For the first time ever, Taliban reps were invited to the big U.N. climate conference

Afghanistan participated in the UN climate conference COP29 as observers, despite the Taliban not being recognized as its official government, to discuss environmental protection and climate change. The country faces severe climate impacts, including droughts, flash floods, and water shortages, which have displaced thousands and worsened poverty, with international climate funding largely suspended since 2021. Experts stress the need for innovative mechanisms to deliver climate aid directly to Afghan communities, warning that isolating Afghanistan could exacerbate regional and global climate challenges.

For the first time since the Taliban takeover in 2021, a delegation from Afghanistan has been invited to the United Nations signature climate conference: the 29th Conference of Parties (COP).

Following U.N. protocol, this year's host nation — Azerbaijan — issued the invite.

It's not a full-blown invitation. Because the U.N. does not recognize the Taliban as the official government of Afghanistan due to its repressive policies, the Afghan delegates — members of the National Environmental Protection Agency (NEPA — cannot participate in decision-making events.

Nonetheless, the Taliban has said it is eager to participate. "The Afghan delegation will discuss strengthening international cooperation in the field of environmental protection and climate change," stated a Taliban press release prior to the U.N. event.

Afghan climate scientists and activists, even those critical of the Taliban, welcome this development. "I consider it a very important move because it paves the path to the negotiation with climate change funds, which halted their [Afghan] projects in the past three years," says Assem Mayar, a water resources expert and former lecturer at Kabul Polytechnic University.

"Afghanistan is not officially in the agenda, but having NEPA delegates as observers makes a difference," says Abdulhadi Achakzai, a climate activist with a Kabul-based environmental nonprofit who participated in the summit as an observer.

"Their participation initiates a trust-building effort between international stakeholders," he says, which is imperative if the world "is committed to combating the climate crisis."

A hard-hit country

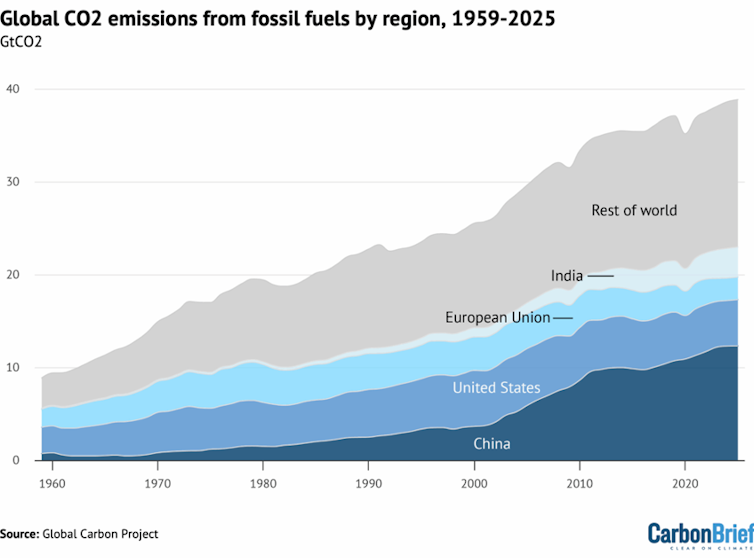

Afghanistan is among the countries worst impacted by climate change, according to the U.N.; droughts and extreme temperatures have displaced hundreds of thousands of people in recent years.

In 2019, Afghanistan was ranked sixth among countries most affected by climate impacts on the Global Climate Risk Index. And it is among the least prepared to cope with the crisis according to the Notre Dame Global Adaptation Index.

And funding from international groups has been largely halted — part of the sanctions levied to protest Taliban policies that restrict human rights and women's rights.

Since the Taliban takeover, Mayar said climate adaptation projects worth $826 million have been suspended, reducing the capacity of Afghans to respond to increasing climate disasters, including irrigation projects and renewable energy.

Meanwhile, climate shocks have continued to batter Afghans. The country is currently experiencing its third consecutive drought in three years, punctuated by periods of deadly flash floods. According to U.N. data, about 120,000 people were affected by flash flooding and mudslides across the country so far this year.

More specifically, extreme weather — including droughts, extreme temperature, floods, landslides, avalanches and storms— displaced at least 38,000 people in the first half of this year. Save The Children reports about half of those were children.

"Mass migration is, in fact, one major concern and consequence of climate shocks," says Najibullah Sadid, an Afghan climate researcher from the University of Stuttgart. "People will abandon their land and even the country in search of livelihood."

The poppy problem

Severe droughts can also disrupt agriculture, which is the primary occupation in Afghanistan, driving farmers to turn to drought-resistant poppy cultivation instead of food crops. Poppy crops fetch higher prices, and so despite the Taliban's ban, Afghanistan has been among the leading producers.

Sadid says he worries if more fields are dedicated to growing poppies instead of food crops, the food shortage will only worsen.

The majority of the country already lives in poverty. And as climate change is expected to bring increasingly frequent and severe disasters, many Afghans face serious risk.

Achakzai hopes to communicate the urgency of the crisis to stakeholders at the COP summit, which ends on Friday. Climate activists from Afghanistan organized a side event on Wednesday, where Afghan scientists and civilians spoke about the climate stresses facing Afghans.

Various international agencies attended, says Achakzai, who observed some positive changes in international stakeholders' attitudes towards Afghanistan.

"We hope the participants were [persuaded into] thinking that they can work with the Taliban to fight against the climate change crisis," he says.

Running out of water

Extreme drought has exacerbated the challenge of finding drinking water in many communities, Achakza says. "Underground water tables, which most Afghans rely on, are drying faster than they can be replenished."

In a survey in Kabul conducted by Achakzai's organization, Environmental Protection, Training and Development Organization, researchers found that many communities were digging deeper wells to access groundwater — the primary source of water in the Afghan capital.

Additionally, the study found that many people had migrated to Kabul, abandoning their land and agriculture due to lack of water. But in the city, they find that water isn't exactly plentiful.

An October 2022 feasibility report from the Afghan Ministry of Water and Energy confirmed that the current underground water levels only meet about 40% of the city's expanding needs.

As a result, families, especially children, spend considerable time and effort to procure water, "often having to walk for miles everyday, only to find water in contaminated sources or buy them from private tankers," Achakzai says.

The next year is predicted to be drier than average, Mayar says, "and will result in more droughts in the country." A USAID-funded global network called the Famine Early Warning Systems confirmed this prediction with below average precipitation expected in coming months.

What next for Afghanistan?

With these predictions of prolonged droughts, Achakzai says it's imperative that the international community work to engage the current Afghan government to mitigate the impact of climate change.

Mayar agrees it's critical for the world to find a way to work with or around the Taliban because the loss of international aid has been devastating. The U.S., for instance, reduced its financial support to humanitarian projects in the country from from $1.26 billion in 2022 to $377 million in 2023. What's more, many countries limit aid that can be sent to Afghanistan to only humanitarian needs and won't fund development projects.

Mayar says developing a decentralized system that doesn't require Taliban involvement or approval to deliver aid could help support much-needed projects in the country.

"I propose the accreditation of [Afghan] national NGOs [by international climate fund donors] to receive and implement projects within communities," he says. "In a scenario where the government isn't recognized, such a mechanism could be very helpful in ensuring climate finances reach those affected."

The alternative — isolating Afghanistan from climate action — is grim, says these Mayar. "If we fail to facilitate a mechanism to help these communities, not only will the Afghan civilians bear the heaviest cost of climate change, but the impact of it will be felt across its borders."

Sadid agrees. "If the world is sincere with Afghans, they will find a way to deliver climate funds to Afghanistan, as they found ways to deliver emergency aid in the last three years," he said, adding that "ignoring Afghanistan's climate crisis could prove expensive to the world."

Ruchi Kumar is a journalist who reports on conflict, politics, development and culture in India and Afghanistan. She tweets at @RuchiKumarRuchi Kumar is a journalist who reports on conflict, politics, development and culture in India and Afghanistan. She tweets at @RuchiKumar

What is Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0

;Resize=620#)