‘I’m gonna O.J. you’: How the Simpson case changed perceptions — and the law — on domestic violence

'I'm gonna O.J. you': How the Simpson case changed perceptions — and the law — on domestic violence Los Angeles Times

Sustainable Development Goals and Domestic Violence in Los Angeles

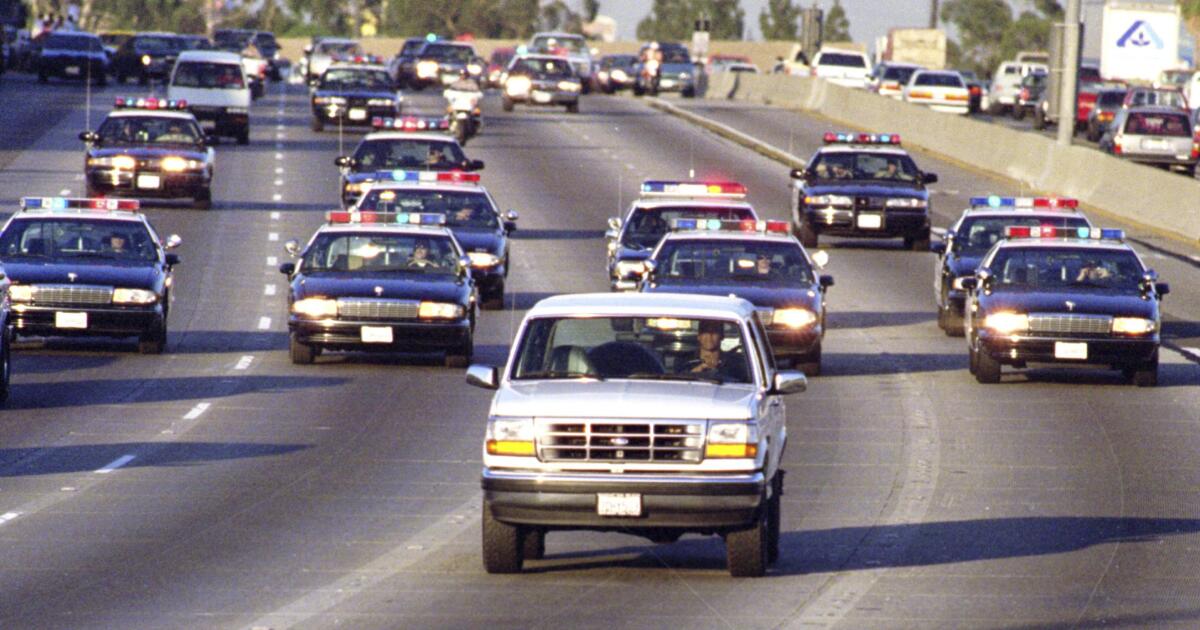

It wasn’t long after the televised spectacle of O.J. Simpson fleeing a phalanx of police cars in a slow-moving white Ford Bronco on June 17, 1994, that batterers across Los Angeles adopted a bone-chilling new threat.

I’m gonna O.J. you.

“We all heard it working with our clients,” said Gail Pincus, executive director of the Domestic Abuse Center in Los Angeles. “I heard it directly from the abusers. It was a form of intimidation, of silencing and getting compliance from their victims.”

Abuse survivors, meanwhile, flooded rape and battery hotlines and shelters, telling advocates: I don’t want to be the next Nicole.

The phone “was almost off the hook,” said Patti Giggans, executive director of Peace over Violence, then called the Los Angeles Commission on Assaults Against Women. “We were overloaded.”

“People were reaching out for help; they wanted to know, ‘Could that be me? Could that happen to me?’” she said. “It was a revelation that somebody could die.”

The Impact of the O.J. Simpson Case

For the American public, the slayings of Simpson’s ex-wife, Nicole Brown Simpson, and her friend Ronald Goldman were practically inescapable in those days. An estimated 95 million people watched the Bronco chase on television. Some 150 million tuned in for the verdict in 1995, when Simpson was acquitted.

The killings took place at a pivotal moment for domestic violence in California and the United States, catapulting what had long been considered a private problem into the public sphere.

“That murder captivated people. You could not escape from it,” said author and abuse survivor Myriam Gurba, whose 2023 essay collection “Creep: Accusations and Confessions” explores gender violence.

The case threw into stark reality a devastating truth — that domestic violence is uniquely deadly for women and girls. Between a third and half of all female homicide victims in the U.S. are killed by a current or former male partner, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Bureau of Justice Statistics.

That percentage that has held steady for decades, even as the overall number of killings has plunged, from about 23,000 homicides nationwide in 1994 to an estimated 18,000 in 2023.

Few victims and even fewer lawmakers knew those statistics before Simpson‘s arrest. But the case got people talking.

The Need for Action

Giggans was among the millions who watched the Bronco chase on live TV. But unlike most, she was watching with a plan.

“I remember watching it, eating Haagen-Dazs ice cream in my living room in Mar Vista with about six other advocates for domestic violence prevention,” she said. “None of us could get enough of it at the time. But we had an ulterior motive because, for us, it was an educational opportunity. [Suddenly] the media cared what we had to say.”

By then, national news outlets had already uncovered police reports and court records detailing Simpson’s abuse, including a no-contest plea to battery charges stemming from a bloody incident in 1989.

News vans began camping around the block at the Los Angeles Commission on Assaults Against Women’s Hollywood Boulevard headquarters, queuing up for interviews. Overnight, advocates became sought-after stars on TV.

“It was an amazingly consequential period,” Giggans said.

It wasn’t merely that Simpson was a wealthy celebrity, or that he had fled police, or that he was arrested by the same law enforcement agency whose officers had been caught on camera beating Rodney King.

“To a lot of people it was a case about race and mistreatment of Black residents by the LAPD, but to us it was the first time that a huge spotlight was focusing on domestic violence,” said Pincus of the Domestic Abuse Center.

By 1994, California was beginning to enforce 1986 changes to its domestic violence laws, which required police to treat family assaults as they would public ones, and to keep records of calls where no arrests were made.

“If you arrived at a scene and there’s a battery or attempted murder, you can’t just not do anything because it’s ‘a domestic,’” as police had done previously, Pincus said. “The other part of the law change said that every police department in the state had to have mandatory domestic violence training, and those protocols had to be established and made public.”

At the same time, Democrats in Congress were working to pass the landmark Violence Against Women Act, which would

SDGs, Targets, and Indicators in the Article

1. Which SDGs are addressed or connected to the issues highlighted in the article?

- SDG 5: Gender Equality

- SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities

- SDG 16: Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions

2. What specific targets under those SDGs can be identified based on the article’s content?

- SDG 5.2: Eliminate all forms of violence against all women and girls in the public and private spheres, including trafficking and sexual and other types of exploitation.

- SDG 10.2: Empower and promote the social, economic, and political inclusion of all, irrespective of age, sex, disability, race, ethnicity, origin, religion, or economic or other status.

- SDG 16.1: Significantly reduce all forms of violence and related death rates everywhere.

3. Are there any indicators mentioned or implied in the article that can be used to measure progress towards the identified targets?

- Number of domestic violence incidents reported and prosecuted.

- Availability and accessibility of domestic violence programs, shelters, and support services.

- Percentage of domestic violence survivors who have access to emergency shelter, medical care, and legal assistance.

- Percentage of unhoused women who have experienced domestic violence.

Table: SDGs, Targets, and Indicators

| SDGs | Targets | Indicators |

|---|---|---|

| SDG 5: Gender Equality | Target 5.2: Eliminate all forms of violence against all women and girls in the public and private spheres, including trafficking and sexual and other types of exploitation. | – Number of domestic violence incidents reported and prosecuted. – Availability and accessibility of domestic violence programs, shelters, and support services. |

| SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities | Target 10.2: Empower and promote the social, economic, and political inclusion of all, irrespective of age, sex, disability, race, ethnicity, origin, religion, or economic or other status. | – Percentage of domestic violence survivors who have access to emergency shelter, medical care, and legal assistance. – Percentage of unhoused women who have experienced domestic violence. |

| SDG 16: Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions | Target 16.1: Significantly reduce all forms of violence and related death rates everywhere. | – Number of domestic violence incidents reported and prosecuted. – Availability and accessibility of domestic violence programs, shelters, and support services. |

Behold! This splendid article springs forth from the wellspring of knowledge, shaped by a wondrous proprietary AI technology that delved into a vast ocean of data, illuminating the path towards the Sustainable Development Goals. Remember that all rights are reserved by SDG Investors LLC, empowering us to champion progress together.

Source: latimes.com

Join us, as fellow seekers of change, on a transformative journey at https://sdgtalks.ai/welcome, where you can become a member and actively contribute to shaping a brighter future.