Bad wealth made good: how to tackle Britain’s twin faultlines of low growth and rising inequality – The Conversation

Report on Wealth Creation and its Alignment with Sustainable Development Goals

Introduction

Wealth creation has been identified as a primary mission for national progress. However, the nature of this wealth creation is critical. A distinction must be drawn between wealth generated through productive, innovative activities that support societal well-being and wealth accumulated through non-productive or extractive means. This report analyses this dichotomy, focusing on the implications for achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly within the context of the United Kingdom’s economy.

The Duality of Wealth: Productive vs. Extractive Accumulation

“Good” Wealth: A Driver for Sustainable Development

Productive wealth creation, or “good” wealth, stems from activities that enhance economic and social resilience. This form of wealth directly contributes to several SDGs:

- SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth): Generated through innovation, investment, and enhanced business productivity, it fosters sustainable economic growth.

- SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure): Investment in technology, science, and essential infrastructure like transport and local services strengthens a nation’s resources.

- SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being): Investments in medical technology and accessible care services improve public health outcomes.

This type of wealth creation ensures that economic gains are widely distributed, promoting inclusive growth and societal strength.

“Bad” Wealth: An Obstacle to the 2030 Agenda

Conversely, “bad” wealth accumulation is associated with non-productive activities that actively undermine progress towards the SDGs. This form of wealth has become increasingly prevalent over the last fifty years.

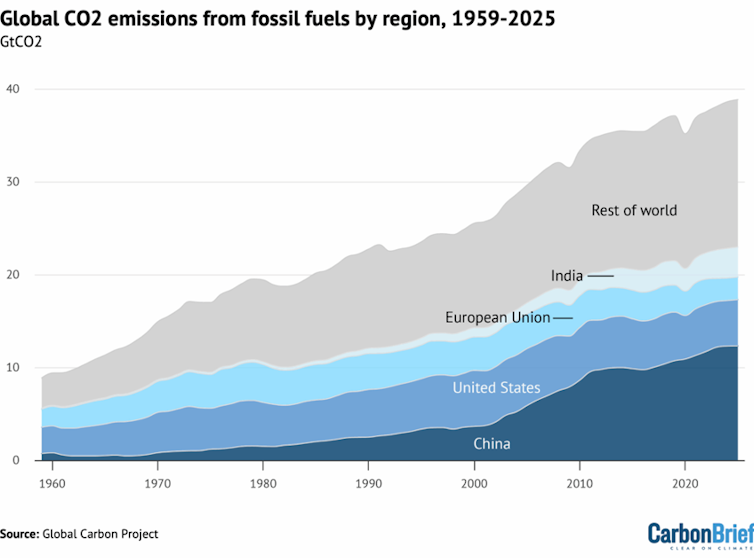

- SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities): “Bad” wealth is linked to economic extraction, where powerful capital owners capture excessive gains, exacerbating inequality. Globally, from the mid-1990s to 2021, the top 1% captured 38% of wealth growth, while the bottom 50% received only 2%.

- SDG 1 (No Poverty): This concentration of resources leads to social scarcity and growing impoverishment, diverting resources from basic needs to serve corporate elites.

- SDG 16 (Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions): Activities such as rigging financial markets, anti-competitive mergers, and manipulating corporate balance sheets weaken economic institutions and social resilience.

A significant portion of this wealth comes from passive activities, such as rising asset prices, particularly in property, which traps capital and prevents its reinvestment into the productive economy, hindering progress on SDG 8.

Analysis of Wealth Dynamics in the United Kingdom

The Productivity and Wealth Paradox

Since 2008, the UK has experienced stagnant economic growth and a persistent “productivity puzzle.” Despite this, private wealth holdings have surged, with total UK wealth now exceeding six times the size of the national economy, a twofold increase since the 1970s. This disconnect indicates that wealth accumulation is not being driven by dynamic, innovative economic activity aligned with SDG 8, but rather by asset inflation and rent-seeking behaviours.

Erosion of Common Wealth and Public Services

The trend towards privatisation has significantly impacted the UK’s common wealth and its ability to meet key SDGs.

- Publicly owned assets as a share of GDP have fallen from approximately 30% in the 1970s to around 10% today. This has weakened public finances and transferred control over essential services to private entities.

- SDG 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation): The privatised water industry serves as a case study in extractive practices, marked by under-investment, environmental damage from sewage dumping, and profits being prioritised over public service.

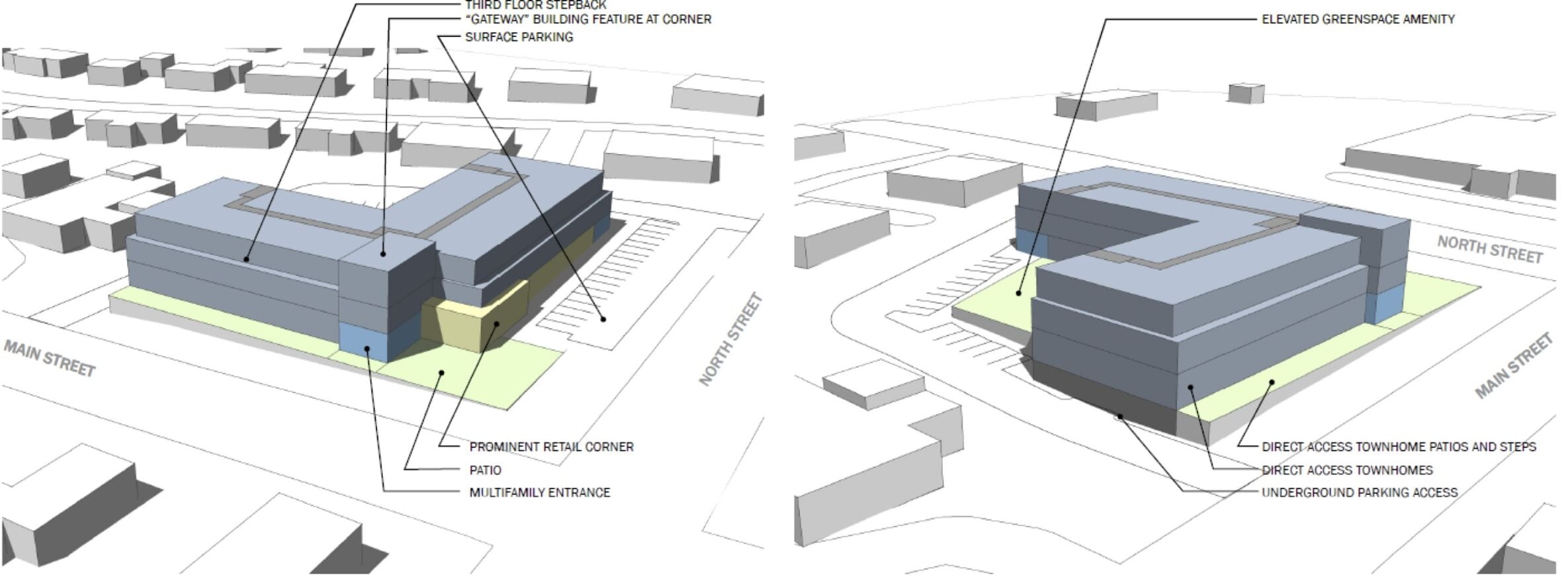

- SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities): The decline in home ownership, from a peak of 71% in 2000 to 65% in 2024, particularly among young adults, undermines the goal of creating inclusive and sustainable communities. Access to housing is increasingly dependent on inherited wealth, further entrenching inequality (SDG 10).

Policy Recommendations for Sustainable and Equitable Wealth Creation

To reverse these trends and align wealth creation with the SDGs, a series of structural reforms are necessary. The following six interventions provide a framework for transforming “bad” wealth into “good” wealth.

-

Shift the Tax Focus from Income to Wealth

The current tax system disproportionately burdens income from labour over wealth. Rebalancing this is crucial for achieving SDG 10. This includes reforming property taxes to be more progressive, which would also support SDG 11 by addressing housing affordability. Aligning capital gains tax rates with income tax rates would further this goal and strengthen fiscal institutions (SDG 16).

-

Reduce Wealth Transmission Through Inheritance

Inheritance perpetuates inequality and does little to boost productive activity. With intergenerational wealth transfers projected to increase significantly, reforming inheritance tax is essential to break the cycle of disadvantage and promote a more meritocratic society, in line with SDG 10. Idle assets could be redirected towards productive investments that support SDG 8.

-

Introduce a Comprehensive Wealth Tax

A modest annual tax on the largest wealth holdings could generate significant revenue. These funds could be earmarked for under-resourced public services, directly supporting SDG 1 (No Poverty), SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being), and SDG 4 (Quality Education). Public support for such a measure is high, presenting a viable political path.

-

Increase Public and Social Ownership of Utilities and Services

To counter the negative impacts of privatisation, a greater level of common ownership and more effective regulation are required. This would ensure that essential utilities, such as water, are managed in the public interest, directly addressing SDG 6. Tackling anti-competitive behaviour and price gouging would strengthen markets and institutions, contributing to SDG 16.

-

Establish Citizens’ Wealth Funds

To ensure all citizens benefit from economic activity, national and local “citizens’ wealth funds” could be created. These funds, owned collectively, would distribute returns as universal dividends or reinvest them in public services. This model promotes inclusive growth (SDG 8) and directly reduces poverty and inequality (SDG 1 and SDG 10). Examples like the Alaska Permanent Fund demonstrate the model’s viability.

-

Expand Access to Asset Ownership Across Society

Deep structural reforms are needed to provide all citizens with a stake in the economy. Initiatives that grant every individual a modest financial inheritance, such as a revitalised Child Trust Fund, could be a powerful tool for reducing wealth inequality from birth and promoting democratic opportunity, directly supporting the ambitions of SDG 10.

Conclusion

The current model of wealth accumulation in the UK and other developed nations is increasingly misaligned with the principles of sustainable development. The widening gap between the wealthy and the rest of society undermines social cohesion and economic stability, posing a direct threat to the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals, especially SDG 10. Failure to implement bold reforms will have severe consequences for future generations. A strategic shift towards promoting “good” wealth and curbing “bad” wealth is not merely an economic necessity but a moral imperative for building a more equitable and sustainable future.

Analysis of the Article in Relation to Sustainable Development Goals

1. Which SDGs are addressed or connected to the issues highlighted in the article?

-

SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth

The article directly addresses economic growth, productivity, and the nature of wealth creation. It distinguishes between “good” wealth from productive activities and “bad” wealth from non-productive or extractive practices, which relates to the quality and sustainability of economic growth.

-

SDG 9: Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure

The text discusses the importance of investment in “medical and scientific technology” and social infrastructure like schools and hospitals. It also critiques the under-investment and deterioration of key utilities, such as the water industry, linking private profiteering to failing infrastructure.

-

SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities

This is the central theme of the article. It extensively details the widening wealth gap in the UK, the concentration of assets among the super-rich, and how economic policies have fueled inequality. The proposed solutions, such as tax reform and wealth redistribution, are aimed directly at reducing these inequalities.

-

SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities

The article highlights the crisis in housing, a key component of this goal. It provides data on declining home ownership rates, the difficulty for young people to access housing, and the failure of the “property owning democracy” promise, all of which impact the sustainability and inclusivity of communities.

-

SDG 16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions

The discussion on reforming the tax system to make it fairer and more effective relates to building strong institutions. The article also points to institutional failures, such as “mismanaged monetary policy,” “a failure of anti-trust laws,” and the “rigging of financial markets,” which undermine justice and accountability.

-

SDG 17: Partnerships for the Goals

The article’s focus on tax reform—specifically on shifting the tax burden from income to wealth through capital gains, inheritance, and property taxes—is directly related to strengthening domestic resource mobilization to finance sustainable development.

2. What specific targets under those SDGs can be identified based on the article’s content?

-

SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth

- Target 8.1: Sustain per capita economic growth. The article refers to Britain’s “dismal” economic record and “collapse in the rate of economic growth” since 2008.

- Target 8.2: Achieve higher levels of economic productivity. The text discusses Britain’s “productivity puzzle” and argues for wealth creation based on “innovation, investment and more productive business methods” rather than passive asset inflation.

-

SDG 9: Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure

- Target 9.1: Develop quality, reliable, sustainable and resilient infrastructure. The article critiques the state of the UK’s water industry, which under private ownership has suffered from “two decades of under-investment,” leading to “leaky and unrepaired pipes.” It also mentions using tax funds to “improve social infrastructure from schools to hospitals.”

-

SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities

- Target 10.1: By 2030, progressively achieve and sustain income growth of the bottom 40 per cent of the population at a rate higher than the national average. The article provides evidence to the contrary, stating that from the mid-1990s to 2021, “the bottom 50% received just 2%” of personal wealth growth.

- Target 10.3: Ensure equal opportunity and reduce inequalities of outcome. The article argues that “birth and inheritance remain the most powerful indicators… of where you end up in the wealth stakes,” directly challenging the principle of equal opportunity.

- Target 10.4: Adopt policies, especially fiscal, wage and social protection policies, and progressively achieve greater equality. The entire section “Six ways to turn bad wealth into good” is a detailed proposal for fiscal policies (tax reform on wealth, property, and inheritance) to reduce inequality.

-

SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities

- Target 11.1: By 2030, ensure access for all to adequate, safe and affordable housing. The article details the failure to meet this target, citing that the “rate of home ownership has shrunk,” getting on the housing ladder is “heavily dependent on having rich parents,” and a rising proportion of young people are priced “out of home ownership.”

-

SDG 16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions

- Target 16.6: Develop effective, accountable and transparent institutions at all levels. The call to reform the “least defensible tax in Britain” (the council tax) and create a fairer, more progressive tax system is an appeal to build more effective and accountable fiscal institutions.

-

SDG 17: Partnerships for the Goals

- Target 17.1: Strengthen domestic resource mobilization… to improve domestic capacity for tax and other revenue collection. The proposals to reform capital gains tax, inheritance tax, and introduce a progressive property tax are all methods to enhance domestic revenue collection by taxing wealth more effectively.

3. Are there any indicators mentioned or implied in the article that can be used to measure progress towards the identified targets?

Yes, the article provides several specific statistics that can serve as indicators to measure the issues discussed.

-

For SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities):

- Indicator: Share of wealth growth captured by different wealth groups. The article states that globally, from the mid-1990s to 2021, “the top 1% of wealth holders captured 38% of the growth in personal wealth, while the bottom 50% received just 2%.”

- Indicator: Ratio of wealth of the richest individuals to the average person. In the UK, this grew from “6,000 times the average person in 1989 to 18,000 times in 2023.”

- Indicator: Differential tax rates on income versus wealth. The article notes that in the UK, “Income from work is taxed at an average of around 33% and wealth at less than 4%.”

- Indicator: Proportion of estates paying inheritance tax. This is used to show how little wealth is taxed, with “Only 4.6% of deaths in the UK resulted in an inheritance tax charge in the 2023 financial year.”

-

For SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities):

- Indicator: Home ownership rate. The article tracks its decline in the UK “from a peak of 71% in 2000 to 65% in 2024.”

- Indicator: Proportion of young adults living with their parents. This is used as a measure of housing inaccessibility, noting the proportion of 18-34 year-olds living with parents “reached 28% in 2024.”

-

For SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) & SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure):

- Indicator: National wealth as a multiple of the national economy (GDP). The article states that UK wealth is now “more than six times the size of the country’s economy, up from three times in the 1970s,” suggesting wealth accumulation is outpacing productive economic growth.

- Indicator: Share of publicly owned assets as a percentage of GDP. This is used to measure the extent of privatization, having “fallen from around 30% in the 1970s to about a tenth.”

4. Table of SDGs, Targets, and Indicators

| SDGs | Targets | Indicators |

|---|---|---|

| SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth | 8.1: Sustain per capita economic growth. 8.2: Achieve higher levels of economic productivity. |

UK wealth as a ratio of GDP has increased from 3 times in the 1970s to over 6 times, while the economic growth rate has been “dismal.” |

| SDG 9: Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure | 9.1: Develop quality, reliable, sustainable and resilient infrastructure. | Publicly owned assets as a share of GDP have fallen from around 30% in the 1970s to about 10%, linked to under-investment in utilities like water. |

| SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities | 10.1: Sustain income growth of the bottom 40%. 10.3: Ensure equal opportunity. 10.4: Adopt fiscal policies for greater equality. |

The top 1% captured 38% of wealth growth, while the bottom 50% received 2%. The wealth of the richest 200 people is 18,000 times that of the average person. Income is taxed at ~33%, while wealth is taxed at Only 4.6% of deaths result in an inheritance tax charge. |

| SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities | 11.1: Ensure access for all to adequate, safe and affordable housing. | The home ownership rate has shrunk from 71% (2000) to 65% (2024). The proportion of young people (18-34) living with parents reached 28% in 2024. |

| SDG 16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions | 16.6: Develop effective, accountable and transparent institutions. | The article points to the need to reform the council tax system, which is still based on 1991 property values and is described as the “least defensible tax in Britain.” |

| SDG 17: Partnerships for the Goals | 17.1: Strengthen domestic resource mobilization. | Inheritance tax contributes only 0.7% of all tax receipts, indicating a low level of domestic resource mobilization from wealth transfers. |

Source: theconversation.com

What is Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0