The FOSTA-SESTA Fallout Is About to Get Worse

The FOSTA-SESTA Fallout Is About to Get Worse The Nation

Feature / September 16, 2023

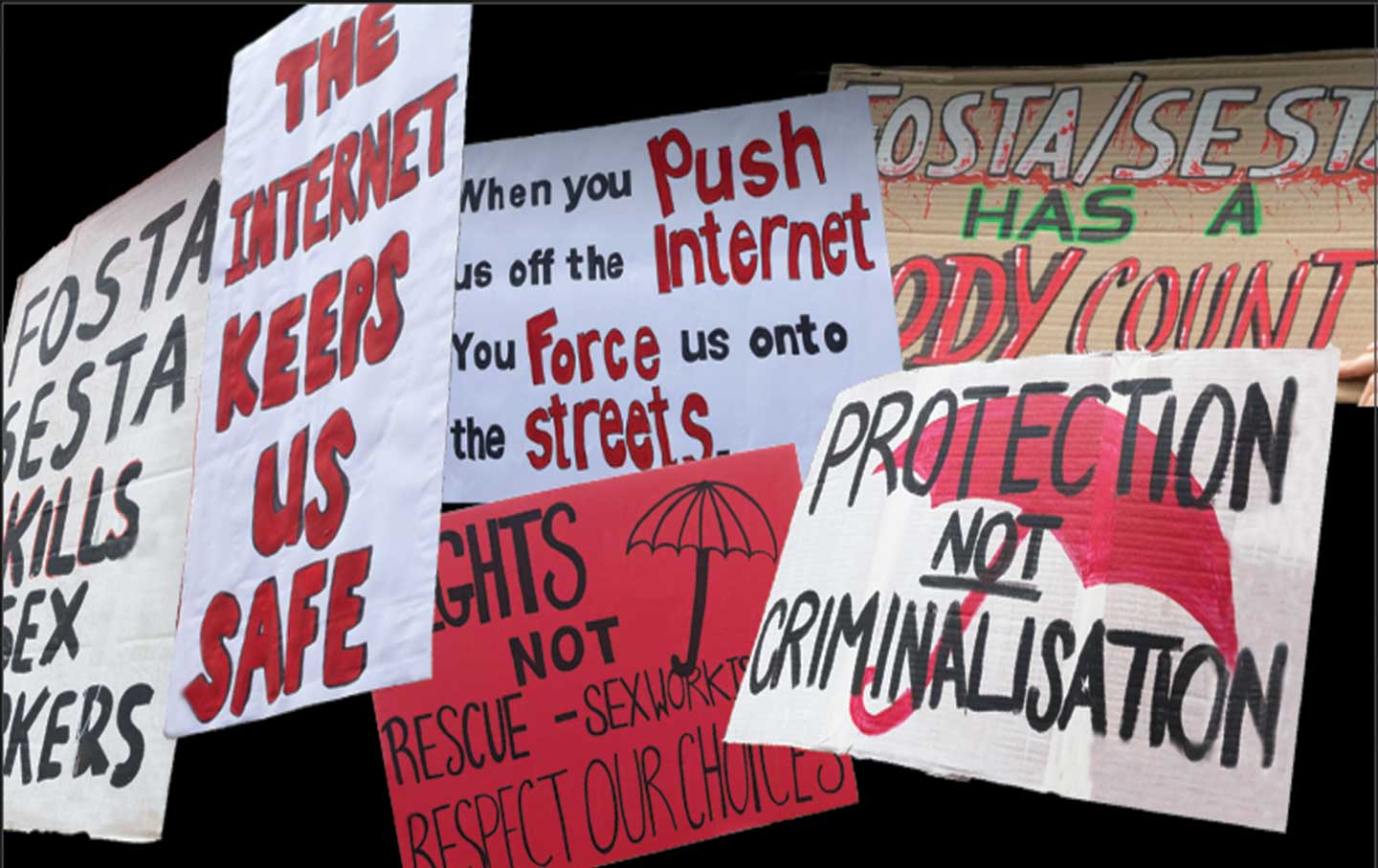

The Fosta-Sesta Fallout: How Legislation Endangers Sex Workers and Free Expression Online

In April of 2018, when Donald Trump signed the Allow States and Victims to Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act, sex workers and civil liberties groups sounded the alarm. The legislation—known as FOSTA-SESTA because it incorporated parts of the Stop Enabling Sex Traffickers Act—rescinded legal immunity, previously granted by Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, for online platforms that host content that “promotes or facilitates prostitution.” The legislation was sold to Congress and the public as a way of holding websites accountable for sex trafficking (in a celebrity-studded PSA, the comedian Amy Schumer declared that “buy[ing] a child for sex” is “as easy as ordering a pizza”), and it found support across the political spectrum. But from the beginning, trafficking survivors themselves warned that FOSTA-SESTA would endanger voluntary sex workers and restrict free expression on the Internet. Along with LGBTQ groups, they argued that the law wouldn’t address the root causes of child trafficking (such as poverty and youth homelessness) and were worried that it would scare website operators into censoring unrelated sexual content.

The Impact of FOSTA-SESTA

From the outset, there was ample warning about FOSTA-SESTA, even if the law had noble intentions. The Justice Department raised objections before it even passed, concerned that its language extended beyond trafficking to cover “commercial sex transactions involving consenting adults,” which was of “minimal federal interest.” Freedom Network USA, the largest national organization of anti-trafficking social service providers and advocates, also opposed this aspect of the legislation, stating that “further criminalizing consensual commercial sex work, where there is no force, fraud or coercion, is no way to protect victims.” (Sex trafficking survivors typically favor prevention strategies that are structural in nature, like affordable housing, universal basic income, a living wage, and the expunging of criminal records.) Concerned with the threat of censorship, the ACLU warned that the law posed a “real and significant” risk to the “vibrancy of the Internet as a driver of political, artistic, and commercial communication.” But all of these considerations went unheeded, and FOSTA-SESTA sailed through Congress.

Now, five years later, reports from legal scholars, researchers, and the Government Accountability Office conclude that the law has been counterproductive at best and deadly at worst, confirming the early fears. Accurate data on sex trafficking is notoriously elusive, but by most accounts, online sex trafficking remains rampant; its facilitation has simply moved overseas or underground, where law enforcement cannot subpoena the information needed to apprehend perpetrators or locate and aid victims. A 2022 study by the Rhode Island chapter of the sex worker advocacy group COYOTE revealed that 64 percent of trafficking survivors in the sex trade have experienced an increase in force or coercion since the law took effect, making its “real world effects…completely contrary to its stated intent.” As attorney Emily Morgan observed in The Northwestern Law Review, citing the work of legal scholar A.F. Levy, FOSTA-SESTA—in failing “to provide real relief to its intended beneficiaries”—amounts to a form of “pageantry.” To date, there has been just one criminal conviction under the law. A group of free speech advocacy and human rights organizations recently sued to overturn FOSTA-SESTA on First Amendment grounds. In July, the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals upheld it but clarified and limited its far-reaching scope; whether this change will restore censored content and undo five years of damage remains to be seen.

Unfortunately, the vindication of FOSTA-SESTA’s critics has not stopped lobbyists and politicians from implementing more ways to censor sexual speech online. The unlikely ideological alliance of anti-sex-work feminists, religious fundamentalists, and modern-day Anthony Comstocks has existed since at least the 1980s, when radical feminists joined forces with right-wing conservatives to praise the findings of Ronald Reagan’s Meese Commission on Pornography. Today, they stoke the flames of a moral panic that conflates a range of commercial adult-oriented services with abuse. In this war against putative commercial sexual exploitation and child endangerment, the erosion of sex workers’ rights and freedom of speech has been collateral damage.

The Impact on Sex Workers

Sex workers have meticulously documented the ways that FOSTA-SESTA has jeopardized their safety. The worker collective Hacking//Hustling conducted peer-led research on the impact of the law 18 months after it was signed. Using online surveys and personal interviews with a range of sex workers in varying circumstances, it found that FOSTA-SESTA severely curtailed their ability to work indoors, work independently, and share support or harm-reduction resources (such as “bad date” blacklists and free health services) with their communities. With their ability to find and screen clients online restricted, some reported turning to pimps or other predatory third parties and engaging in street-based work, which is exponentially more dangerous. The passage of FOSTA-SESTA and the ensuing loss of advertising sites have resulted in an overall increase in economic instability and in violence from clients.

The Impact on Free Expression Online

In addition to these significant material harms, the law has had a chilling effect on online speech for everyone. To avoid serious criminal and civil liabilities, many websites and apps now overregulate all erotic material—much of which is unrelated to sex work. In the immediate wake of FOSTA-SESTA, risk-averse platform operators removed a wide array of content related to human sexuality. According to the Woodhull Freedom Foundation and the Electronic Frontier Foundation, organizations that track sexual and online censorship, respectively, FOSTA-SESTA has led to the elimination of age-appropriate sexual health and education resources, and it remains unclear whether the recent Circuit Court ruling can or will restore them. Materials that refer to “sexual pleasure,” reproductive organs, or slang terms for body parts have been censored on social media platforms and e-mail services, as have advertisements for sex toys, sex counselors, and at least one licensed massage therapist. Facebook, Tumblr, Reddit, and Instagram now strictly limit the type of language and images that users can post, while Craigslist removed its entire personals section in response to the law.

The Future of Online

SDGs, Targets, and Indicators Analysis

1. Which SDGs are addressed or connected to the issues highlighted in the article?

- SDG 5: Gender Equality

- SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth

- SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities

- SDG 16: Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions

The article discusses the negative impact of legislation on sex workers and the restriction of free expression on the Internet. These issues are connected to SDG 5, which aims to achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls. The legislation discussed in the article disproportionately affects women who engage in voluntary sex work and restricts their rights and safety.

Furthermore, the article highlights the economic instability and increased violence faced by sex workers as a result of the legislation. This is relevant to SDG 8, which focuses on promoting sustained, inclusive, and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment, and decent work for all.

The article also touches on the issue of reduced access to online resources and censorship, which can contribute to inequalities. This aligns with SDG 10, which aims to reduce inequalities within and among countries.

Lastly, the article discusses the impact of the legislation on freedom of speech and the need for justice and strong institutions. This relates to SDG 16, which seeks to promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all, and build effective, accountable, and inclusive institutions at all levels.

2. What specific targets under those SDGs can be identified based on the article’s content?

- Target 5.1: End all forms of discrimination against all women and girls

- Target 8.7: Take immediate and effective measures to eradicate forced labor, end modern slavery and human trafficking, and secure the prohibition and elimination of the worst forms of child labor

- Target 10.3: Ensure equal opportunity and reduce inequalities of outcome, including through eliminating discriminatory laws, policies, and practices

- Target 16.10: Ensure public access to information and protect fundamental freedoms, in accordance with national legislation and international agreements

Based on the article’s content, the targets listed above are relevant to the issues discussed. The legislation discussed in the article contributes to discrimination against women and girls engaged in sex work, which goes against Target 5.1.

The legislation also affects the rights and safety of sex workers, which relates to Target 8.7, as it involves forced labor and human trafficking. Additionally, the economic instability faced by sex workers aligns with Target 8.7’s aim to secure the prohibition and elimination of the worst forms of child labor.

The restrictions on online speech and censorship mentioned in the article are connected to Target 16.10, which emphasizes the importance of protecting fundamental freedoms and ensuring public access to information.

Lastly, the impact of the legislation on sex workers’ rights and freedom of speech highlights the need to address discriminatory laws, policies, and practices, as stated in Target 10.3.

3. Are there any indicators mentioned or implied in the article that can be used to measure progress towards the identified targets?

- Indicator 5.1.1: Whether or not legal frameworks are in place to promote, enforce, and monitor equality and non-discrimination on the basis of sex

- Indicator 8.7.1: Proportion and number of children aged 5-17 years engaged in child labor, by sex and age group

- Indicator 10.3.1: Proportion of people reporting having personally felt discriminated against or harassed in the previous 12 months on the basis of a ground of discrimination prohibited under international human rights law

- Indicator 16.10.2: Number of countries that adopt and implement constitutional, statutory, and/or policy guarantees for public access to information

The article does not explicitly mention specific indicators, but the following indicators can be used to measure progress towards the identified targets.

Indicator 5.1.1 can be used to assess whether legal frameworks are in place to promote, enforce, and monitor equality and non-discrimination on the basis of sex, specifically focusing on the rights and safety of sex workers.

Indicator 8.7.1 can measure the proportion and number of children engaged in child labor, which is relevant to the discussion of forced labor and exploitation in the context of sex trafficking.

Indicator 10.3.1 can be used to measure the proportion of people who report experiencing discrimination or harassment based on a ground of discrimination prohibited under international human rights law, including discrimination faced by sex workers.

Indicator 16.10.2 can assess the number of countries that adopt and implement constitutional, statutory, and/or policy guarantees for public access to information, particularly in relation to online speech and censorship.

4. Table: SDGs, Targets, and Indicators

| SDGs | Targets | Indicators |

|---|---|---|

| SDG 5: Gender Equality | Target 5.1: End all forms of discrimination against all women and girls | Indicator 5.1.1: Whether or not legal frameworks are in place to promote, enforce, and monitor equality and non-discrimination on the basis of sex |

| SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth | Target 8.7: Take immediate and effective measures to eradicate forced labor, end modern slavery and human trafficking, and secure the prohibition and elimination of the worst forms of child labor | Indicator 8.7.1: Proportion and number of children aged 5-17 years engaged in child labor, by sex and age group |

| Target 8.7: Take immediate and effective measures to eradicate forced labor, end modern slavery and human trafficking, and secure the prohibition and elimination of the worst forms of child labor | Indicator 8.7.1: Proportion and number of children aged 5-17 years engaged in child labor, by sex and age group | |

| SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities | Target 10.3: Ensure equal opportunity and reduce inequalities of outcome, including through eliminating discriminatory laws, policies, and practices | Indicator 10.3.1: Proportion of people reporting having personally felt discriminated against or harassed in the previous 12 months on the basis of a

Behold! This splendid article springs forth from the wellspring of knowledge, shaped by a wondrous proprietary AI technology that delved into a vast ocean of data, illuminating the path towards the Sustainable Development Goals. Remember that all rights are reserved by SDG Investors LLC, empowering us to champion progress together. Source: thenation.com

Join us, as fellow seekers of change, on a transformative journey at https://sdgtalks.ai/welcome, where you can become a member and actively contribute to shaping a brighter future.

|