What’s desertification? Experts hopeful devastating trend can be reversed

Desertification, the degradation of drylands due to climate change and poor land management, affects 40% of the world's land and 3.2 billion people, threatening biodiversity, livelihoods, and global ecosystems. The upcoming UNCCD COP16 in Riyadh aims to accelerate land restoration, combat droughts, promote sustainable land use, and unlock economic opportunities, showcasing global efforts to reverse this critical trend.

On 2 December, countries from around the world will meet in Riyadh under the auspices of the UN Convention to Combat Desertification, (UNCCD) to discuss how to turn the corner from degradation to regeneration.

Here are five things you need to know about desertification and why the world needs to stop treating the planet like dirt to protect the productive land which supports life on Earth.

No life without land

It is perhaps to state the obvious, but without healthy land there can be no life. It feeds, clothes and shelters humanity.

It provides jobs, sustains livelihoods and is the bedrock of local, national and global economies. It helps to regulate climate and is essential for biodiversity.

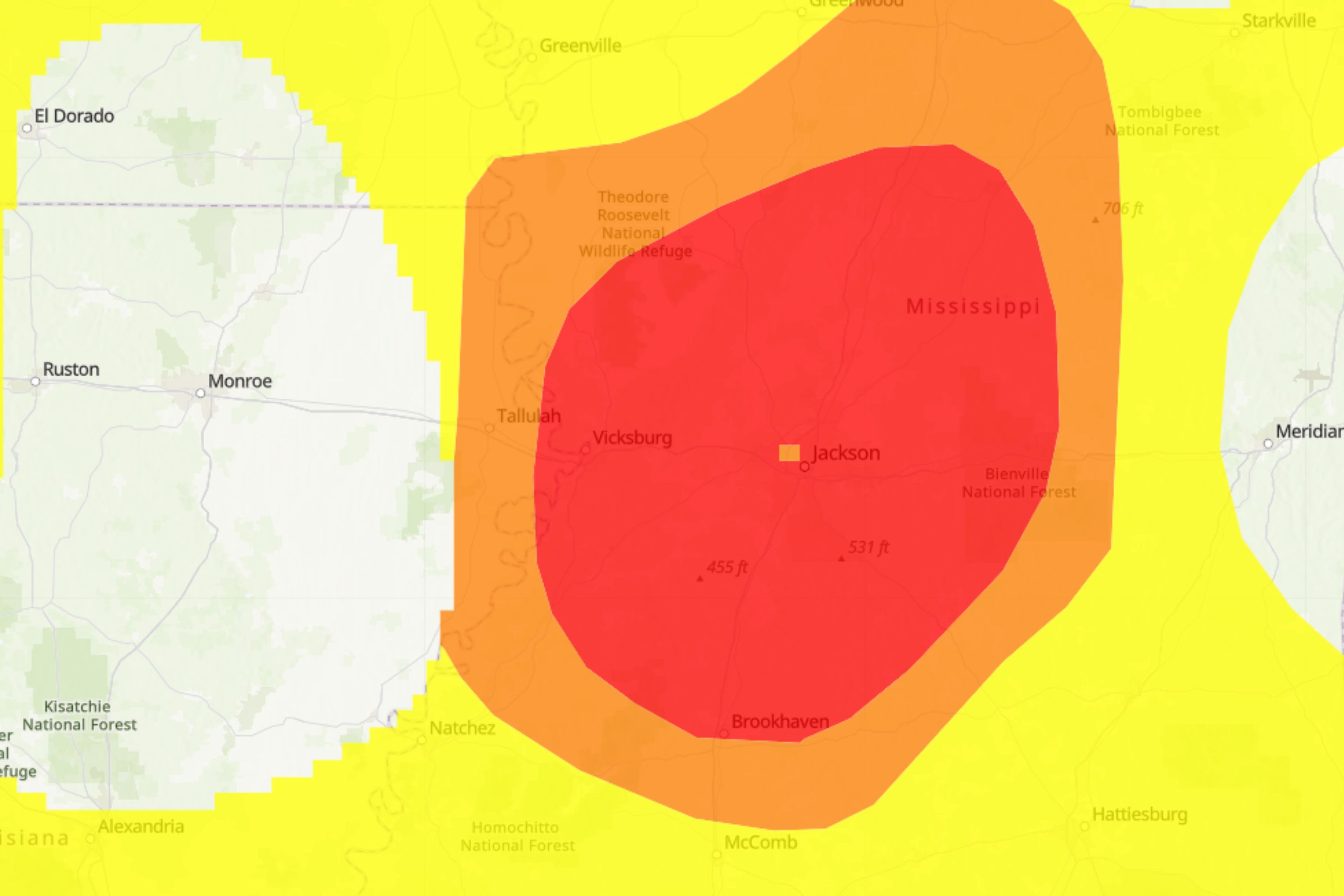

Despite its importance to life as we know it, up to 40 per cent of the world’s land is degraded, affecting around 3.2 billion people; that’s almost half of the global population.

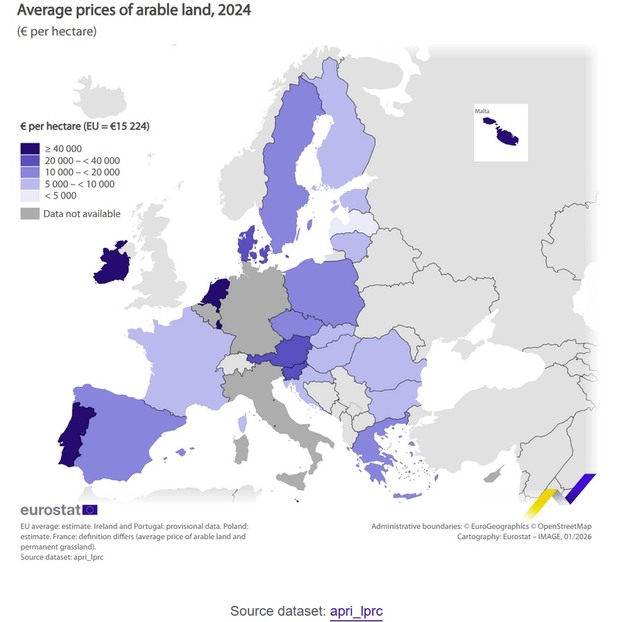

From deforested mountains in Haiti, to the gradual disappearance of Lake Chad in the Sahel and the drying up of productive lands in Georgia in eastern Europe, land degradation affects all parts of the world.

It is not an exaggeration to say our very future is at stake if our land does not stay healthy.

Degraded land

Desertification, the process by which land is degraded in typically dry areas, results from various factors, including climatic variations and human activities, such as over-farming or deforestation.

100 million hectares (or one million square kilometres), that’s the size of a country like Egypt, of healthy and productive land is lost each year.

The soils on these lands which can take hundreds of years to form are being depleted, often by extreme weather.

Droughts are hitting harder and more often, three out of four people in the world are projected to face water scarcity by 2050.

Temperatures are increasing due to climate change further driving extreme weather events, including droughts and floods, adding to the challenge of keeping land productive.

Land loss and climate

There is clear evidence that land degradation is interconnected with broader environmental challenges like climate change.

Land ecosystems absorb one-third of human CO2 emissions, the gas that is driving climate change. However, poor land management threatens this critical capacity, further compromising efforts to slow down the release of these harmful gasses.

Deforestation, which contributes to desertification, is on the rise, with only 60 per cent of the world's forests still intact, falling below what the UN calls the “safe target of 75 per cent.”

What needs to be done? – the ‘moonshot moment’

The good news is that humankind has the knowhow and power to bring land back to life, turning degradation into restoration.

Robust economies and resilient communities can be cultivated as the impacts of devastating droughts and destructive floods are tackled.

Crucially, it is the people who depend on land who should have the biggest say in how decisions are made.

UNCCD says that to “deliver a moonshot moment for land,” 1.5 billion hectares of degraded lands need to be restored by 2030.

And this is happening already with farmers adopting new techniques in Burkina Faso, environmentalists in Uzbekistan planting trees to eliminate salt and dust emissions and activists protecting the Philippines capital, Manila, from extreme weather by regenerating natural barriers.

What can be achieved in Riyadh

Policy makers, experts, the private and civil society sectors as well as youth will come together in Riyadh with a series of goals, including:

- Accelerate restoration of degraded land by 2030 and beyond

- Boost resilience to intensifying droughts and sand and dust storms

- Restore soil health and scale up nature-positive food production

- Secure land rights and promote equity for sustainable land stewardship

- Ensure that land continues to provide climate and biodiversity solutions

- Unlock economic opportunities, including decent land-based jobs for youth

What is Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0