Boston launches mobile lab to track air pollution block by block – WCVB

Initiative Overview: Boston’s Air Quality Monitoring Program

The City of Boston has initiated a strategic partnership with researchers from Northeastern University to deploy a mobile air pollution laboratory. This initiative is designed to generate high-resolution, block-by-block air quality data, with an initial focus on the Allston-Brighton neighborhood to assess traffic emissions from the Massachusetts Turnpike. This collaboration exemplifies a multi-stakeholder approach, central to Sustainable Development Goal 17 (Partnerships for the Goals), by uniting municipal government, academia, and community organizations to address urban environmental challenges.

Strategic Objectives and Alignment with Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

The program’s objectives are directly aligned with several key SDGs, aiming to create a healthier and more sustainable urban environment.

- Enhance Urban Health and Well-being (SDG 3): By providing residents with precise, color-coded pollution maps, the initiative empowers them to make informed decisions about outdoor activities, thereby reducing exposure to harmful pollutants and mitigating negative health impacts.

- Build Sustainable Cities and Communities (SDG 11): The project directly addresses Target 11.6, which calls for reducing the adverse per capita environmental impact of cities by improving air quality. The granular data collected will enable targeted interventions to create a more resilient and sustainable urban community.

- Promote Climate Action (SDG 13): While monitoring local pollutants, the program acknowledges and aims to mitigate the health impacts of climate-related challenges, such as increased air pollution from wildfires and high-temperature days.

Methodology and Implementation

Mobile Laboratory Deployment

A mobile laboratory van is tasked with measuring U.S. EPA-regulated “criteria pollutants.” The data collected will be used to generate a detailed pollution map where pollutant concentrations are color-coded, allowing for easy identification of air quality hot spots. The van is currently operational, with one reading detecting ozone levels at 32 parts per billion (ppb), compared to the 70 ppb threshold for a poor air quality designation. Formal data collection is scheduled to commence on October 1.

Community-Based Sensor Network and Grants

To further this goal, the city has allocated $1.1 million in Community Clean Air Grants to six local non-profits. A key recipient, the Allston-Brighton Health Collaborative, is partnering with Northeastern University on a project that contributes to SDG 3 and SDG 11 through a two-phase implementation plan:

- Installation of approximately 30 air quality sensors in both indoor and outdoor residential settings throughout Allston-Brighton.

- A subsequent testing phase to evaluate the effectiveness of in-home air purifiers in improving indoor air quality and, consequently, resident health.

Context and Future Outlook

While Boston’s overall air quality is considered favorable for a major city, officials recognize emerging environmental threats that necessitate proactive monitoring and mitigation. This initiative is a response to new challenges that impact urban air quality and public health.

Emerging Environmental Challenges

- Increased frequency and intensity of wildfires leading to smoke and particulate matter influx.

- Adverse air quality conditions associated with high-temperature “heat dome” events.

By addressing these issues through targeted data collection and community-led interventions, the City of Boston reinforces its commitment to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals, ensuring a healthier, more resilient, and sustainable future for its residents.

Analysis of SDGs, Targets, and Indicators

1. Which SDGs are addressed or connected to the issues highlighted in the article?

-

SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being

The article directly connects air quality to public health. The initiative’s primary goal is to make residents healthier by providing them with data on air pollution. The text states, “we also know that air quality really does health impacts,” and the overall aim of the funded projects is “making Boston and its residents healthier.”

-

SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities

The project is a city-led initiative focused on improving the urban environment. By deploying a mobile lab to “map air pollution with block-by-block precision” in a Boston neighborhood, the city is actively working to monitor and manage its environmental quality, making it a more sustainable and healthier place to live.

-

SDG 13: Climate Action

The article links poor air quality to climate-related challenges. It mentions “new challenges like wildfires, like hot days” as contributors to bad air quality. The city’s effort to “mitigate those impacts” demonstrates a focus on building resilience and adapting to the effects of climate change.

-

SDG 17: Partnerships for the Goals

The entire initiative is built on collaboration. The article highlights a partnership between the city of Boston, an academic institution (Northeastern University), and a non-profit organization (Allston-Brighton Health Collaborative). This multi-stakeholder approach is central to achieving the goals outlined.

2. What specific targets under those SDGs can be identified based on the article’s content?

-

Target 3.9: Reduce deaths and illnesses from pollution

By 2030, substantially reduce the number of deaths and illnesses from hazardous chemicals and air, water and soil pollution and contamination. The project directly addresses this by measuring air pollutants and empowering residents to avoid exposure, with the long-term goal of reducing health problems associated with poor air quality.

-

Target 11.6: Reduce the environmental impact of cities

By 2030, reduce the adverse per capita environmental impact of cities, including by paying special attention to air quality. The project’s core function is to measure and map air pollution from sources like “traffic emissions from the Massachusetts Turnpike,” which is a direct action towards monitoring and managing the city’s air quality.

-

Target 13.1: Strengthen resilience to climate-related disasters

Strengthen resilience and adaptive capacity to climate-related hazards and natural disasters in all countries. The article mentions the city’s need to address air quality issues arising from “wildfires” and “hot days,” which are climate-related hazards. The monitoring program is a tool to build resilience and inform mitigation strategies.

-

Target 17.17: Encourage effective partnerships

Encourage and promote effective public, public-private and civil society partnerships. The project is a clear example of this target in action, described as “Boston is partnering with Northeastern University researchers” and the “Allston-Brighton Health Collaborative, partnering with Northeastern” receiving a grant from the city.

3. Are there any indicators mentioned or implied in the article that can be used to measure progress towards the identified targets?

-

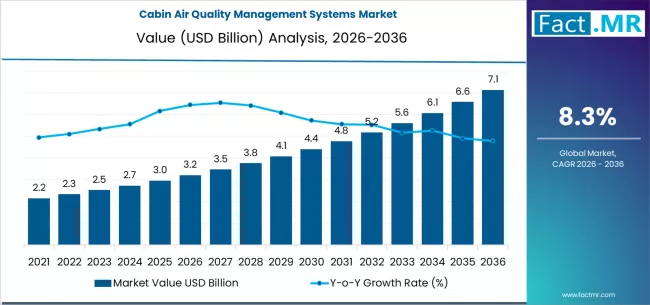

Indicator for Target 11.6 (Indicator 11.6.2)

The article explicitly mentions the measurement of specific air pollutants. The statement, “The van is currently detecting 32 parts per billion of ozone, with 70 parts per billion indicating a bad air quality day,” is a direct example of collecting data for the indicator ‘Annual mean levels of fine particulate matter (e.g. PM2.5 and PM10) in cities.’ Although ozone is mentioned instead of PM2.5, it is a key “criteria pollutant” used to measure urban air quality.

-

Implied Indicator for Target 3.9 (Indicator 3.9.1)

While the article does not mention mortality rates, the entire project is designed to reduce exposure to ambient air pollution. The data collected on pollution hotspots and the testing of air purifiers are actions aimed at mitigating the root cause measured by ‘Mortality rate attributed to household and ambient air pollution.’

-

Qualitative Indicators for Targets 13.1 and 17.17

The article provides qualitative evidence of progress. For Target 13.1, the city’s stated intention to “really think about how we’re mitigating those impacts” of wildfires and heat serves as an indicator of developing adaptive strategies. For Target 17.17, the existence of the funded partnership itself, with “$1.1 million in Community Clean Air Grants” awarded by the city to nonprofits and academic partners, is a direct indicator of a functioning multi-stakeholder partnership.

4. Summary Table of SDGs, Targets, and Indicators

| SDGs | Targets | Indicators Identified in Article |

|---|---|---|

| SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being | Target 3.9: By 2030, substantially reduce the number of deaths and illnesses from hazardous chemicals and air, water and soil pollution and contamination. | Implied Indicator (related to 3.9.1): Efforts to reduce exposure to ambient air pollution through localized monitoring and installation of air purifiers. |

| SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities | Target 11.6: By 2030, reduce the adverse per capita environmental impact of cities, including by paying special attention to air quality. | Direct Indicator (related to 11.6.2): Measurement of specific air pollutants, such as detecting ozone levels in parts per billion (ppb). |

| SDG 13: Climate Action | Target 13.1: Strengthen resilience and adaptive capacity to climate-related hazards and natural disasters in all countries. | Qualitative Indicator: The city’s stated goal to mitigate the air quality impacts of climate-related challenges like “wildfires” and “hot days.” |

| SDG 17: Partnerships for the Goals | Target 17.17: Encourage and promote effective public, public-private and civil society partnerships. | Qualitative Indicator: The formation of a multi-stakeholder partnership between the city, a university, and a nonprofit, funded by city grants. |

Source: wcvb.com

What is Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0