Ecuador Votes to Ban Oil Extraction in the Amazon

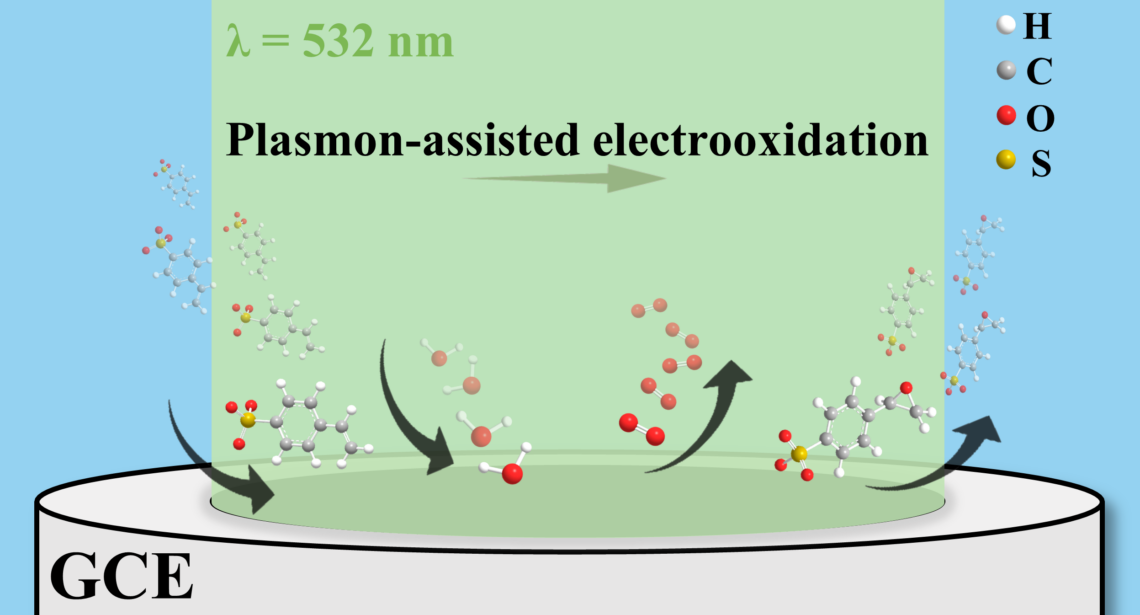

Ecuador is holding a historic referendum in which its citizens will decide the fate of oil extraction in the Yasuní National Park, one of the world's most biodiverse regions. The park, home to uncontacted indigenous communities and numerous species, contains Ecuador's largest crude oil reserve. The battle over this issue has been ongoing for a decade, with former President Rafael Correa initially proposing international funding to leave Yasuní undisturbed. However, drilling began in 2016, contributing significantly to Ecuador's oil production. The referendum has economic and environmental implications, with proponents of continued drilling arguing for employment opportunities, while "yes" campaigners suggest alternatives like eco-tourism, public transport electrification, and ending tax exemptions.

The people of Ecuador are heading to the polls – but they’re voting for more than just a new president. For the first time in history, the people will decide the fate of oil extraction in the Ecuadorian Amazon.

The referendum will give voters the chance to decide whether oil companies can continue to drill in one of the most biodiverse places on the planet, the Yasuní National Park, home to the last uncontacted indigenous communities in Ecuador.

The park encompasses around one million hectares at the meeting point of the Amazon, the Andes and the Equator. Just one hectare of Yasuní land supposedly contains more animal species than the whole of Europe and more tree species than exist in all of North America.

But underneath the land lies Ecuador’s largest reserve of crude oil.

“We are leading the world in tackling climate change by bypassing politicians and democratizing environmental decisions,” said Pedro Bermo, the spokesman for Yasunidos, an environmental collective who pushed for the referendum.

It’s been a decade-long battle that began when former President Rafael Correa boldly proposed that the international community give Ecuador $3.6 billion to leave Yasuní undisturbed. But the world wasn’t as generous as Correa expected. In 2016, the Ecuadorian state oil company began drilling in Block 43 – around 0.01% of the National Park – which today produces more than 55,000 barrels a day, amounting to around 12% of Ecuador’s oil production.

A continuous crusade of relentless campaigning and a successful petition eventually made its mark – in May, the country’s constitutional court authorized the vote to be included on the ballot of the upcoming election.

It’s a decision that will likely be instrumental to the future of Ecuador’s economy. Supporters who want to continue drilling believe the loss of employment opportunities would be disastrous.

“The backers of the request for crude to remain underground made it ten years ago when there wasn’t anything. 10 years later we find ourselves with 55,000 barrels per day, that’s 20 million barrels per year,” Energy Minister Fernando Santos told local radio.

“At $60 a barrel that’s $1.2 billion,” he added. “It could cause huge damage to the country,” he said, referring to economic damage and denying there has been environmental harm.

Alberto Acosta-Burneo, an economist and editor of the Weekly Analysis bulletin, said Ecuador would be “shooting itself in the foot” if it shut down drilling. In a video posted on X, formerly known as Twitter, he said that without cutting consumption all it would mean is another country selling Ecuador fuel.

“This election has two faces,” explained Bermo.

“On one hand we have the violence, the candidates, parties, and the same political mafias that governed Ecuador without significant changes.

“On the other hand, the referendum is the contrary – a citizen campaign full of hope, joy, art, activism and a lot of collective work to save this place. We are very optimistic.”

Among those campaigning to stop the drilling is Helena Gualinga, an indigenous rights advocate who hails from a remote village in the Ecuadorian Amazon – home of the Kichwa Sarayaku community.

ditor of the Weekly Analysis bulletin, said Ecuador would be “shooting itself in the foot” if it shut down drilling. In a video posted on X, formerly known as Twitter, he said that without cutting consumption all it would mean is another country selling Ecuador fuel.

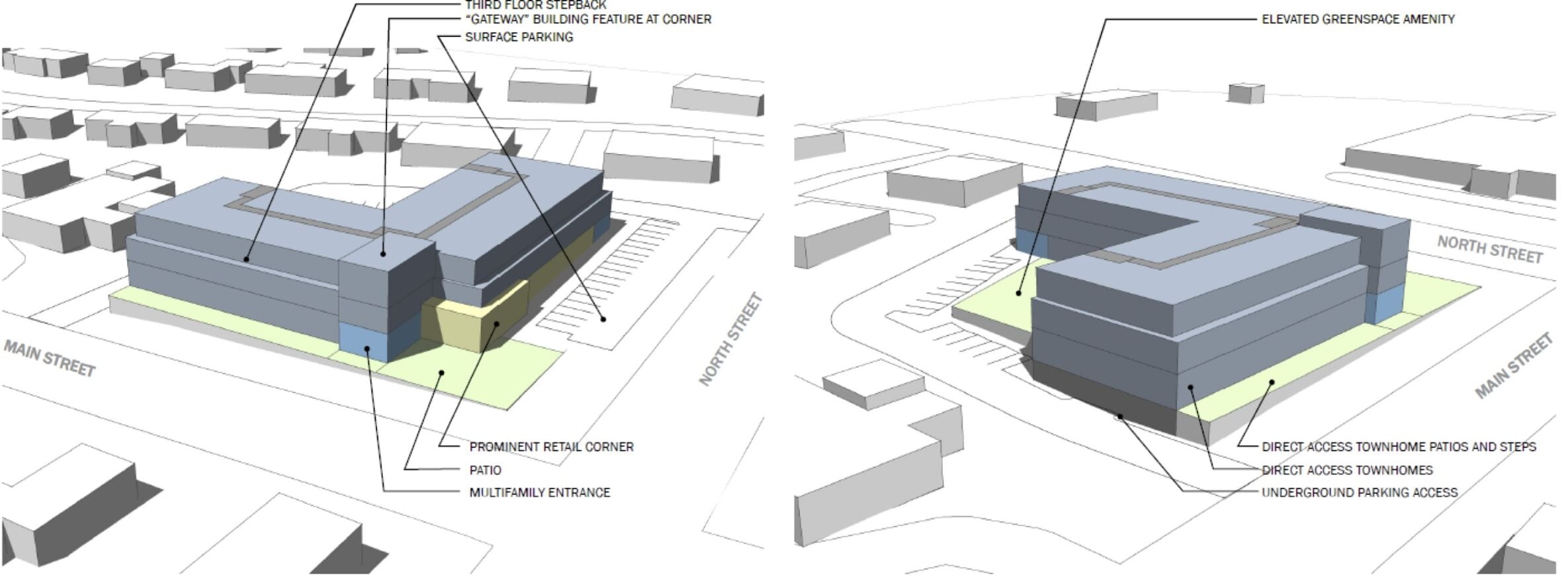

But ‘yes’ campaigners have ideas to fill the gap, from the promotion of eco-tourism and the electrification of public transport to eliminating tax exemptions. They claim that cutting the subsidies to the richest 10% of the country would generate four times more than what is obtained extracting oil from Yasuní.

“This referendum presents a huge opportunity for us to create change in a tangible way,” she told CNN.

For Gualinga, the most crucial part of the referendum is that if Yasunidos wins, the state oil company will have a one-year deadline to wrap up its operations in Block 43.

She explained that some oil companies have left areas in the Amazon without properly shutting down operations and restoring the area.

“This sentence would mean they have to do that.”

Those who wish to continue drilling in the area argue that meeting the one-year deadline to dismantle operations would be impossible.

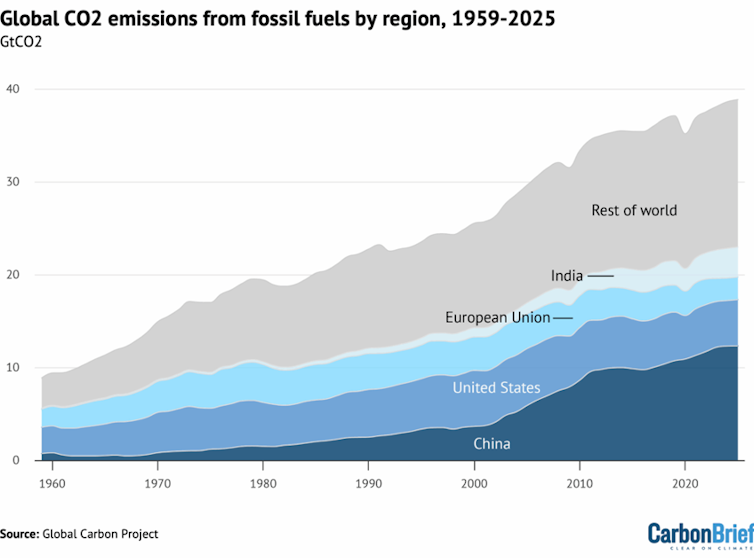

The referendum comes as the world faces blistering temperatures, with scientists declaring July as the hottest month on record, and the Amazon approaching what studies are suggesting is a critical tipping point that could have severe implications in the fight to tackle climate change.

And according to Antonia Juhasz, a Senior Researcher on Fossil Fuels at Human Rights Watch, it’s time for Ecuador to transition to a post-oil era. Ecuador’s GDP from oil has dropped significantly from around 18% in 2008, to just over 6% in 2021.

She believes the benefits of protecting the Amazon outweigh the benefits of maintaining dependence on oil, particularly considering the cost of regular oil spills and the consequences of worsening the climate crisis.

“The Amazon is worth more intact than in pieces, as are its people,” she said.

What is Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0