Bergman urges delisting of the gray wolf from endangered species list – thealpenanews.com

Report on the Proposed Delisting of the Gray Wolf from the Endangered Species Act

A coalition of United States House Members, led by Representative Jack Bergman, has formally requested that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) delist the gray wolf from the Endangered Species Act (ESA). The request urges a return of management authority to state and tribal bodies, citing the successful recovery of the species and advocating for policy decisions grounded in scientific data rather than political or judicial influence. This initiative directly engages with several key United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly those concerning biodiversity, institutional governance, and collaborative partnerships.

Analysis of Key Arguments and SDG Alignment

The central arguments for delisting the gray wolf are intrinsically linked to the principles of sustainable development, balancing ecological health with socio-economic realities and effective governance.

SDG 15: Life on Land

This goal, which aims to protect, restore, and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, is at the core of the debate. The call for delisting is predicated on the assertion that conservation efforts have been successful, aligning with targets for protecting threatened species.

- Species Recovery: Proponents argue that gray wolf populations have surpassed all recovery goals, transitioning from a species in need of federal protection to one that can be managed sustainably at the state and tribal level.

- Human-Wildlife Coexistence: Continued federal listing is said to ignore the challenges faced by rural communities. Returning management to local authorities is presented as a necessary step to implement strategies that reduce human-wildlife conflict, a critical component of sustainably managing ecosystems where human and animal populations interact.

- Sustainable Management: The request emphasizes that state and tribal wildlife programs are capable of maintaining healthy wolf populations through proven tools, ensuring the long-term viability of the species while addressing local concerns.

SDG 16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions

The conflict over the gray wolf’s status highlights challenges in governance and the interpretation of environmental law, reflecting the importance of effective and accountable institutions.

- Institutional Conflict: The issue is characterized by a divergence between the FWS’s scientific assessments, Congressional intent behind the ESA, and recent federal court rulings. Lawmakers contend that judicial overreach has imposed new delisting standards not present in the original legislation.

- Science-Based Policymaking: A primary appeal is for the FWS to rely on scientific data demonstrating stable and self-sustaining wolf populations, rather than judicial interpretations that, it is argued, misapply the law. This aligns with the goal of building effective institutions that operate on evidence-based principles.

- Jurisdictional Clarity: The report advocates for restoring the intended function of the ESA as a tool for species recovery, not perpetual federal control. It calls for clear jurisdictional authority, returning management to local institutions once federal recovery objectives have been met.

SDG 17: Partnerships for the Goals

The history of the gray wolf’s recovery and the proposed path forward underscore the value of multi-stakeholder collaboration.

- Collaborative Success: The letter acknowledges that the wolf’s recovery was achieved through the “collaborative work among states, tribes, conservation groups, private landowners, and federal partners.”

- Empowering Local Partners: The call to return management authority to states and tribes is framed as empowering the local partners who are most familiar with on-the-ground conditions and best positioned to manage the species sustainably.

Chronology of Regulatory and Judicial Actions

The current debate is shaped by a series of conflicting administrative rules and court decisions.

- November 2020: The FWS published a final rule to delist the gray wolf across the lower 48 states, concluding that the species was recovered and no longer met the ESA’s definition of threatened or endangered.

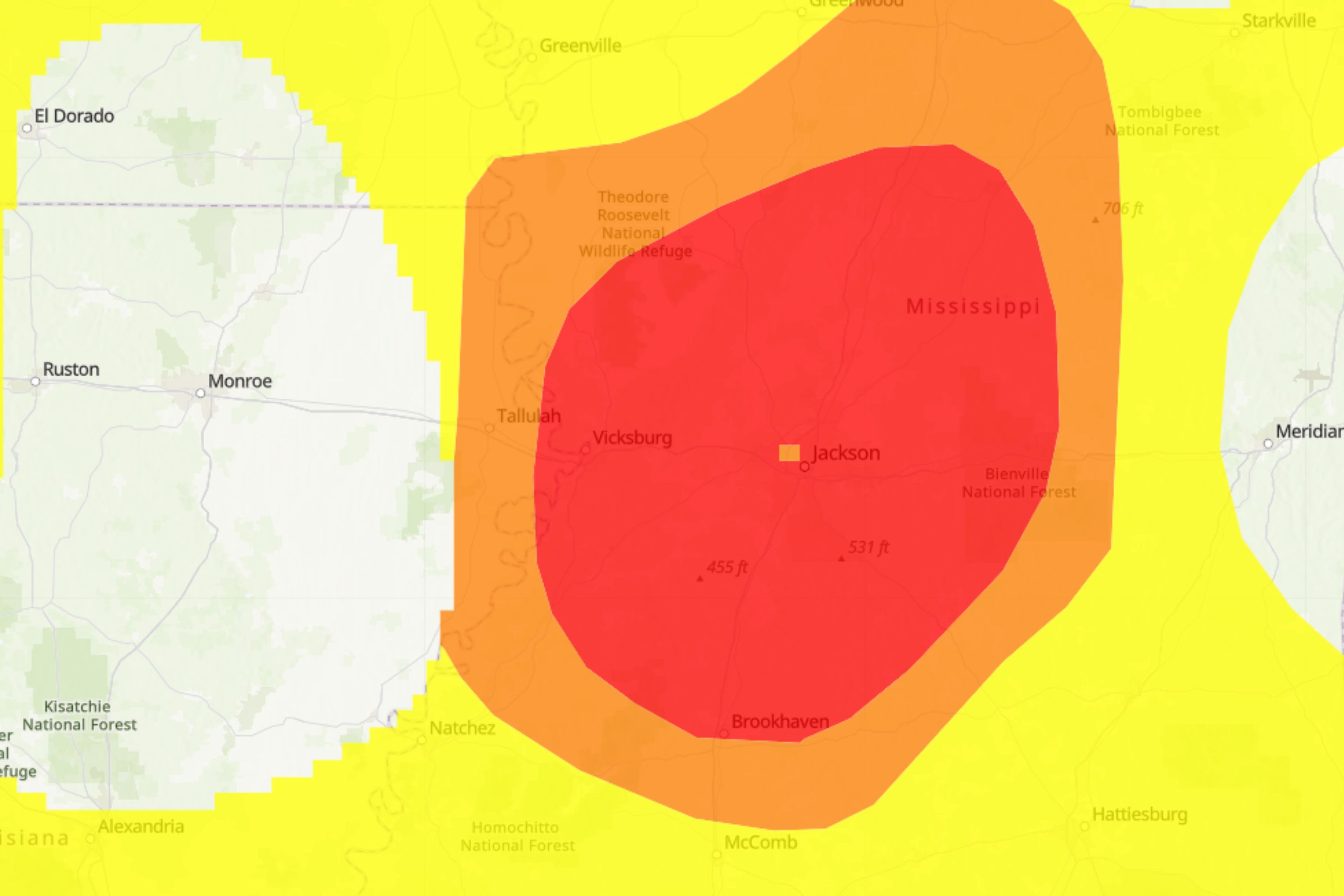

- February 2022: The U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California vacated the 2020 rule, reinstating federal protections. The court argued the FWS failed to consider the wolf’s absence from its historical range.

- February 2024: In response to new petitions, the FWS found that other wolf populations did not warrant listing under the ESA.

- Subsequent Rulings: Further court decisions have reinforced the “historic range” standard, which the FWS and proponents of delisting argue is an incorrect interpretation of the ESA’s requirement that a species be in danger of extinction in “all or a significant portion of its range.”

Conclusion and Recommendations

The coalition of House Members urges the FWS to take decisive action to resolve the ongoing conflict and align federal policy with what they assert is both scientific consensus and the original intent of the ESA. The primary recommendation is for the FWS to reissue its 2020 rule delisting the gray wolf.

This action would reaffirm the success of collaborative conservation efforts and empower state and tribal authorities to implement management plans. Such a move would support the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals by promoting effective institutional governance (SDG 16), fostering local partnerships (SDG 17), and ensuring the long-term, sustainable management of a recovered species within its ecosystem (SDG 15).

Analysis of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in the Article

1. Which SDGs are addressed or connected to the issues highlighted in the article?

-

SDG 15: Life on Land

This goal is central to the article, which focuses on the conservation and management of a terrestrial species, the gray wolf. It discusses issues of species recovery, protection of threatened species, biodiversity, and human-wildlife conflict, all of which are core components of SDG 15.

-

SDG 16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions

The article highlights a significant conflict between different branches of government (judicial and executive) and levels of government (federal, state, and tribal). The debate over the interpretation of the Endangered Species Act (ESA), judicial rulings overriding agency decisions, and the call for returning management authority to local entities all relate to the effectiveness, accountability, and inclusivity of institutions, which is the focus of SDG 16.

-

SDG 17: Partnerships for the Goals

The article explicitly mentions that the successful recovery of the gray wolf was a result of “collaborative work among states, tribes, conservation groups, private landowners, and federal partners.” This directly points to the importance of multi-stakeholder partnerships in achieving conservation and sustainable development objectives, a key principle of SDG 17.

2. What specific targets under those SDGs can be identified based on the article’s content?

-

Under SDG 15: Life on Land

- Target 15.5: “Take urgent and significant action to reduce the degradation of natural habitats, halt the loss of biodiversity and, by 2020, protect and prevent the extinction of threatened species.” The entire article is a debate about the status of a formerly threatened species. The argument that the gray wolf has “recovered far beyond the levels that originally warranted their listing” directly relates to the goal of preventing extinction and managing recovered populations.

- Target 15.7: “Take urgent action to end poaching and trafficking of protected species…” While not about illegal poaching, the discussion of implementing “regulated hunting seasons” as a management tool by states and tribes touches upon the principles of managing protected or formerly protected wildlife populations.

- Target 15.9: “…integrate ecosystem and biodiversity values into national and local planning…” The call to “return management authority to states and tribes” and allow them to develop strategies that “balance conservation goals with the needs of local communities” is a direct appeal for integrating biodiversity management into local planning to address issues like human-wildlife conflict.

-

Under SDG 16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions

- Target 16.6: “Develop effective, accountable and transparent institutions at all levels.” The conflict between FWS rules and federal court decisions, and the plea to “rely on science – not politics,” points to a challenge in institutional effectiveness and accountability in wildlife management.

- Target 16.7: “Ensure responsive, inclusive, participatory and representative decision-making at all levels.” The core argument of the letter is to return management to “states and local tribes” and “the people who live with these animals every day,” which is a call for a more inclusive and responsive decision-making process that involves local stakeholders.

-

Under SDG 17: Partnerships for the Goals

- Target 17.17: “Encourage and promote effective public, public-private and civil society partnerships…” The article explicitly credits the wolf’s recovery to the “collaborative work among states, tribes, conservation groups, private landowners, and federal partners,” showcasing a successful multi-stakeholder partnership.

3. Are there any indicators mentioned or implied in the article that can be used to measure progress towards the identified targets?

- Population Status of Species: The article repeatedly refers to the gray wolf population having “surpassed recovery goals” and being “stable, self-sustaining, and thriving.” The official listing status of a species under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) serves as a direct indicator of its conservation status.

- Geographic Range of Species: A key point of contention discussed is whether a species must “repopulate its entire historic range” to be delisted. The extent of a species’ current range versus its historic range is used as a metric in the legal and scientific debate.

- Level of Management Authority: The primary request in the article is to “return management authority to states and local tribes.” The level of governance (federal vs. state/tribal) responsible for wildlife management is an implied indicator of progress towards more localized and participatory decision-making (Target 16.7).

- Incidence of Human-Wildlife Conflict: The article mentions that state and tribal management includes tools that “help reduce human-wildlife conflict.” The frequency and severity of such conflicts can be used as an indicator to measure the effectiveness of local management plans.

- Existence of State and Tribal Management Plans: The letter advocates for the authority of “state and tribal wildlife management programs,” implying that the existence and implementation of these plans are indicators of local capacity to manage wildlife sustainably.

4. Table of SDGs, Targets, and Indicators

| SDGs | Targets | Indicators (Mentioned or Implied in the Article) |

|---|---|---|

| SDG 15: Life on Land |

15.5: Protect and prevent the extinction of threatened species.

15.9: Integrate ecosystem and biodiversity values into local planning. |

– Official status of the gray wolf on the Endangered Species Act (ESA) list (listed vs. delisted). – Population numbers and stability (“stable, self-sustaining, and thriving”). – Geographic range of the species (current vs. historic). – Incidents of human-wildlife conflict. – Existence and implementation of state/tribal management plans. |

| SDG 16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions |

16.6: Develop effective, accountable and transparent institutions.

16.7: Ensure responsive, inclusive, and participatory decision-making. |

– Number of conflicting rules and court orders regarding species management. – Level of management authority devolved from federal to state and tribal governments. – Use of “sound science” as the basis for agency decisions. |

| SDG 17: Partnerships for the Goals | 17.17: Encourage and promote effective public, public-private and civil society partnerships. | – Number and type of stakeholders involved in conservation efforts (states, tribes, conservation groups, private landowners, federal partners). |

Source: thealpenanews.com

What is Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0