Sex Differences in Obstructive Lung Disease – European Medical Journal

Report on Sex and Gender Disparities in Respiratory Health: A Sustainable Development Goals Perspective

Introduction: Aligning Respiratory Health with Global Development Targets

Disparities in lung disease based on sex and gender represent a significant challenge to achieving global health equity. These differences, rooted in biology and shaped by sociocultural factors, impact disease incidence, progression, and therapeutic response across the lifespan. Current clinical paradigms often follow a ‘one-size-fits-all’ model, which is fundamentally at odds with the principles of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Addressing these disparities is crucial for making progress on several Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly:

- SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being: Failing to account for sex-specific pathophysiology hinders efforts to reduce premature mortality from non-communicable diseases (Target 3.4) and deliver effective, equitable healthcare.

- SDG 5: Gender Equality: Overlooking how gender roles influence environmental exposures, health-seeking behaviours, and clinical diagnoses perpetuates systemic inequalities in health outcomes.

- SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities: The gap in respiratory health outcomes between sexes is a clear form of inequality that must be addressed to ensure inclusive social and health systems.

This report analyzes the evidence on sex and gender differences in lung disease, highlighting the need to integrate these variables into research, policy, and clinical practice to advance the global health agenda.

Analysis of Sex-Based Disparities in Lung Disease Across the Lifespan

Developmental Origins and Early Life

The foundations of sex-based respiratory health disparities are established during fetal development. Key differences include:

- Pulmonary Maturation: Female fetuses typically produce pulmonary surfactant earlier than males, a process influenced by estrogens and androgens. This developmental divergence contributes to a significantly higher risk of respiratory distress syndrome in preterm male infants.

- Postnatal Susceptibility: Following birth, male infants exhibit an elevated risk for bronchopulmonary dysplasia, a chronic lung disease linked to premature birth, reflecting sex-based differences in lung injury and repair mechanisms.

Hormonal Transitions and Lifespan Vulnerabilities

Disease patterns shift throughout life, often corresponding with major hormonal changes. Puberty marks a transition where asthma becomes more prevalent and severe in adolescent and adult females. Later in life, menopause serves as another critical inflection point, with many women experiencing an accelerated decline in pulmonary function and an increased risk for new-onset asthma and COPD progression. A life-course approach to health, central to achieving SDG 3, requires understanding and addressing these sex-specific vulnerabilities at each stage.

Key Determinants of Sex Differences in Pulmonary Health

Hormonal and Immunological Mechanisms

Sex hormones, including estrogen, progesterone, and androgens, modulate lung physiology and immune responses. In women, hormonal fluctuations across the menstrual cycle, pregnancy, and menopause directly impact respiratory conditions like asthma. For instance, up to 40% of women with asthma report premenstrual worsening of symptoms. The immune system is also heavily influenced by sex; females generally mount more robust immune responses, which can enhance pathogen clearance but also increases susceptibility to allergic and autoimmune conditions. In contrast, testosterone often has immunosuppressive effects, contributing to different inflammatory pathways in males.

Genetic and Genomic Factors

Advances in genomics reveal a molecular basis for sex-based health differences. Transcriptomic studies have identified thousands of genes with sex-biased expression in lung tissue and distinct inflammatory pathways activated in males and females with asthma. Furthermore, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have uncovered asthma-associated genetic loci with sex-specific effects. Incorporating sex-stratified analyses into all ‘omics’ research is essential for advancing precision medicine and ensuring that diagnostic and therapeutic innovations benefit all populations, a key tenet of SDG 3.

Socio-Environmental Factors and Gender Intersectionality

Gender—the sociocultural roles and norms associated with sex—critically influences exposures, behaviours, and healthcare access, compounding biological vulnerabilities. This intersection is a primary concern for achieving SDG 5 (Gender Equality) and SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities). Key examples include:

- Household Air Pollution: In many low- and middle-income countries, traditional gender roles result in women being disproportionately exposed to biomass smoke from cooking, leading to elevated rates of COPD.

- Occupational Exposures: Gendered employment patterns can lead to differential exposure to industrial dusts, chemicals, and other respiratory hazards.

- Healthcare Access and Bias: Gender can affect health-seeking behaviours and lead to diagnostic bias. Women with COPD, for example, are historically underdiagnosed or misdiagnosed, delaying access to appropriate care and undermining progress towards universal health coverage (Target 3.8).

Implications for Clinical Practice and Public Health Policy

Advancing Towards Personalized Respiratory Care

The evidence of profound sex differences necessitates a move away from uniform treatment strategies. In conditions from asthma to lung cancer, sex-specific factors influence therapeutic response. For example, women are more likely to have EGFR-mutated lung cancer, which responds well to specific targeted therapies. Tailoring treatments based on sex-specific phenotypes, hormonal status, and immune profiles is the next frontier in personalized medicine and is essential for optimizing health outcomes for everyone.

Addressing Gaps in Research and Healthcare Delivery

Significant challenges hinder progress in creating sex- and gender-informed respiratory care. Overcoming these obstacles is critical for building the evidence base needed to achieve SDG 3.

- Lack of Sex-Stratified Data: Many studies are underpowered to detect sex differences or fail to report sex-disaggregated results, limiting the clinical applicability of their findings.

- Exclusion of Hormonal Variables: Data on menstrual status, menopause, and hormonal therapy use are frequently omitted from research, despite their clear relevance.

- Preclinical Model Bias: A historical reliance on male-dominated animal and cellular models has perpetuated a biased understanding of disease pathophysiology.

- Insufficient Funding and Training: There is a need for dedicated funding and formal training to build capacity for sex- and gender-based research.

Conclusion and Recommendations: A Call to Action for Equitable Health Outcomes

Integrating sex and gender as fundamental variables in respiratory health is not merely a scientific imperative but a requirement for achieving global health equity as outlined in the Sustainable Development Goals. Decades of sex-agnostic research have created knowledge gaps that perpetuate health inequalities. To build a more equitable and effective framework for preventing and treating lung disease, a concerted effort is needed.

Recommendations

- Systematic Integration in Research: Mandate the inclusion of sex and gender variables in study design, analysis, and reporting across all publicly funded research.

- Dedicated Funding and Collaboration: Establish dedicated funding mechanisms to support sex- and gender-aware studies and foster interdisciplinary collaboration between pulmonology, endocrinology, immunology, and social sciences, in line with the partnership principles of SDG 17.

- Update Clinical Guidelines: Develop and implement sex- and gender-informed clinical guidelines to improve diagnostic accuracy and therapeutic efficacy.

- Promote Inclusive Research: Ensure the intentional recruitment of underrepresented populations, including transgender individuals, in clinical cohorts to ensure that medical advancements leave no one behind.

Analysis of Sustainable Development Goals in the Article

1. Which SDGs are addressed or connected to the issues highlighted in the article?

- SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being: This is the most central SDG addressed. The article extensively discusses various lung diseases such as asthma, COPD, lung cancer, and respiratory distress syndrome in infants. It focuses on disease incidence, severity, progression, and treatment responses, all of which are core components of ensuring healthy lives and promoting well-being for all ages. It also touches upon maternal and infant health, noting the higher risk of respiratory distress in preterm male infants and the impact of uncontrolled asthma during pregnancy.

- SDG 5: Gender Equality: The article’s primary thesis is built around the disparities in lung health based on both biological sex and sociocultural gender. It argues against “male-dominated studies” and “sex-agnostic trial designs,” calling for research and clinical practices that acknowledge and address the unique health needs of females. It highlights how gender roles lead to different environmental exposures (e.g., biomass smoke for women) and diagnostic biases, directly linking to the goal of achieving gender equality and empowering all women and girls.

- SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities: The article details significant health inequalities between males and females across their lifespan. For example, it states that preterm male infants are “nearly twice as likely to develop” respiratory distress syndrome, while asthma becomes “more prevalent and severe in adolescent and adult females.” By advocating for sex-informed research and personalized medicine, the article aims to reduce these inequalities in health outcomes.

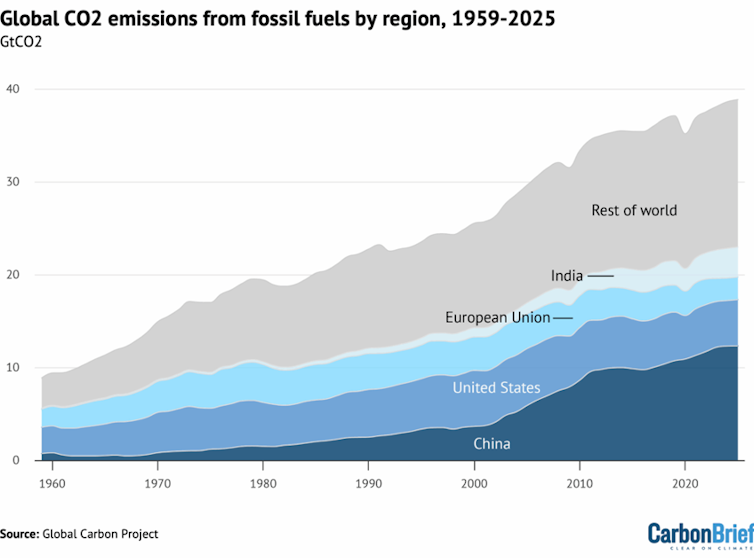

- SDG 7: Affordable and Clean Energy: The article connects lung disease to energy sources by mentioning that in “low- and middle-income countries… women are disproportionately exposed to biomass smoke due to traditional cooking practices, resulting in elevated rates of COPD.” This directly relates to the need for access to clean and modern energy for cooking to prevent household air pollution.

- SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities: The text identifies “air pollution” as an environmental factor that can “impair fetal lung development” and influence lung function decline with ageing. This connects to the goal of reducing the adverse environmental impact of cities, particularly concerning air quality.

2. What specific targets under those SDGs can be identified based on the article’s content?

- Target 3.4: By 2030, reduce by one third premature mortality from non-communicable diseases through prevention and treatment and promote mental health and well-being. The article’s focus on understanding and better treating chronic lung diseases like asthma, COPD, and lung cancer directly supports this target. It also notes that “women have higher rates of anxiety and depression, conditions that are known to worsen asthma control and COPD outcomes,” linking to the mental health aspect of this target.

- Target 3.2: By 2030, end preventable deaths of newborns and children under 5 years of age. The article’s discussion of the “markedly higher risk of respiratory distress syndrome among preterm male infants” is directly relevant to this target, as understanding the sex-based mechanisms could lead to better prevention and treatment strategies for this neonatal condition.

- Target 3.9: By 2030, substantially reduce the number of deaths and illnesses from hazardous chemicals and air, water and soil pollution and contamination. The article explicitly mentions “air pollution” and “biomass smoke” as environmental exposures that contribute to lung disease, aligning with the goal of reducing illness from air pollution.

- Target 5.c: Adopt and strengthen sound policies and enforceable legislation for the promotion of gender equality and the empowerment of all women and girls at all levels. The article supports this by highlighting positive policy changes, stating that “Federal funding policies, along with updated journal editorial standards, are promoting more equitable research practices” that mandate the inclusion of sex as a biological variable.

- Target 10.3: Ensure equal opportunity and reduce inequalities of outcome. The entire article is a call to reduce inequalities in health outcomes between sexes. It points out issues like women being “historically underdiagnosed or misdiagnosed” with COPD and the failure of clinical trials to “analyse or report outcomes by sex,” which perpetuates these inequalities.

- Target 7.1: By 2030, ensure universal access to affordable, reliable and modern energy services. The link made between high rates of COPD in women in low- and middle-income countries and their exposure to “biomass smoke due to traditional cooking practices” underscores the health imperative behind achieving this energy access target.

3. Are there any indicators mentioned or implied in the article that can be used to measure progress towards the identified targets?

- Disease incidence and prevalence rates, stratified by sex and age: The article provides several examples that could serve as indicators. For instance, tracking the prevalence of asthma in adolescent and adult females versus males, or the incidence of respiratory distress syndrome in preterm male versus female infants. The text notes preterm males are “nearly twice as likely to develop the condition.”

- Proportion of clinical trials and research studies that report sex-disaggregated data: The article implicitly suggests this as a key indicator of progress by criticizing that “most clinical trials fail to analyse or report outcomes by sex” and that researchers “often fail to analyse or report sex-disaggregated results.” Measuring the percentage of studies that do this would track progress towards more equitable research.

- Rates of diagnosis for specific diseases, stratified by gender: To measure and address diagnostic bias, one could use the rate at which COPD is diagnosed in women versus men. The article implies this is a problem area by stating women with COPD are “historically underdiagnosed or misdiagnosed.”

- Morbidity and mortality rates from household air pollution, stratified by gender: The article points to “elevated rates of COPD” in women exposed to biomass smoke. Tracking these rates would be a direct indicator for targets related to clean energy (7.1) and pollution-related illness (3.9).

- Treatment efficacy rates, stratified by sex: The article suggests that responses to therapies for asthma, COPD, and lung cancer differ by sex. For example, it notes women are more likely to have “*EGFR* mutations, which respond well to targeted tyrosine kinase inhibitors.” Tracking treatment outcomes separately for males and females would be a crucial indicator for personalized medicine and reducing health inequalities.

4. Table of SDGs, Targets, and Indicators

| SDGs | Targets | Indicators |

|---|---|---|

| SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being |

3.4: Reduce premature mortality from non-communicable diseases (NCDs).

3.2: End preventable deaths of newborns. |

– Prevalence, severity, and treatment response rates for NCDs (asthma, COPD, lung cancer) stratified by sex and age. – Incidence rate of respiratory distress syndrome in preterm infants, stratified by sex. |

| SDG 5: Gender Equality | 5.c: Adopt and strengthen policies for the promotion of gender equality. |

– Proportion of publicly funded medical research and clinical trials that include and report sex-disaggregated data. – Number of clinical guidelines updated to include sex-specific diagnostic criteria and treatment recommendations. |

| SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities | 10.3: Ensure equal opportunity and reduce inequalities of outcome. |

– Rates of diagnosis and misdiagnosis for diseases like COPD, stratified by gender. – Data on treatment efficacy and adverse event rates for respiratory medications, stratified by sex. |

| SDG 7: Affordable and Clean Energy | 7.1: Ensure universal access to affordable, reliable and modern energy services. | – Incidence and prevalence of COPD among women in low- and middle-income countries, correlated with exposure to biomass smoke from traditional cooking practices. |

| SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities | 11.6: Reduce the adverse per capita environmental impact of cities, including by paying special attention to air quality. | – Data on lung function decline and new-onset asthma correlated with exposure to ambient air pollution, stratified by sex. |

Source: emjreviews.com

What is Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0