How eDNA Technology is Changing the Game for Protecting Ocean Species

Environmental DNA (eDNA) is used to monitor biodiversity by analyzing genetic material in water samples. It offers rapid insights into ecosystems, helps detect invasive species, and tracks climate change effects. Challenges include standardization and database limitations, but ongoing innovation expands its applications beyond biodiversity studies.

Author: Annika Hammerschlag in Banc D’Arguin, Mauritania

Hanging over the side of the boat, Nahi El Bar Jiyed scoops up a jug of sea water, then carefully pours it into a large syringe. While the sample may seem ordinary, to the biologist it’s a trove of secrets: the DNA of every living creature swimming below.

He presses the water sample through a filter about the size of his hand, which captures the DNA fragments, then repeats the process several more times. Meters away, a sea turtle emerges for a breath then retreats to the seagrass meadow below.

“Without disturbing the environment, we can take a sample that tells us exactly what was at this site,” Jiyed says.

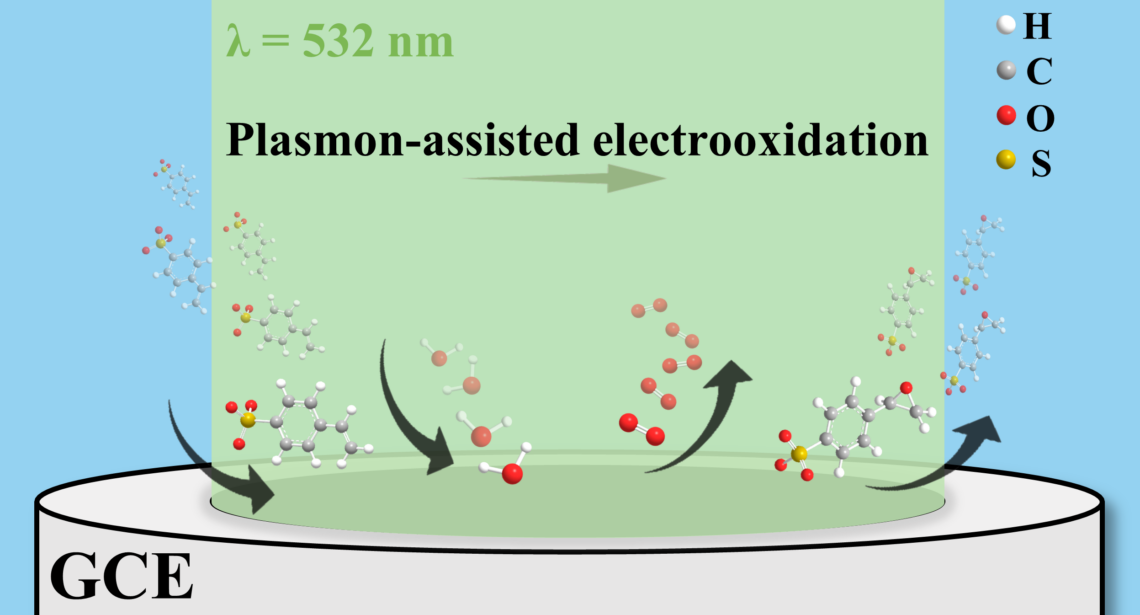

Over the past decade, the use of environmental DNA – known as “eDNA” – to monitor biodiversity has surged. As animals move through their environment, they shed fragments of genetic material: skin cells, waste products and other body fluids. By extracting these minute traces of DNA from samples of water, soil or air, scientists can determine the presence and diversity of species with unprecedented accuracy, providing a snapshot of the intricacies of an ecosystem.

“Knowledge is the basis of all management. If you don’t know a place, you can’t protect it,” Jiyed says. “It’s the first step.” His efforts are part of a Unesco initiative to collect eDNA across 22 marine world heritage sites, including Mauritania’s Banc d’Arguin national park, where he works.

The park is nestled along the country’s north coast, where Saharan sand dips into emerald waters. Fishing boats propelled only by sail glide past low-lying islands. The penetrating silence is misleading: this place is home to endangered dolphins and sea turtles and is a vital stopover for millions of migratory birds. Due to its remarkable biodiversity, the park was granted world heritage status by Unesco in 1989.

It’s a “true biogeographic crossroads”, which marks the meeting of tropical and temperate organisms, says the park director, Ebaye Sidina. “We know that we have an enormous number of species, and the DNA analysis will finally lift the veil and show that this diversity is there and must be preserved,” he says.The eDNA technology not only allows scientists to assess biodiversity, but to detect invasive species, track endangered or elusive animals and to monitor wastewater for diseases and pathogens. It has even uncovered the existence of species previously thought to be extinct. At Banc d’Arguin, scientists are eager to see if there’s any indication of the smalltooth sawfish, which Sidina said hasn’t been seen in decades.

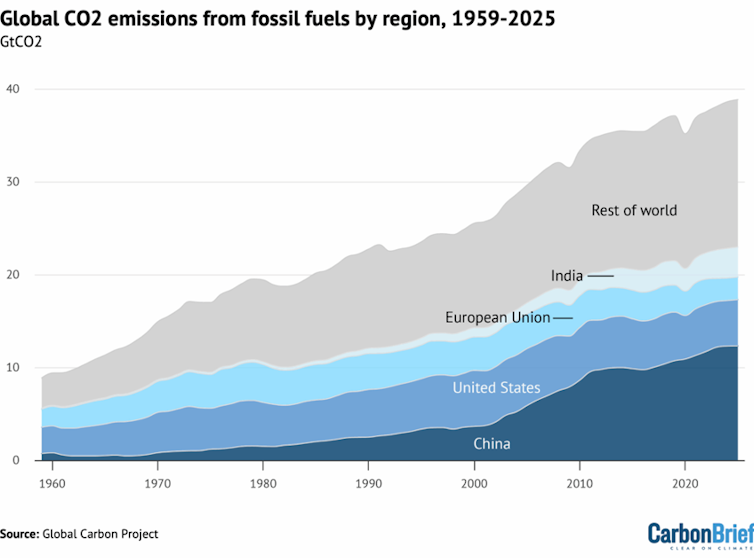

Used over time, eDNA can provide insights into how the climate crisis is affecting populations, such as by shifting their geographic range.

“Several fish species are already moving 25km every decade, either to deeper waters or further from the equator,” says Fanny Douvere, the head of the world heritage marine programme at Unesco. “We want to make sure that in another 30 to 40 years, the boundaries of these marine world heritage sites will still be relevant.”

Analysis of eDNA offers several advantages over traditional surveys, particularly when assessing the effects of climate changes on an ecosystem. Whereas traditional surveys can take years to complete, eDNA analysis can yield results within months, says Ward Appeltans, the head of the ocean biodiversity information system at Unesco and science coordinator of the eDNA expeditions initiative.

“The ocean’s status is changing so rapidly,” he says. “We want to know what its status is now, not five years ago.”

The ability to detect immediate changes is also crucial for tracking invasive species, such as lionfish, which can quickly overtake native fish populations. Moreover, eDNA sampling offers a noninvasive alternative to harmful standard survey methods, such as bottom trawling and the capturing, tranquilising and tagging of animals.

“eDNA will also pick up things that you maybe wouldn’t have seen because they were hiding or only show up at certain times of day,” says Luke Thompson, a researcher at Mississippi State University and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in Miami, Florida. Traditional marine and aerial surveys also tend to be far more expensive, as they require boats, helicopters, planes and crew.

However, eDNA technology does present its own challenges. Ocean currents can prevent species in the sample region from being detected, or cause others in far-off areas to appear present. Some animals shed more DNA than others, which can paint an inaccurate picture of population ratios.

“But the main limitation is the lack of consensus about standardising methods and markers,” says Louis Bernatchez, the editor-in-chief of the scientific journal Environmental DNA.

In order to match collected DNA to the corresponding species, scientists run the genetic sequences through a reference database. However, a unified global database does not exist, and there’s no consensus regarding which genetic markers to use. As it is, less than 1% of all animals have had their genomes sequenced.

“People aren’t sufficiently working together,” Bernatchez says. “It’s a big problem.” Unesco, for its part, plans to upload all data from its eDNA initiative to its open science marine species database.

Despite the drawbacks, scientists around the globe continue to apply the technology in innovative ways. In the Arctic, DNA from polar bear tracks is being used to monitor population size and movement patterns – information that could inform conservation efforts and help mitigate human-bear interactions.

Across North America and Europe, eDNA samples from flowers have revealed animals and insects previously unknown to be pollinators. And in the field of forensics, scientists have found that DNA extracted from the blood of mosquitoes at crime scenes can accurately identify victims and suspects.

“There’s a countless diversity of molecules that are waiting to tell us what’s going on and what they’re doing out there,” says Thompson. “It’s a great way to think about it.”

What is Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0