The EAT–Lancet Commission on healthy, sustainable, and just food systems.

Executive summary

The global context has shifted dramatically since publication of the first EAT–Lancet Commission in 2019, with increased geopolitical instability, soaring food prices, and the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbating existing vulnerabilities and creating new challenges. However, food systems remain squarely centred at the nexus of food security, human health, environmental sustainability, social justice, and the resilience of nations. Actions on food systems strongly impact the lives and wellbeing of all and are necessary to progress towards goals highlighted in the Sustainable Development Goals, the Paris Agreement, and the Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework. Although current food systems have largely kept pace with population growth, ensuring sufficient caloric intake for many, they are the single most influential driver of planetary boundary transgression. More than half of the world's population struggles to access healthy diets, leading to devastating consequences for public health, social equity, and the environment. Although hunger has declined in some regions, recent increases linked to expanding conflicts and emergent climate change impacts have reversed this positive trend. Obesity rates continue to rise globally, and the pressure exerted by food systems on planetary boundaries shows no signs of abating. In this moment of increasing instability, food systems still offer an unprecedented opportunity to build the resilience of environmental, health, economic, and social systems, and are uniquely placed to enhance human wellbeing while also contributing to Earth-system stability.

This updated analysis builds upon the 2019 EAT–Lancet Commission, expanding its scope and strengthening its evidence base. The first Commission defined food group ranges for a healthy diet and identified the food systems' share of planetary boundaries. In this Commission, we add an analysis of the social foundations for a just food system, and incorporate new data and perspectives on distributive, representational, and recognitional justice, providing a global overview on equity in food systems. Substantial improvements in modelling capacity and data analysis allow for the use of a multimodel ensemble to project potential outcomes of a transition to healthy and sustainable food systems.

The planetary health diet (PHD) remains a cornerstone of our recommendations and can be seen as a framework within which diverse and culturally appropriate diets can exist. Robust updated evidence reinforces a strong association with improved health outcomes, large reductions in all-cause mortality, and a substantial decline in the incidence of major diet-related chronic diseases. The reference PHD emphasises a balanced dietary pattern that is predominantly plant-based, with moderate inclusion of animal-sourced foods and minimal consumption of added sugars, saturated fats, and salt. Successful implementation of the PHD requires careful consideration of cultural contexts and the promotion of culturally appropriate and sustainable dietary traditions. This diversity of contexts, bounded by the PHD's reference values, represents substantial flexibility and choice across cultures, geographies, and individual preferences. However, when confronted by climate, biodiversity, health, and justice crises, transformation will require urgent and meaningful changes in our individual and collective behaviours and our culture of unhealthy, unjust, and unsustainable food production and consumption.

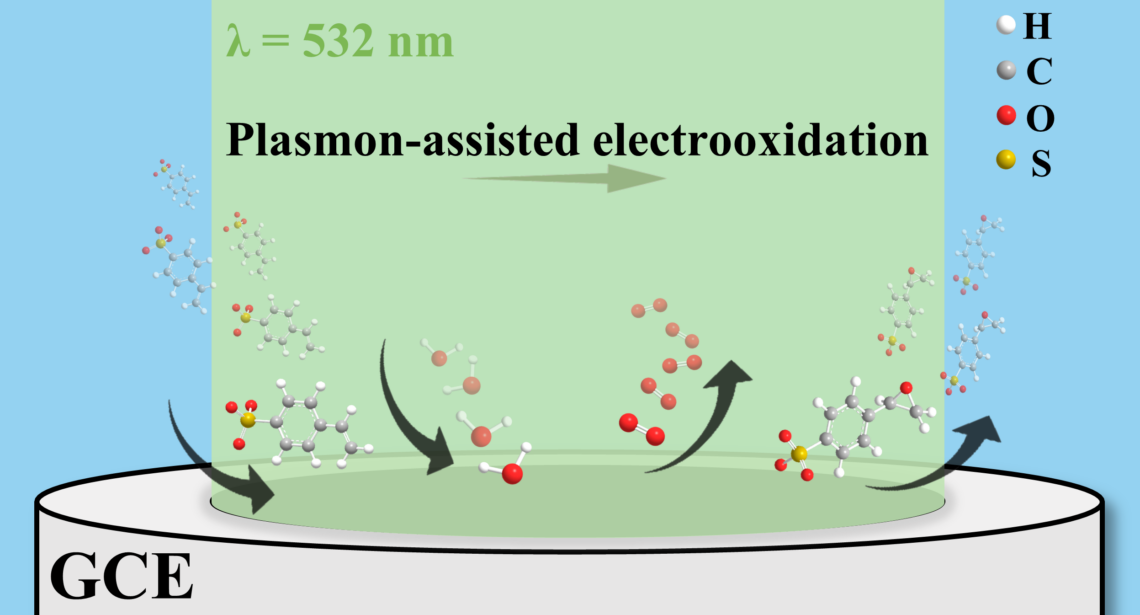

For the first time, we quantify the global food systems' share of all nine planetary boundaries. These food system boundaries confirm that food is the single largest cause of planetary boundary transgressions, driving the transgression of five of the six breached boundaries. In addition, food systems exert a notable impact on the transgressed climate boundary and on the ocean acidification boundary. Unsustainable land conversion, particularly deforestation, remains a major driver of biodiversity loss and climate change, highlighting the need for zero conversion of all remaining intact ecosystems. Food systems account for the near totality of nitrogen and phosphorus boundary transgression, emphasising the improvements needed in nutrient management, efficient nutrient redistribution, and circular nutrient systems. The massive use of novel entities in food production, processing, and packaging (ranging from plastics to pesticides) remains a major concern but is alarmingly understudied.

Our assessment of justice integrates three dimensions—distributive, representational, and recognitional—within a human rights framing that includes the rights to food, a healthy environment, and decent work. Analyses reveal important inequities in access to healthy diets, decent work conditions, and healthy environments, disproportionately affecting marginalised groups in low-income regions. We therefore propose nine social foundations that enable these rights to be met, and are able to assess the global status of six. Enabling access to, affordability of, and demand for healthy diets is paramount. Equally crucial is the right to live and work within a non-toxic environment and a stable climate system, as we recognise the profound impact of environmental degradation on human health and wellbeing. Furthermore, a living wage and meaningful representation would allow individuals to actively participate in building healthy, sustainable, and just food systems. However, nearly half of the world's population falls below these social foundations, undermining their ability to meet basic human rights. At the same time, the dietary patterns of most (6·9 billion people) of the world exert pressures that threaten further planetary boundary transgression. The destabilising effect of unhealthy overconsumption on the Earth's systems highlights the importance of viewing healthy diets not just as a human right, but also as a shared responsibility.

Scenario results from an ensemble of 11 global food system models across multiple scenarios reveals the substantial potential for reducing negative environmental and health effects through dietary shifts, improved and increased agricultural productivity, and reductions in food loss and waste. Creating demand for and increasing adoption of diets that adhere to the PHD, coupled with ambitious climate mitigation policies, would result in substantial reductions in greenhouse gas emissions and land use. The results of this modelling excercise are sobering, showing that even with these ambitious transformations (ie, improved and increased agricultural productivity, reduced food loss and waste, and a transition to eating within the PHD), the world is barely able to return to the safe space for freshwater use and climate change, and continues to transgress the biogeochemical boundary for nitrogen and phosphorus loading—albeit with substantially reduced pressure.

Analyses focusing on sustainable and ecological intensification of food production practices, along with more circular nutrient systems, suggest that widespread adoption of these practices could reduce further greenhouse gas emissions, increasing carbon sequestration; reduce the land footprint dedicated to food production; decrease water footprints; and make substantial progress in addressing nitrogen and phosphorus boundary transgressions, even with a growing global population and increased food consumption.

To advance towards the goals of healthy (through the PHD), sustainable (within food system boundaries), and just (above social foundations) food systems by 2050, we propose eight priority solutions, each accompanied by specific actions and policy measures: (1) create food environments to increase demand for healthy diets, ensuring they are more accessible and affordable; (2) protect and promote healthy traditional diets; (3) implement sustainable and ecological intensification practices; (4) apply strong regulations to prevent loss of remaining intact ecosystems; (5) improve infrastructure, management, and consumer behaviour change to reduce food loss and waste; (6) secure decent working conditions; (7) ensure meaningful representation for all; and (8) recognise and protect marginalised groups. These proposed solutions and actions should be organised into coherent bundles to enhance political feasibility and policy effectiveness. The most suitable and effective bundles will vary by context and should be tailored to the specific challenges and opportunities of each region and sector.

This Commission reinforces the urgent need for a great food transformation. The targets of the EAT–Lancet Commission for healthy people on a healthy planet with just food systems can only be met through concerted global action and unprecedented levels of transformative change. The Commission calls for cross-sectoral coalitions that develop context-specific roadmaps, aligning with existing and emerging global frameworks, such as the Paris Agreement, the Convention on Biological Diversity, and the post-2030 Sustainable Development Goals agenda. These roadmaps include the setting of science-based targets with monitoring and accountability mechanisms in place. Mechanisms should be established to shield policy making from undue corporate influence, and civil society and social movements have an important role in promoting transparency and oversight.

Key messages

- Food systems sit at the nexus of health, environment, climate, and justice. A food systems transformation is fundamental for solving crises related to the climate, biodiversity, health, and justice. The central position of food systems emphasises the interdependent nature of these crises, rather than each crisis separately, which highlights the need to position food systems change as a global integrator across economic, governance, and policy domains.

- The updated planetary health diet (PHD) has an appropriate energy intake; a diversity of whole or minimally processed foods that are mostly plant sourced; fats that are primarily unsaturated, with no partially hydrogenated oils; and small amounts of added sugars and salt. The diet allows flexibility and is compatible with many foods, cultures, dietary patterns, traditions, and individual preferences. The PHD also provides nutritional adequacy and diminishes the risks of non-communicable diseases. At present, all national diets deviate substantially from the PHD, but a shift to this pattern could avert approximately 15 million deaths per year (27% of total deaths worldwide). Such a transition would reduce the rates of many specific non-communicable diseases and promote healthy longevity.

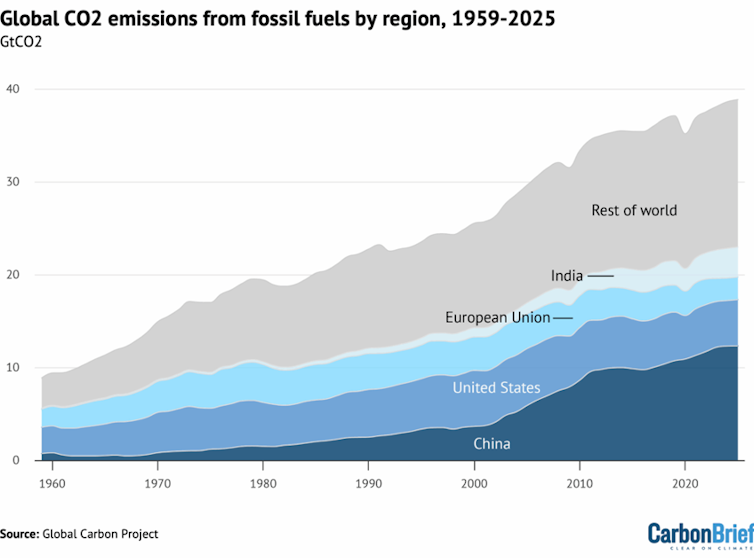

- Food drives five planetary boundary transgressions, including land system change, biosphere integrity, freshwater change, biogeochemical flows, and approximately 30% of greenhouse gas emissions driving climate change. How and where food is produced, which foods are produced and consumed, and how much is lost and wasted, all contribute to planetary boundary transgressions. No safe solution to climate and biodiversity crises is possible without a global food systems transformation. Even if a global energy transition away from fossil fuels occurs, food systems will cause the world to breach the Paris Climate agreement of limiting global mean surface temperature to 1·5°C.

- Human rights related to food systems (ie, the rights to food, a healthy environment, and decent work) are not being met, with nearly half the world's population below the social foundations for these rights. Meanwhile, responsibility for planetary boundary transgressions from food systems is not equal: the diets of the richest 30% of the global population contribute to more than 70% of the environmental pressures from food systems. Just 1% of the global population is in a safe and just space. These statistics highlight the large inequalities in the distribution of both benefits and burdens of current food systems. National policies that address inequities in the distribution of benefits and burdens of current food systems would aid in ensuring food-related human rights are met.

- The PHD needs to be available, affordable, convenient, aspirational, appealing, and delicious. To increase demand for healthy sustainable diets and enable necessary dietary shifts, food environment interventions, next-generation culinary research and development, increased purchasing power, and protection and promotion of healthy traditional diets are important actions.

- A food systems transformation following recommendations from the EAT–Lancet Commission—which include a shift to healthy diets, improved and increased agricultural productivity, and reduced food loss and waste—would substantially reduce environmental pressures on climate, biodiversity, water, and pollution. However, no single action is sufficient to ensure a healthy, just, and sustainable food system. Comparing 2050 values with the current state (as of 2020), a shift to healthy diets in isolation could lead to a 15% reduction in agricultural emissions, compared with a 20% reduction when all three actions are implemented simultaneously with improvements in productivity and food loss and waste. Individually, all three actions modestly reduce future nitrogen and phosphorous use (ie, a 27–34% increase by 2050 with individual actions vs a 41% increase under the business-as-usual scenario); however, in combination they substantially reduce future growth in nitrogen and phosphorous use (ie, a 15% increase compared with 2020 levels of use).

- Additional environmental benefits are accrued through sustainable and ecological intensification practices. Unprecedented investments and effort in these practices could potentially result in a net-zero food system. A diversity of context-specific practices can sequester additional carbon biomass, create and connect habitats, reduce nutrient applications, and increase the interception and capture of excessive crop fertiliser before it pollutes groundwater and surface water systems. These practices can be enabled by securing equitable access to land and water resources, strengthening public advisory services, addressing structural imbalances between producers and dominant agribusinesses, and through public and private sector investments that support farmers shifting towards sustainable practices.

- A food systems transformation following recommendations from the EAT–Lancet Commission could lead to a less resource-intensive and labour-intensive food system that can supply a healthy diet for 9·6 billion people, with modest impacts on average food costs. However, such a transformation would have profound implications for what, how, and where food is produced, and for people involved in these processes. For example, as a part of this restructuring, some sectors would need to contract (eg, a 33% reduction in ruminant meat production) and others would need to expand (eg, a 63% increase in fruit, vegetable, and nut production) compared with 2020 production levels.

- Justice is needed to unlock and accelerate action for transformation. A fair distribution of opportunities and resources—such that the rights to food, a healthy environment, and decent work are met, and distribution of the responsibility to produce, distribute, and consume healthy diets within planetary boundaries is fair—are the basis of a successful food systems transformation. Power asymmetries and discriminatory social and political structures prevent these rights from being met, which results in harms to people's health, precarious livelihoods for food systems workers, and lack of voice, undermining freedom, agency, and dignity. Ensuring liveable wages and collective bargaining, while regulating and limiting market concentration and improving transparency, accountability, representation, and access to information, are all impactful actions. We emphasise the protection of basic human rights in conflict areas as a fundamental foundation of justice.

- Unprecedented levels of action are required to shift diets, improve production, and enhance justice. A just transformation requires building coalitions with actors from inside and outside the food system, identifying bundles of actions, developing national and regional roadmaps for implementation, unlocking finance for the transformation, and rapidly putting joint plans into action. Such efforts should closely align with other sustainability and health initiatives (eg, the Paris Agreement, Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, and nation-specific food-based dietary guidelines). These frameworks have all identified food systems actions as powerful, particularly in their capacity to integrate across goals. Mobilising and repurposing finance is essential for enabling this transformation

01201-2/asset/7eef048f-a528-4f77-9cbf-54a32069a36c/main.assets/gr1_lrg.jpg)

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0