypost.org

Report on Prenatal Air Pollution Exposure and Neonatal Brain Development in the Context of Sustainable Development Goals

Introduction: Aligning Urban Health with SDG 3 and SDG 11

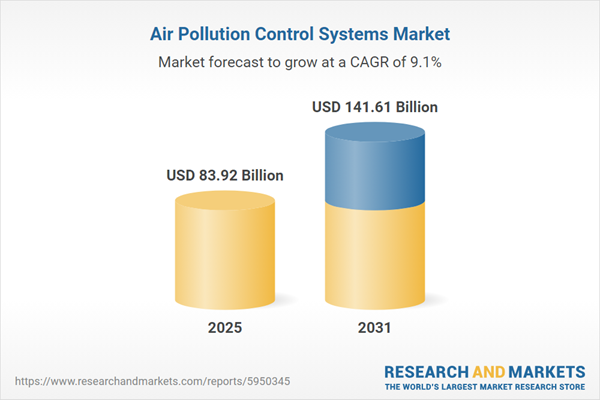

A recent study published in Environment International provides critical evidence on the adverse effects of prenatal exposure to air pollution on neonatal brain development. The research establishes a direct link between fine particulate matter (PM2.5) and delayed brain maturation in newborns, highlighting a significant challenge to achieving Sustainable Development Goal 3 (Good Health and Well-being) and SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities). The study investigated the complex role of PM2.5, which contains both toxic pollutants and essential trace elements, to understand its net impact on myelination during the critical prenatal period.

Methodology

The population-based study was conducted in Barcelona and involved a cohort of 93 neonates. The research methodology was designed to provide a comprehensive analysis of pollution exposure and its neurological impact.

- Exposure Assessment: Researchers developed advanced models to estimate daily PM2.5 concentrations at each mother’s residence. This was enhanced with personalized data on daily movements collected via smartphone applications, providing a precise measure of total exposure during the first (embryonic) and third (late fetal) trimesters.

- Neurological Assessment: Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) scans were performed on the infants at an average age of 29 days. These scans were used to quantify brain maturation through two key metrics: the total volume of myelinated white matter (global myelination) and the degree of myelination in the cerebral cortex.

Key Findings on Brain Maturation

The analysis revealed specific and time-dependent associations between PM2.5 exposure and brain development, underscoring the vulnerability of the fetal brain to environmental pollutants.

- First Trimester Impact: Higher exposure to PM2.5 during the first trimester was associated with lower levels of cortical myelination in newborns.

- Third Trimester Impact: Greater PM2.5 exposure during the third trimester was linked to a lower volume of global myelinated white matter.

- Source of Toxicity: The negative association with myelination was observed for both overall PM2.5 and its metallic trace elements (iron, copper, zinc). However, the effect of the metals was not statistically significant after accounting for the total PM2.5 concentration, suggesting the harm is caused by the general toxicity of the pollutant mixture rather than specific elements.

- Specificity of Effect: The study found no significant link between PM2.5 exposure and total brain volume, indicating that the pollution specifically interferes with the myelination process, a key indicator of brain maturation, rather than overall brain growth.

Implications for Sustainable Development Goals

The findings carry significant weight for public health policy and the global effort to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. The link between air quality and early-life development directly impacts several interconnected SDGs.

SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being

- The study demonstrates a clear environmental threat to Target 3.2, which aims to end preventable deaths of newborns and children under 5. By impairing brain maturation, air pollution poses a risk to healthy development from the earliest stage of life.

- Protecting pregnant women and their unborn children from air pollution is essential for ensuring healthy lives and promoting well-being for all ages, a cornerstone of SDG 3.

SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities

- The research, conducted in a major urban center, reinforces the urgency of Target 11.6: to reduce the adverse per capita environmental impact of cities, including by paying special attention to air quality.

- The findings validate the need for robust urban policies, such as low-emission zones, to create safe, resilient, and sustainable environments. Protecting the most vulnerable populations from environmental hazards is a critical component of making cities inclusive.

Conclusion and Policy Recommendations

This study provides compelling evidence that prenatal exposure to PM2.5 air pollution is associated with a slower rate of brain myelination in newborns. While the long-term consequences require further longitudinal research, these findings represent a clear call to action. To advance global health and sustainability targets, policies must prioritize the reduction of air pollution.

- Strengthen Air Quality Standards: Governments must adopt and enforce stricter air quality standards that align with public health evidence to protect vulnerable groups, including pregnant women and children.

- Enhance Urban Environmental Policies: Municipalities should expand and strengthen measures like low-emission zones to reduce traffic-related pollution, directly contributing to SDG 3 and SDG 11.

- Promote Further Research: Longitudinal studies are needed to track the developmental trajectories of children exposed to pollution in utero to determine if early delays in myelination lead to later cognitive or behavioral deficits.

Analysis of Sustainable Development Goals in the Article

1. Which SDGs are addressed or connected to the issues highlighted in the article?

The article primarily addresses two Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs):

- SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being: The core of the article focuses on the health impacts of environmental factors on human development. It specifically investigates the connection between a pregnant mother’s exposure to air pollution and the brain development of her newborn child, a fundamental aspect of ensuring healthy lives from the earliest stage. The study’s finding that PM2.5 exposure is “associated with lower levels of myelinated white matter, a key indicator of brain maturity,” directly relates to health outcomes.

- SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities: The research is set in an urban context (Barcelona) and explicitly links the health issue to urban air quality. The article discusses the need for “reducing air pollution in urban environments” and references policy measures like the “low-emission zone.” This connects the problem and potential solutions to the challenge of making cities inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable, particularly concerning environmental quality.

2. What specific targets under those SDGs can be identified based on the article’s content?

Based on the article’s content, the following specific targets can be identified:

-

SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being

- Target 3.2: “By 2030, end preventable deaths of newborns and children under 5 years of age…” While the article does not discuss mortality, it focuses on a critical aspect of neonatal health—brain maturation. The finding that pollution may cause a “slower rate of early myelination” addresses factors that can compromise a newborn’s healthy development, which is foundational to child survival and well-being.

- Target 3.9: “By 2030, substantially reduce the number of deaths and illnesses from hazardous chemicals and air, water and soil pollution and contamination.” This target is directly relevant. The entire study is about the health effects (“alterations in the myelination process”) caused by exposure to air pollution (PM2.5), which is a form of hazardous contamination.

-

SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities

- Target 11.6: “By 2030, reduce the adverse per capita environmental impact of cities, including by paying special attention to air quality…” The article directly supports this target by highlighting the adverse health impacts of poor air quality in Barcelona. The call to “continue controlling pollution levels” and the mention of the city’s “low-emission zone” underscore the focus on managing and improving urban air quality to protect vulnerable populations like pregnant women and newborns.

3. Are there any indicators mentioned or implied in the article that can be used to measure progress towards the identified targets?

Yes, the article mentions or implies specific indicators that can be used to measure progress:

-

Indicators for SDG 3 Targets

- Implied Indicator for Target 3.9: The article uses the “volume of myelinated white matter” and “cortical myelination” in newborns as a direct measure of the health impact of air pollution. This serves as a specific, measurable indicator of illness or adverse developmental effects resulting from pollution. The article calls it a “progressive indicator of brain maturation,” which is slowed by PM2.5 exposure.

-

Indicators for SDG 11 Targets

- Mentioned Indicator for Target 11.6: The official indicator for this target is the annual mean level of fine particulate matter (PM2.5). The article explicitly focuses on this pollutant, stating that researchers “estimated daily concentrations of PM2.5 and its metallic components at the mother’s home address.” This measurement of PM2.5 concentration is a direct indicator used to assess urban air quality.

4. Summary Table of SDGs, Targets, and Indicators

| SDGs | Targets | Indicators |

|---|---|---|

| SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being |

|

|

| SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities |

|

|

Source: psypost.org

What is Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0