De-Weaponising Food: Transnational Corridors for Global Food Security – orfonline.org

Report on Transnational Corridors for Global Food Security and Sustainable Development Goals

Introduction: Geopolitical Threats to SDG 2 (Zero Hunger)

The increasing use of economic statecraft has led to the weaponization of critical supply chains, including agricultural goods. This trend poses a direct threat to global food security and undermines the achievement of Sustainable Development Goal 2 (Zero Hunger). Geopolitical tensions and strategic leveraging of food supplies disrupt markets, destabilize prices, and jeopardize food access for vulnerable populations worldwide. This report analyzes these disruptions and evaluates the role of transnational food corridors as a mechanism to mitigate these risks and advance the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

Analysis of Supply Chain Disruptions and SDG Impacts

Recent geopolitical events have highlighted the vulnerability of global food systems, with significant negative consequences for multiple SDGs.

- US-China Trade Impasse: Retaliatory tariffs on agricultural goods, including soybeans, pork, and corn, were used to exert political pressure. This action disrupted trade flows and demonstrated how food can be instrumentalized in economic disputes, threatening the stable markets needed to support SDG 1 (No Poverty) and SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) for agricultural producers.

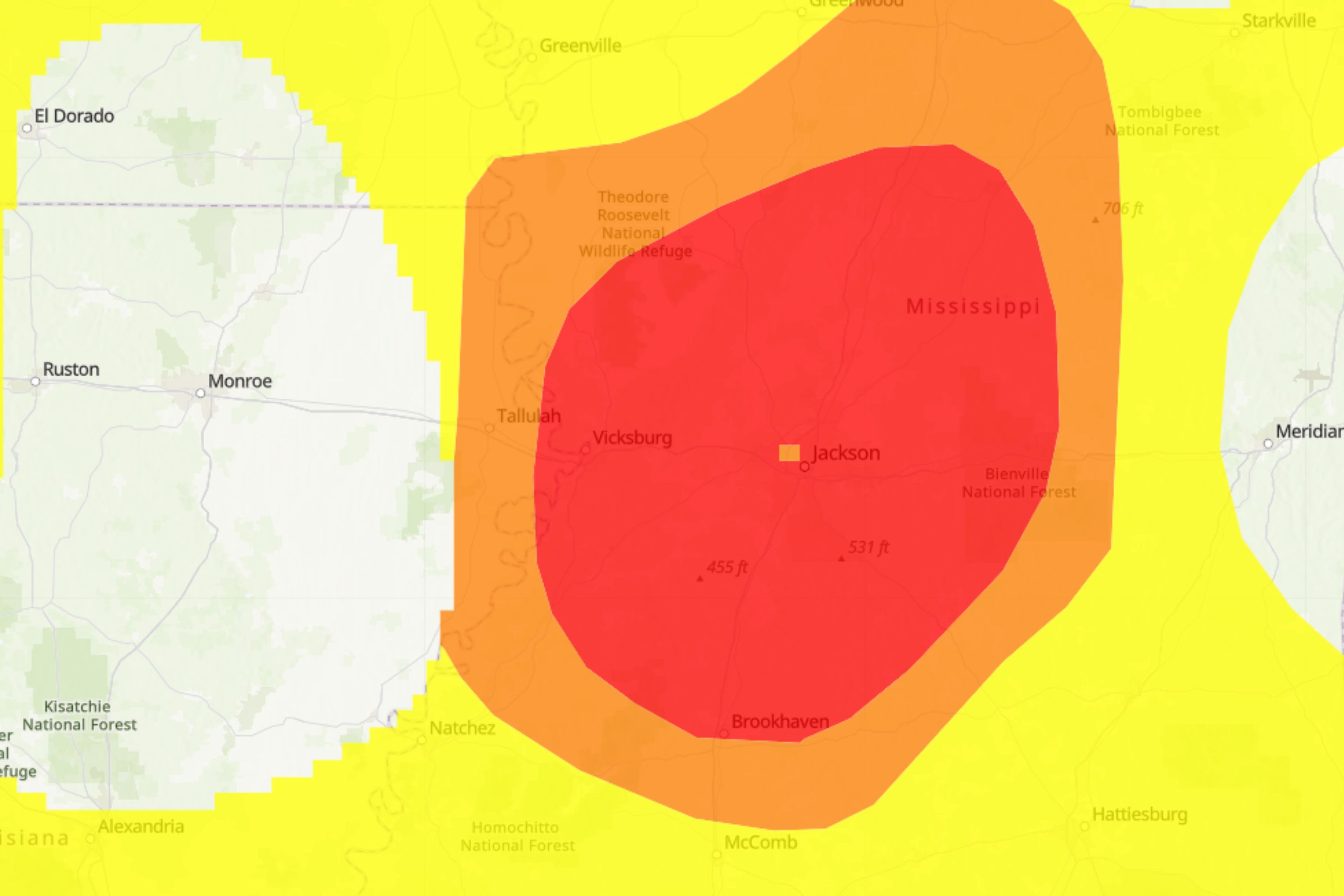

- Russia-Ukraine Conflict: The war caused severe disruptions to global supplies of wheat and sunflower oil, leading to price spikes that disproportionately affected import-dependent nations. This directly hampered progress on SDG 2 by increasing food insecurity and threatened regional stability, impacting SDG 16 (Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions).

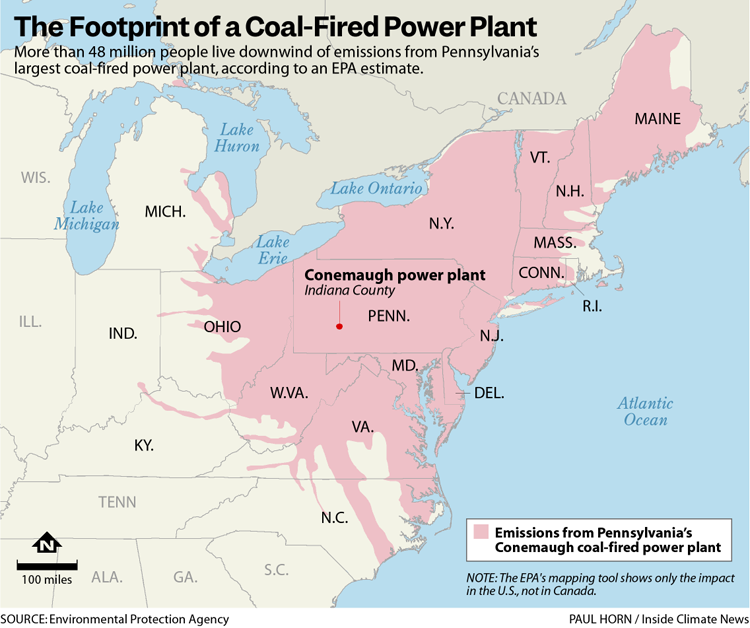

- Maritime Blockades: Attacks on shipping routes in the Red Sea created instability in food commodity markets, affecting both producers and consumers and highlighting the fragility of the infrastructure that underpins global food security, a key concern for SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure).

National Self-Sufficiency Policies vs. Global Trade for Sustainable Development

In response to these shocks, several nations are pursuing food self-sufficiency. However, this inward-looking approach presents risks to the global system.

- Risks of Protectionism: Policies aiming for ‘absolute self-sufficiency’ can amplify systemic risks and lead to long-term price uncertainty and market instability. This approach runs counter to the collaborative spirit of SDG 17 (Partnerships for the Goals).

- Benefits of Trade Liberalization: Research indicates that trade liberalization enhances food security by making products more affordable and encouraging dietary diversity, which is crucial for achieving the nutritional targets within SDG 2. A significant percentage of global staples like wheat (25%) and maize (14%) are traded across borders, underscoring the essential role of international trade in ensuring global food access.

Strategic Implementation of Food Corridors for SDG Advancement

Connecting Regions to Build Resilience and Foster Investment

Transnational food corridors, as a form of Spatial Development Initiative (SDI), offer a structured solution to build resilient and stable food systems. They directly contribute to several SDGs by creating an enabling environment for investment and connectivity.

Key Contributions to Sustainable Development:

- Investment and Infrastructure (SDG 9): Corridors attract public and private investment into essential infrastructure such as food parks, cold-chain logistics, irrigation, and roads. An estimated 50% increase in agricultural investment is required by 2050, and corridors provide a framework to channel these funds effectively.

- Economic Growth and Poverty Reduction (SDG 8 & SDG 1): By linking production zones to markets and reducing supply chain bottlenecks, corridors provide stable markets for farmers and agribusinesses. This stability encourages investment in value-added crops and processing, creating jobs and improving livelihoods. The proposed India-UAE food corridor exemplifies this, aiming to enhance food security while creating economic opportunities.

- Partnerships for the Goals (SDG 17): These corridors are built on cross-border cooperation, regulatory harmonization, and shared infrastructure, embodying the principles of global partnership. They facilitate harmonized customs documentation and mutually recognized sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) measures, easing trade.

Case Studies: Successful Implementation of Food Corridors

Existing corridors demonstrate significant benefits for food security and regional development.

- EU-Ukraine Solidarity Lanes: Established during the Russia-Ukraine conflict, these corridors served as a lifeline, enabling the export of 199 million tonnes of goods, primarily agricultural products. This initiative was critical for maintaining Ukraine’s economy and ensuring global food supplies, directly supporting SDG 2 and SDG 16.

- Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS) Corridor: This corridor has created climate-friendly agro-based value chains by improving last-mile connectivity and cross-border logistics. By reducing post-harvest losses, it enhances food security and boosts farmer incomes, contributing to SDG 2 and SDG 8.

- African Agricultural Corridors: Initiatives like the Beira Agricultural Growth Corridor (BAGC) in Mozambique and the Southern Agricultural Growth Corridor of the United Republic of Tanzania (SAGCOT) connect agricultural heartlands to ports, transforming regional value chains.

Conclusion: De-Weaponizing Food to Secure the 2030 Agenda

At a time when food is increasingly used as a bargaining chip in diplomatic standoffs, transnational food corridors offer a powerful mechanism to reclaim leverage and de-weaponize essential supply chains. By diversifying trade routes, promoting regional alignment, and enhancing transparency, these corridors create safeguards against economic coercion. Ensuring food security is a global public good and a prerequisite for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. The strategic development of food corridors is essential for stabilizing food systems and preventing the exploitation of statecraft, thereby securing progress towards SDG 2, SDG 16, and SDG 17.

Analysis of Sustainable Development Goals in the Article

1. Which SDGs are addressed or connected to the issues highlighted in the article?

-

SDG 2: Zero Hunger

- The entire article is centered on global food security, which is the primary objective of SDG 2. It discusses threats to food supply chains, such as geopolitical conflicts and trade restrictions, and proposes solutions like transnational food corridors to ensure food availability, stabilize prices, and improve access to food, particularly for import-dependent nations.

-

SDG 9: Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure

- The article strongly advocates for the development of resilient and transborder infrastructure as a solution to food insecurity. It highlights the role of “dedicated food corridors” which involve significant investment in physical connectivity, logistics, processing hubs, cold-chain facilities, roads, and ports to create stable and efficient agricultural value chains.

-

SDG 17: Partnerships for the Goals

- The concept of transnational food corridors, such as the proposed India-UAE corridor or the existing EU-Ukraine Solidarity Lanes, is fundamentally based on international cooperation and partnerships. The article emphasizes the need for regional alignment, regulatory harmonization, and multi-stakeholder collaboration (involving governments and private companies like DP World) to de-weaponize food and ensure global food security.

-

SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth

- The development of food corridors is presented as a driver of economic growth. The article notes that such initiatives attract investment, create agribusiness opportunities, provide stable markets for farmers, and encourage investment in value-added crops and processing activities, thereby contributing to economic development in the participating regions.

-

SDG 16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions

- The article’s premise is the “weaponisation of food” through economic statecraft, trade wars, and blockades during conflicts. This directly relates to the goal of promoting peaceful societies. The proposed food corridors are a mechanism to build resilience against such coercive tactics and prevent the exploitation of food supply chains, thus contributing to stability.

2. What specific targets under those SDGs can be identified based on the article’s content?

-

Under SDG 2 (Zero Hunger):

- Target 2.b: Correct and prevent trade restrictions and distortions in world agricultural markets. The article directly addresses this by criticizing retaliatory tariffs (US-China trade impasse) and export restrictions, arguing that food corridors can ensure an “uninterrupted flow of agricultural goods” and “de-weaponise food.”

- Target 2.c: Adopt measures to ensure the proper functioning of food commodity markets… to help limit extreme food price volatility. The article discusses how disruptions like the Russia-Ukraine war led to “price spikes” and “instability in food commodity markets.” Food corridors are proposed as a mechanism to “stabilise prices.”

-

Under SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure):

- Target 9.1: Develop quality, reliable, sustainable and resilient infrastructure, including regional and transborder infrastructure, to support economic development and human well-being. This is the core proposal of the article. It explicitly calls for “transnational corridors,” “physical connectivity,” and investment in “irrigation, electrification, and roads,” as well as “food parks and cold-chain logistics” to create resilient supply chains.

-

Under SDG 17 (Partnerships for the Goals):

- Target 17.11: Significantly increase the exports of developing countries. The article explains that corridors like the proposed India-UAE one would “provide stable markets for Indian producers,” and corridors in Africa (BAGC, SAGCOT) connect agricultural regions to ports, facilitating exports.

- Target 17.16: Enhance the global partnership for sustainable development, complemented by multi-stakeholder partnerships. The creation of corridors involves partnerships between multiple countries (e.g., the Greater Mekong Subregion program) and between public and private sectors (e.g., UAE-based companies investing in Indian logistics).

3. Are there any indicators mentioned or implied in the article that can be used to measure progress towards the identified targets?

-

Volume and Value of Trade:

- The article provides concrete data for the EU-Ukraine Solidarity Lanes, stating they allowed for “trade worth EUR 61 billion and 199 million tonnes of goods (mostly agricultural products) exported.” This serves as a direct indicator of a corridor’s effectiveness in maintaining trade flows (relevant to Targets 2.b and 17.11).

-

Level of Investment in Agriculture:

- The article implies an investment indicator by highlighting a significant funding gap. It states that “investment in agriculture needs to be increased by 50 percent or US$83 billion per year by 2050.” Progress can be measured by tracking annual investment flows into agricultural infrastructure (relevant to Target 9.1).

-

Reduction of Trade Barriers:

- The article mentions the US reducing “overall tariffs on Chinese goods from 57 percent to 47 percent” as part of a trade deal. The level of tariffs and non-tariff barriers (like customs documentation, which corridors help harmonize) is an indicator of progress towards preventing trade restrictions (relevant to Target 2.b).

-

Food Price Stability:

- The article refers to “price spikes” and “instability” as negative outcomes of supply chain disruptions. An implied indicator is the volatility of food commodity prices. The success of food corridors could be measured by their ability to contribute to more stable prices for staples like wheat and sunflower oil in global and local markets (relevant to Target 2.c).

4. Summary Table of SDGs, Targets, and Indicators

| SDGs | Targets | Indicators |

|---|---|---|

| SDG 2: Zero Hunger |

2.b: Correct and prevent trade restrictions and distortions in world agricultural markets.

2.c: Adopt measures to ensure the proper functioning of food commodity markets and limit extreme food price volatility. |

– Reduction in tariff levels on agricultural goods (e.g., US tariffs on Chinese goods reduced from 57% to 47%). – Harmonization of customs documentation and sanitary/phytosanitary (SPS) measures. – Reduced volatility in food commodity prices (moving away from “price spikes” and “instability”). |

| SDG 9: Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure | 9.1: Develop quality, reliable, sustainable and resilient infrastructure, including regional and transborder infrastructure. |

– Annual investment in agriculture and related infrastructure (measured against the required increase of “US$83 billion per year”). – Development of specific infrastructure like “food parks,” “cold-chain logistics,” “farm road networks,” and “cross-border logistics hubs.” |

| SDG 17: Partnerships for the Goals |

17.11: Significantly increase the exports of developing countries.

17.16: Enhance the global partnership for sustainable development. |

– Volume of goods exported through corridors (e.g., “199 million tonnes” via Solidarity Lanes). – Value of trade enabled by corridors (e.g., “EUR 61 billion” via Solidarity Lanes). – Number of multi-country and public-private partnership agreements for establishing food corridors. |

Source: orfonline.org

What is Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0