The Marine Corps Americans Want Can’t Be Derailed by a Fake Crisis – War on the Rocks

Report on U.S. Marine Corps Strategic Reform and its Alignment with Sustainable Development Goals

Introduction: Institutional Reform for Global Peace and Security

An ongoing strategic transformation within the United States Marine Corps, known as Force Design, represents a significant effort to modernize the institution to meet contemporary and future security challenges. This reform initiative, while generating internal debate, is fundamentally aligned with the principles of SDG 16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions. By adapting its structure and capabilities, the Marine Corps aims to enhance its effectiveness in deterring conflict and maintaining stability, thereby contributing to the promotion of peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development.

The internal discourse surrounding Force Design, particularly the critiques from a group of retired officers, highlights the process of institutional accountability and the continuous effort to ensure the organization remains effective, resilient, and responsive to national and global security requirements. This process is essential for building and maintaining the “strong institutions” called for by SDG 16.

Adapting to a New Security Environment

The Changing Character of Warfare and the Imperative for Innovation (SDG 9)

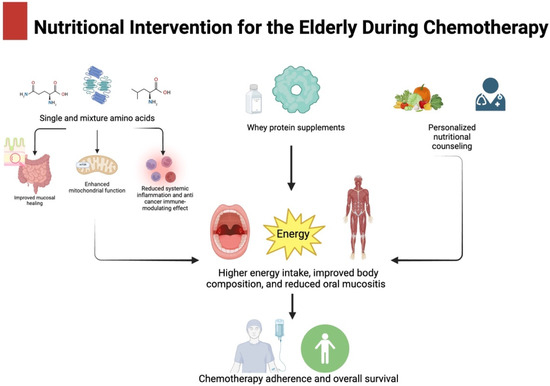

The strategic rationale for Force Design is rooted in an analysis of the changing character of modern warfare. This analysis recognizes that potential adversaries are increasingly leveraging advanced technologies and asymmetric tactics. This aligns with SDG 9: Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure, as the reforms are a direct response to technological advancements and necessitate significant innovation within the military institution.

Key characteristics of the contemporary security environment include:

- Increased reliance on long-range precision missiles and unmanned systems (drones).

- Integration of cyber operations, disinformation, and political subversion.

- Prominent use of deniable or semi-deniable forces, such as maritime militias and private military companies.

- A focus on contested maritime environments, particularly in key straits and island chains.

To address these challenges, the Marine Corps is pursuing institutional and technological innovations, developing resilient infrastructure and new operational concepts to ensure stability in these critical regions.

The Stand-In Force: Partnerships and Collaborative Security (SDG 17)

A central component of the reform is the “Stand-In Force” concept. This model involves positioning smaller, more agile, and technologically advanced Marine units within contested maritime spaces, operating in close collaboration with allies. This approach directly embodies the principles of SDG 17: Partnerships for the Goals, emphasizing the need for global partnerships to achieve security and development objectives.

The objectives of the Stand-In Force include:

- Acting as forward sentinels to provide persistent reconnaissance and early warning.

- Deterring aggression by complicating adversary planning and decision-making.

- Enabling joint and combined military operations in the event of a crisis.

- Strengthening the defensive capabilities of allies and partners through shared operations and training.

Recent events in the Black Sea and Red Sea, where asymmetric tactics have been used to disrupt maritime security, underscore the relevance of this concept. By developing capabilities to counter such disruptions, the Stand-In Force contributes to securing global commons, which is vital for international trade and economic stability, a key aspect of SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth.

Operational Priorities and Resource Allocation

Strategic Debate: The Marine Expeditionary Unit and the Stand-In Force

A current debate within the Marine Corps concerns the relative priority of the traditional Marine Expeditionary Unit (MEU) versus the new Stand-In Force. The MEU is a versatile, globally responsive formation, while the Stand-In Force is specialized for high-end conflict in contested maritime zones. This debate over resource allocation and strategic focus is critical for ensuring the institution’s long-term effectiveness and its contribution to global peace (SDG 16).

Prioritizing the Stand-In Force aligns with strategic guidance to prepare for peer-level deterrence. However, maintaining a robust MEU capability is seen as essential for responding to a wider range of global crises. Balancing these priorities requires careful strategic planning to ensure modernization efforts are complementary and do not divert resources from the most critical tasks related to maintaining international peace and security.

The Littoral Mobility Challenge: A Call for Sustainable and Resilient Infrastructure (SDG 9)

A significant challenge facing the Marine Corps is its dependence on a limited number of large, traditional amphibious ships. The Force Design concept, particularly the Stand-In Force, requires a new approach to maritime mobility in contested littoral environments. This has led to calls for a new family of vessels that are faster, stealthier, and more survivable.

Proposed solutions align with SDG 9 by focusing on developing new, innovative, and resilient infrastructure:

- Medium Landing Ship: A smaller vessel capable of landing equipment on austere shorelines.

- Low-Observable Fast Transports: Stealthy vessels designed to move forces quickly through contested waters.

- Uncrewed Screening and Deception Vessels: Autonomous systems to confuse enemy surveillance and protect manned platforms.

- Autonomous Resupply Vessels: Unmanned, low-profile systems for logistics in high-threat environments, inspired by commercial innovations.

Developing these capabilities, potentially under direct Marine Corps programmatic control, would represent a major institutional innovation, enhancing the service’s ability to contribute to stability in vital maritime zones, which are crucial for the global environment and economy (linking to SDG 14: Life Below Water and SDG 8).

Conclusion: A Future-Oriented Institution for Global Stability

The U.S. Marine Corps’ Force Design reforms are a necessary adaptation to the modern security landscape. By focusing on innovation (SDG 9), strengthening partnerships (SDG 17), and enhancing its ability to deter major conflict, the service is working to fulfill its role as a strong and effective institution for peace (SDG 16). The ongoing internal debates, while contentious, are a vital part of this institutional evolution. The ultimate goal is to create a Marine Corps that is equipped not only to respond to crises but to proactively contribute to a stable and secure international order, which is the foundation for achieving all Sustainable Development Goals.

Relevant Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

- SDG 16: Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions

- SDG 9: Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure

- SDG 17: Partnerships for the Goals

- SDG 14: Life Below Water

Identified SDG Targets

-

SDG 16: Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions

-

Target 16.1: Significantly reduce all forms of violence and related death rates everywhere.

The article discusses military reforms, such as Force Design 2030, which are primarily aimed at strengthening deterrence to prevent large-scale conflicts with adversaries like China. The text states, “These changes strengthen deterrence and, if deterrence fails, help ensure victory.” The primary goal of deterrence is to prevent war, which is the most extreme form of violence with the highest death rates.

-

Target 16.6: Develop effective, accountable and transparent institutions at all levels.

The core of the article is a debate about making the U.S. Marine Corps a more effective and accountable institution. The reforms are a response to “congressional scrutiny, presidential policy, and secretary of defense guidance.” The author praises the Marine Corps for “exercising fiscal discipline, and adapting for the future of warfare,” which are hallmarks of an effective and accountable institution. The critique of the “Chowderites” is framed as “anti-institutional” because it ignores strategic directives and policy.

-

Target 16.a: Strengthen relevant national institutions… to prevent violence and combat terrorism and crime.

The article references the Marine Corps’ role in the “Global War on Terror,” fighting “against the self-proclaimed Islamic State in Syria,” and its historical ability to launch assaults “against a terrorist group.” This aligns with the target of strengthening institutional capacity to combat terrorism.

-

Target 16.1: Significantly reduce all forms of violence and related death rates everywhere.

-

SDG 9: Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure

-

Target 9.5: Enhance scientific research, upgrade the technological capabilities of industrial sectors…

The article extensively details the need for technological innovation and upgrading the Marine Corps’ capabilities. It calls for “equipping America’s Marine littoral regiments with drones and missiles” and developing a “new family of ships to operate in littoral environments.” Specific innovations mentioned include “uncrewed littoral screening and deception vessels,” “low-observable fast transports,” and logistics vessels inspired by “narco-submarines,” all of which represent a significant upgrade of technological capabilities to meet modern threats.

-

Target 9.5: Enhance scientific research, upgrade the technological capabilities of industrial sectors…

-

SDG 17: Partnerships for the Goals

-

Target 17.16: Enhance the global partnership for sustainable development, complemented by multi-stakeholder partnerships…

The article repeatedly emphasizes the importance of working with allies. The strategy involves placing Marine units “shoulder to shoulder with allies and partners” and fighting “alongside allies and partners from their territory and beyond.” This highlights the necessity of strong international partnerships for maintaining regional security and stability, which is a precondition for sustainable development.

-

Target 17.6: Enhance… international cooperation on and access to science, technology and innovation…

The article provides a concrete example of technology-focused partnerships by noting that the United States “funded a purchase of a smaller variant [of the Devil Ray USV] by the Philippines.” This action represents a transfer of technology and capacity-building with a key partner nation to enhance shared security objectives.

-

Target 17.16: Enhance the global partnership for sustainable development, complemented by multi-stakeholder partnerships…

-

SDG 14: Life Below Water

-

Target 14.c: Enhance the conservation and sustainable use of oceans and their resources by implementing international law…

The article’s focus on securing “key maritime terrain,” “littoral zones,” and “key shipping lanes” is directly related to ensuring freedom of navigation and maritime security. It mentions threats to shipping from the Houthis and Ukraine’s success in enabling it “to sustain critical maritime trade.” Securing these maritime spaces is essential for enforcing international law at sea (like UNCLOS) and enabling the safe, lawful, and sustainable use of ocean resources.

-

Target 14.2: Sustainably manage and protect marine and coastal ecosystems…

The discussion of conflict in key maritime geographies like the South China Sea, where China employs a “maritime militia,” implicitly touches upon threats to marine ecosystems. These militias are often associated with activities like illegal fishing and environmental destruction that undermine the sustainable management of marine resources. Military presence to deter such illegal actions contributes to the protection of these ecosystems.

-

Target 14.c: Enhance the conservation and sustainable use of oceans and their resources by implementing international law…

Implied Indicators for Measuring Progress

-

SDG 16: Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions

- Institutional Effectiveness and Accountability (Target 16.6): Progress can be measured by the alignment of the Marine Corps’ force structure with strategic guidance from civilian leadership. The article implies that the successful implementation of Force Design, praised by “Congress and across multiple presidential administrations,” is a key indicator. Another indicator mentioned is “fiscal discipline.”

- Institutional Health (Target 16.6): The article points to the Marine Corps’ relative success in recruitment (“struggled much less than any of the other services during the recent recruiting crisis”) as an indicator of institutional health and public support.

- Deterrence Strength (Target 16.1): While difficult to quantify, the perceived strength of the military deterrent is an implied indicator. The article argues that the reforms “strengthen deterrence,” suggesting that the ability to prevent adversaries from initiating conflict is a measure of success.

-

SDG 9: Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure

- Technological Advancement (Target 9.5): Progress is indicated by the development, testing, and fielding of new technologies. The article cites the testing of “uncrewed, low-profile vessels… in Okinawa,” the fielding of the Navy’s “Common Unmanned Surface Vehicle,” and the redesignation of regiments into “Marine Littoral Regiments” equipped with new systems as concrete indicators of technological upgrades.

-

SDG 17: Partnerships for the Goals

- Strength of Alliances (Target 17.16): Indicators include the frequency and complexity of joint operations and deployments with allies, such as the “rotational Marine deployments to allied soil in the Indo-Pacific” and training exercises like those with the Philippines.

- Capacity-Building Support (Target 17.6): A direct indicator is the provision of military technology and funding to partners, such as the U.S.-funded “purchase of a smaller variant [USV] by the Philippines.”

-

SDG 14: Life Below Water

- Maritime Security (Target 14.c): An indicator is the ability to keep strategic waterways open for commerce. The article contrasts the Houthi threat to “key shipping lanes” with Ukraine’s success in enabling it “to sustain critical maritime trade,” implying that the security of these routes is a measurable outcome.

Summary of Findings

| SDGs | Targets | Indicators Identified in the Article |

|---|---|---|

| SDG 16: Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions |

16.1: Reduce all forms of violence.

16.6: Develop effective, accountable and transparent institutions. 16.a: Strengthen national institutions to prevent violence and combat terrorism. |

– Perceived strength of military deterrence to prevent large-scale war. – Alignment of institutional reforms with strategic directives from civilian leadership. – Evidence of fiscal discipline. – Success rates in military recruitment compared to other services. – Documented operations against terrorist organizations like the Islamic State. |

| SDG 9: Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure | 9.5: Enhance scientific research, upgrade technological capabilities. |

– Development and testing of new military hardware (e.g., uncrewed vessels, drones, missiles). – Fielding of new platforms like the Medium Landing Ship and Common Unmanned Surface Vehicle. – Reorganization of military units (e.g., Marine Littoral Regiments) to integrate new technologies. |

| SDG 17: Partnerships for the Goals |

17.16: Enhance the global partnership for sustainable development.

17.6: Enhance international cooperation on science, technology and innovation. |

– Number and scope of rotational deployments and joint exercises with allied nations. – Specific instances of technology transfer or funding for partners (e.g., providing USVs to the Philippines). |

| SDG 14: Life Below Water |

14.c: Enhance the conservation and sustainable use of oceans through international law.

14.2: Sustainably manage and protect marine and coastal ecosystems. |

– Ability to keep critical maritime trade routes and shipping lanes open and secure. – Presence to deter illegal activities (e.g., by maritime militias) that harm marine environments. |

Source: warontherocks.com

What is Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0