Is there such a thing as a psychopath? with Rasmus Rosenberg Larsen – University of Chicago News

Report on the Use of Psychopathy Assessments in Legal Systems and its Conflict with Sustainable Development Goals

Executive Summary

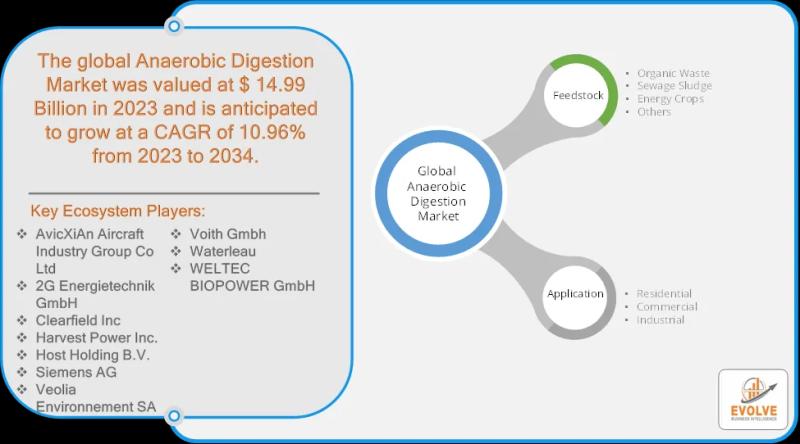

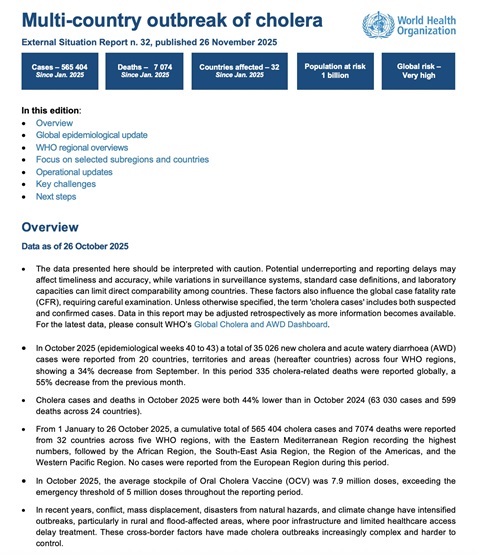

An analysis of the clinical construct of “psychopathy” reveals a significant disconnect between its application in forensic settings and the empirical evidence base. The continued use of assessment tools like the Hare Psychopathy Checklist-Revised (PCLR) within legal systems directly undermines key principles of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 16 (Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions), SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being), and SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities). This report outlines the historical context, scientific failings, and detrimental consequences of this practice, concluding with a call for a moratorium to realign legal and clinical practices with global standards for justice, health, and equality.

Historical Development and Institutional Integration

Origins of the Concept

The concept of a moral disorder dates back to the 18th century, first scientifically iterated by Benjamin Rush in 1786. It described an inability to distinguish between moral right and wrong. For centuries, the idea remained on the fringes of clinical and behavioral science, often dismissed as a “wastebasket diagnosis.”

The Turning Point in the 1990s

The 1990s marked a significant shift, driven by socio-political factors rather than scientific breakthroughs. This integration into the justice system was influenced by:

- The “Get-Tough-on-Crime” Movement: A legal and political demand arose for tools to identify “super predators” or prolific, problematic individuals, creating an opportunity for concepts like psychopathy to gain traction.

- Cultural Fascination: A rise in media portrayals of psychopaths, amplified by events like the televised trial of Ted Bundy, created public and institutional familiarity with the term.

- Standardization of Tools: The development and revision of the Hare Psychopathy Checklist (PCLR) provided a standardized instrument that researchers and clinicians rallied behind, creating a cohesive but ultimately flawed research paradigm.

This integration represents a failure in institutional accountability (SDG 16.6), as a scientifically questionable tool was adopted to inform high-stakes legal decisions without sufficient critical oversight.

Scientific Scrutiny of Core Claims

The use of psychopathy assessments in legal contexts is predicated on five central evidence-based claims, all of which have been systematically challenged or refuted by subsequent meta-analyses and systematic reviews over the past two decades.

Five Debunked Assertions

- Extraordinary Dangerousness: The claim that individuals with high PCLR scores are the “worst of the worst” is not supported by data. Recidivism rates between high-scoring and lower-scoring groups show a statistically insignificant difference, making the label a poor predictor of future risk.

- Untreatability: The assertion that these individuals are incorrigible and cannot benefit from rehabilitation is false. Evidence indicates they benefit from treatment programs at rates comparable to other justice-involved individuals. This false claim directly obstructs pathways to rehabilitation, undermining both individual well-being (SDG 3) and the justice system’s restorative goals (SDG 16).

- Moral-Psychological Deficit: The idea of a unique moral incapacity, such as a lack of empathy, is not substantiated. Controlled studies on moral psychology and empathy consistently yield null findings, showing no significant difference between groups.

- Biological Foundation: Despite over a hundred neurological studies, primarily using MRI technology, no consistent brain-based marker for psychopathy has been identified. Early theories about deficits in the amygdala have not been supported by systematic reviews.

- A Well-Understood Construct: The claim that psychopathy is a well-understood, measurable phenomenon is incorrect. The PCLR is not a valid measure of a discrete underlying condition; it is a tool that selects individuals based on a collection of traits, without evidence of a unique pathology.

Impact on Justice, Equality, and Well-being

Undermining SDG 16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions

The application of the psychopathy label has severe, almost exclusively negative, consequences that corrupt the principles of fair and evidence-based justice. Labeling an individual with psychopathy leads to a dramatic increase in restrictive and punitive decisions, thereby compromising the goal of providing access to justice for all (SDG 16.3).

- Sentencing and Incarceration: It is used as aggravating information, increasing the likelihood of a prison sentence over a community sentence and influencing correctional placement in high-risk institutions.

- Parole and Rehabilitation: The label heavily influences decision-makers, such as judges and parole boards, who often interpret it as evidence that an individual cannot change. This directly limits access to rehabilitation and opportunities for parole, creating a biased and unjust system.

- Prevalence: Estimates suggest hundreds of thousands of individuals in the North American legal system have been assessed with the PCLR, indicating a widespread systemic issue that requires urgent institutional reform.

Violating SDG 3 (Good Health) and SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities)

The use of psychopathy assessments is ethically problematic and exacerbates societal inequalities.

- Ethical Harm: Clinicians are bound by the principle to “do no harm.” Administering an assessment that offers no benefit to the individual and is almost certain to result in negative legal consequences is a violation of this professional ethic, directly impacting the individual’s mental and overall well-being (SDG 3).

- Perpetuating Inequality: The individuals subjected to these assessments are often from marginalized communities with limited resources. By applying a misleading and stigmatizing label, the system perpetuates a cycle of disadvantage and limits opportunities for successful reintegration into society, thus deepening inequalities of outcome (SDG 10.3).

Conclusion and Recommendations for SDG Alignment

A Call for a Moratorium

The concept of psychopathy, as applied in forensic settings, functions as a “zombie idea”—a scientifically defunct theory that continues to inflict harm. Its persistence is due to institutional inertia and the influence of a small number of expert witnesses repeating outdated claims.

To align the justice system with the Sustainable Development Goals, a moratorium on the clinical and legal use of psychopathy assessments is necessary. This action is critical for:

- Strengthening Institutions (SDG 16): Ceasing the use of the PCLR would eliminate a significant source of bias and misinformation in legal decision-making. Resources should be redirected to validated, mainstream risk assessment tools that offer superior predictive accuracy and do not carry the same prejudicial weight.

- Promoting Health and Reducing Inequality (SDG 3 & 10): A moratorium would protect vulnerable individuals from the harm caused by a stigmatizing and scientifically unsupported label, ensuring that assessments serve a genuine therapeutic or rehabilitative purpose and promoting a more equitable justice system.

The continued use of psychopathy assessments is an indefensible practice that stands in direct opposition to the global commitment to building just, inclusive, and healthy societies.

Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Addressed in the Article

The article discusses issues related to mental health, the criminal justice system, scientific integrity, and human rights, which connect to several Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The primary SDGs addressed are:

- SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being: The article centers on a mental health construct, psychopathy, and the profound negative impact of its misdiagnosis and misapplication on the well-being of individuals within the legal system.

- SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities: The article highlights how the label of “psychopath,” derived from flawed assessments, creates a distinct class of individuals who face systemic discrimination and unequal outcomes within the justice system.

- SDG 16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions: The core of the article is a critique of the criminal justice system’s reliance on a scientifically questionable tool. This raises fundamental questions about fairness, accountability, equal access to justice, and the effectiveness of legal institutions.

Specific SDG Targets Identified

Based on the article’s content, several specific targets under the identified SDGs are relevant:

SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being

- Target 3.4: “By 2030, reduce by one third premature mortality from non-communicable diseases through prevention and treatment and promote mental health and well-being.”

The article directly addresses this target by discussing how the misuse of a mental health diagnosis (psychopathy) causes significant harm. The author states that the assessment “can only really harm the person” and has “exclusively negative consequences,” which is contrary to the goal of promoting mental health and well-being. The call for a moratorium on these assessments is a direct attempt to prevent this harm.

SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities

- Target 10.3: “Ensure equal opportunity and reduce inequalities of outcome, including by eliminating discriminatory laws, policies and practices and promoting appropriate legislation, policies and action in this regard.”

The article argues that using the Psychopathy Checklist-Revised (PCLR) is a discriminatory practice that leads to severe inequalities of outcome. The author notes a “dramatic increase in the probability of having extra restrictive and constructive decisions made about that person,” including harsher sentencing, denial of parole, and placement in high-risk institutions. The call to stop using these assessments is a call to eliminate this discriminatory practice.

SDG 16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions

- Target 16.3: “Promote the rule of law at the national and international levels and ensure equal access to justice for all.”

The article demonstrates how the PCLR assessment undermines equal access to justice. The label of “psychopath” is shown to have a “very heavy weight” on the decision-making of judges and parole boards, biasing them against the individual. This creates a system where justice is not applied equally, as decisions are based on a misleading and prejudicial label rather than objective facts about the individual’s capacity for change or rehabilitation. - Target 16.6: “Develop effective, accountable and transparent institutions at all levels.”

The article critiques the lack of accountability and self-correction within both the scientific community and the legal system. It points out that despite two decades of research showing the flaws in the claims about psychopathy, “the earlier studies are still getting referenced” and experts “still go into court today and say exactly the same thing, as if the research hasn’t changed.” This highlights a failure of these institutions to be effective and accountable to current evidence.

Indicators for Measuring Progress

While the article does not mention official SDG indicators, it provides information that can be used to formulate relevant metrics for measuring progress towards the identified targets.

SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being

- Implied Indicator: Prevalence of use of scientifically unsupported diagnostic tools in forensic mental health assessments.

The article provides data points for this indicator, stating that the PCLR is “among the most utilized tools” and that its use has seen a “tenfold explosion” since the early 2000s, affecting “hundreds of thousands of individuals” in North America. A reduction in the use of such tools would indicate progress.

SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities

- Implied Indicator: Number of legal systems with policies that permit or rely on psychopathy assessments for sentencing, parole, and correctional placement decisions.

The article describes how these assessments are “ingested into the legal system to inform decision-making” across a wide range of areas, including “prison sentence over community sentence,” “capital punishment,” and “parole probation.” Tracking the number of jurisdictions that formally cease this practice would measure progress.

SDG 16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions

- Implied Indicator: Proportion of legal decisions (e.g., sentencing, parole) that are influenced by psychopathy assessments versus evidence-based risk assessment tools.

The author highlights that the information from the PCLR is “misleading you in your decision-making” and that “we have much better tools” for risk assessment. Measuring the shift from the PCLR to more reliable and less prejudicial tools would indicate a move towards a more just and effective system. - Implied Indicator: Rate at which legal and clinical guidelines are updated to reflect current scientific consensus.

The article points to a significant lag, where scientific understanding has advanced but practice has not. The author notes the “odd tension there is between what’s being claimed and the empirical evidence.” An indicator could measure the time it takes for major systematic reviews and meta-analyses to be reflected in the guidelines used by expert witnesses and legal decision-makers.

Table of SDGs, Targets, and Indicators

| SDGs | Targets | Indicators (Identified or Implied in the Article) |

|---|---|---|

| SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being | Target 3.4: Promote mental health and well-being. | Prevalence of use of scientifically invalidated diagnostic tools in forensic settings. The article notes the PCLR is one of the “most utilized tools” and its use has exploded, affecting “hundreds of thousands of individuals.” |

| SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities | Target 10.3: Ensure equal opportunity and reduce inequalities of outcome by eliminating discriminatory practices. | Existence of policies and practices that lead to differential outcomes based on a psychopathy diagnosis. The article cites “aggravating information during sentencing,” denial of parole, and impact on “capital punishment” as unequal outcomes. |

| SDG 16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions | Target 16.3: Promote the rule of law and ensure equal access to justice for all. | Proportion of legal decisions influenced by psychopathy assessments. The article states the label has a “very heavy weight on their decision-making,” undermining equal justice. |

| SDG 16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions | Target 16.6: Develop effective, accountable and transparent institutions. | Rate at which legal and clinical practices are updated to reflect new scientific evidence. The article highlights a failure of accountability, as experts “still go into court today and say exactly the same thing, as if the research hasn’t changed.” |

Source: news.uchicago.edu

What is Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0