Strength in unity: How universities and government can address the regional healthcare crisis – Charles Sturt University

Report on Regional Healthcare Disparities and Educational Solutions in Australia

Executive Summary: Addressing Inequalities for Sustainable Development

A significant crisis in regional Australian healthcare presents an opportunity for systemic change through strategic partnerships. The disparity in healthcare access and outcomes between urban and regional areas directly contravenes the principles of several Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being) and SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities). This report outlines the current challenges and proposes that targeted investment in regional education, facilitated by government and university collaboration (SDG 17), is the primary solution to ensure equitable healthcare access and build sustainable regional communities (SDG 11).

Analysis of Regional Health Inequities: A Challenge to SDG 3 and SDG 10

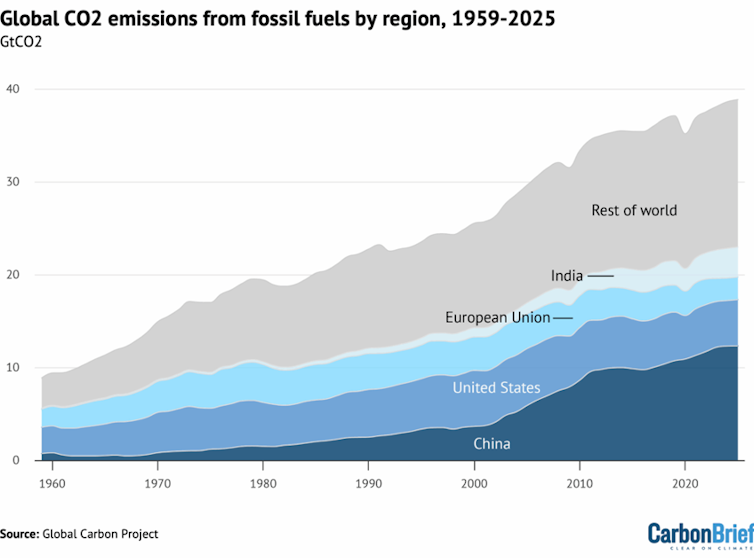

The healthcare gap between urban and regional Australia results in severe consequences, fundamentally undermining the goal of ensuring healthy lives and promoting well-being for all (SDG 3). Data from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare highlights a critical failure to reduce inequalities (SDG 10) within the nation.

- Poorer Health Outcomes: Regional populations suffer from higher rates of preventable hospitalisations compared to their urban counterparts.

- Reduced Life Expectancy: A stark indicator of this disparity is the significantly lower life expectancy in remote areas, with men living approximately seven years less and women six years less than those in major cities.

- Scarcity of General Practitioners (GPs): The most evident challenge is the shortage of GPs, leading to extensive waiting lists and inadequate access to primary care, including essential services like obstetrics.

The Role of Regional Education in Achieving SDG 4 and SDG 10

Investing in quality education (SDG 4) within regional areas is a proven strategy to address the healthcare workforce shortage and reduce health inequalities (SDG 10). Universities located in these regions are uniquely positioned to train and retain skilled professionals who are committed to serving their local communities.

A key initiative is the Joint Program in Medicine by Charles Sturt University and Western Sydney University. This program is designed to produce medical graduates who will practice in regional Australia, directly addressing the workforce deficit.

- Targeted Training: The program recruits students from regional backgrounds with the explicit goal of them serving regional communities post-graduation.

- High Retention Rates: Over 70 per cent of Charles Sturt University’s graduates remain to live and work in regional Australia, demonstrating the effectiveness of regional training models.

Strategic Partnerships for the Goals (SDG 17): A Call for Government and University Collaboration

To effectively scale these educational solutions, a robust partnership between government and universities is essential, aligning with SDG 17 (Partnerships for the Goals). While historical disagreements on funding models have existed, there is a shared objective to increase the number of frontline health workers in regional areas.

A critical opportunity lies in the allocation of new Commonwealth Supported Places (CSPs) for medical students. To maximize impact on regional health outcomes, these places must be directed to institutions with a proven track record of training doctors for regional practice.

- Allocation of CSPs: A reasonable share of the 100 new CSPs announced for 2026 should be allocated to Charles Sturt University to expand its successful regional medical program.

- Expanded Funding Models: Further investment is required to increase student capacity in other critical health fields, including nursing, midwifery, paramedicine, dentistry, and allied health.

Conclusion: Building a Sustainable and Equitable Healthcare Workforce

To ensure the development of sustainable communities (SDG 11) where all citizens have access to quality healthcare, it is imperative to address the current crisis. The government’s stated goal of delivering more doctors to every corner of the country can be realized by investing in proven regional education pathways. By strengthening the partnership between government and regional universities, Australia can build the necessary healthcare workforce to eliminate disparities, achieve SDG 3 and SDG 10, and ensure that a person’s postcode does not determine their health outcome.

Analysis of Sustainable Development Goals in the Article

1. Which SDGs are addressed or connected to the issues highlighted in the article?

The article highlights several issues that directly connect to the following Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs):

- SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being: The core theme of the article is the health crisis in regional Australia, focusing on disparities in health outcomes, access to healthcare professionals, and life expectancy. It directly addresses the goal of ensuring healthy lives and promoting well-being for all.

- SDG 4: Quality Education: The article proposes a solution to the healthcare crisis centered on education. It emphasizes the role of universities in training more doctors and health workers specifically for regional areas, linking directly to goals around accessible and quality tertiary education.

- SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities: The article is framed around the “city-country healthcare disparity.” It explicitly discusses the inequality in health services and outcomes based on geographic location (“postcode”), which is a key concern of SDG 10.

2. What specific targets under those SDGs can be identified based on the article’s content?

Based on the article’s discussion, the following specific SDG targets can be identified:

-

Under SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being):

- Target 3.8: “Achieve universal health coverage, including… access to quality essential health-care services…” The article highlights the failure to meet this target in regional Australia, citing the “scarcity of GPs,” long waiting lists (“at least 100 people”), and the inability for residents to access a doctor.

- Target 3.c: “Substantially increase health financing and the recruitment, development, training and retention of the health workforce…” The entire article is a call to action to address this target by training more doctors, nurses, midwives, and allied health students who will practice in regional Australia. The mention of Charles Sturt University’s medical program and the need for more Commonwealth Supported Places (CSPs) directly relates to increasing the health workforce in underserved areas.

-

Under SDG 4 (Quality Education):

- Target 4.3: “By 2030, ensure equal access for all women and men to affordable and quality technical, vocational and tertiary education, including university.” The article advocates for increasing the number of “Commonwealth Supported Places (CSPs) for medicine students” at regional universities. This is a direct effort to expand access to quality tertiary education for students in regional areas, enabling them to become healthcare professionals.

-

Under SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities):

- Target 10.2: “By 2030, empower and promote the social… inclusion of all, irrespective of… other status.” In this context, the “other status” is geographic location. The article’s goal to “ensure that every Australian—regardless of postcode—has access to the skilled professionals they need” is a direct call to reduce the inequality in health access and outcomes between urban and regional populations.

3. Are there any indicators mentioned or implied in the article that can be used to measure progress towards the identified targets?

Yes, the article mentions or implies several quantitative and qualitative indicators that can be used to measure progress:

- Life Expectancy Gap: The article states that “life expectancy is some seven years shorter for men and six years shorter for women in remote areas compared to their urban counterparts.” Reducing this gap is a clear indicator of progress towards SDG 3 and SDG 10.

- Rates of Preventable Hospitalisations: The mention of “higher rates of preventable hospitalisations” in regional Australia serves as a key health indicator. A reduction in these rates would signify improved primary healthcare access.

- Health Workforce Density: The “scarcity of GPs” and a “waiting list of at least 100 people” are indicators of low health workforce density. Progress could be measured by an increase in the number of GPs per capita in regional areas and a reduction in waiting times.

- Number of Medical Graduates for Regional Areas: The article mentions the “first graduating class of less than 40 medicine students” from a regional program. An increase in this number would be a direct indicator of progress towards Target 3.c.

- Number of Supported University Placements: The call for a “reasonable share of the 100 new Commonwealth Supported Places (CSPs)” provides a specific metric for measuring investment in regional medical education (Target 4.3).

- Graduate Retention Rates in Regional Areas: The statistic that “More than 70 per cent of Charles Sturt’s graduates go on to live and work in regional Australia” is a crucial indicator for measuring the success of regional training programs in retaining a local health workforce (Target 3.c).

4. Table of SDGs, Targets, and Indicators

| SDGs | Targets | Indicators Identified in the Article |

|---|---|---|

| SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being |

3.8: Achieve universal health coverage and access to quality essential health-care services.

3.c: Substantially increase the training and retention of the health workforce. |

|

| SDG 4: Quality Education | 4.3: Ensure equal access to affordable and quality tertiary education. |

|

| SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities | 10.2: Promote the inclusion of all, irrespective of location. |

|

Source: news.csu.edu.au

What is Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0