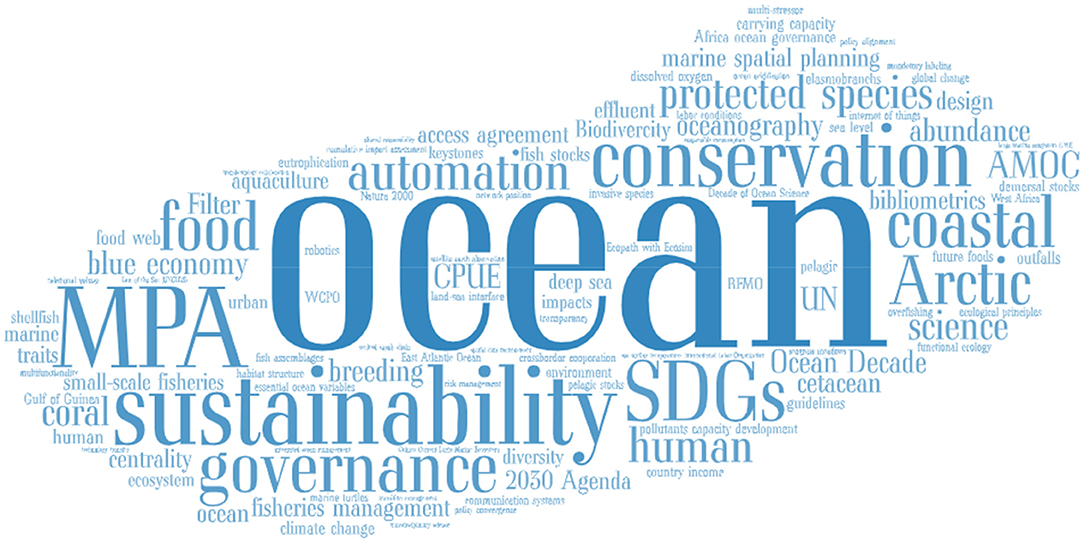

Editorial: Sustainable Development Goal 14 - Life Below Water: Towards a Sustainable Ocean

The editorial discusses the challenges and importance of achieving United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 14 – Life Below Water, emphasizing its vast scale and interconnectedness with other goals. The article highlights the need for sustainable practices below water to address global challenges such as poverty, hunger, and climate change. Despite significant gaps in understanding the ocean, the launch of the UN Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development aims to catalyze global efforts. Human activities, including fishing, shipping, plastic pollution, and climate change, leave measurable footprints, impacting marine ecosystems and services. The article explores solutions and initiatives focused on sustainable fishing, aquaculture, conservation planning, and the integration of cultural and spiritual values. It addresses future risks, climate change impacts, and the role of technology in monitoring and promoting ocean sustainability. The social dimension is deemed critical for engaging stakeholders and developing effective governance policies. The editorial acknowledges the research topic's contribution to diverse approaches and intellectual capital invested in ocean sustainability, supporting not only SDG 14 but also other interconnected goals. The hope is for ongoing initiatives to facilitate synergies and transdisciplinary approaches for comprehensive policy development in the UN Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development.

United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 14 – Life Below Water – is arguably one of the most challenging of the 17 goals (United Nations, 2016) due to the immense scale of the Ocean (almost three-quarters of the planet's surface) and the direct links to many other SDGs. For example, No Poverty (SDG 1), Zero Hunger (SDG2) and Good Health and Well-Being (SDG 3) all rely on sustainable Life Below Water (SDG 14). In turn, Climate Action (SDG 13) is needed to achieve SDG 14, and the Ocean is essential in achieving SDG 13. There is much that we still do not know; indeed, the Ocean represents more than 99% of the space where organisms can live, yet more than 80% of the Ocean remains unexplored, especially the deep-sea.

The launch of the UN Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development (2021–2030) aims at catalyzing a global focus to advance SDG 14 (Borja et al., 2020a). This will enhance the co-design of knowledge and actions for transformative ocean solutions, to address the challenges of a growing human population and climate change. Human pressures on the Ocean are important – 37% of the human population live in the coast from small villages to megacities exceeding 10 million people (e.g., New York, Shanghai, Lagos) and use the Ocean for a huge range of inputs, outputs and services, including amenity, food, transport, cooling water and waste disposal, as well as traditional and cultural uses. Many of these ecosystem services are undervalued, being conservatively estimated at $12.6 Trillion annually more than 20 years ago (Costanza et al., 1997). This is without considering two of the most severely undervalued services provided by the Ocean, as heat and carbon sinks, that have buffered many of the negative impacts of climate change. Many anthropogenic activities are leaving significant, direct and measurable global footprints in the Ocean with high profile examples including fishing1,2,3,, shipping lanes (Liu et al., 2019; Pirotta et al., 2019), dredging4, plastic pollution (Hardesty et al., 2017; Barrett et al., 2020), noise pollution (Di Franco et al., 2020; Chahouri et al., 2021; Duarte et al., 2021), and changes in Ocean chemistry5.

Human populations rely directly on the Ocean for food and other commercial activities, but a growing body of research has identified our dependency on the Ocean for health and well-being (Borja et al., 2020b). Other ecosystem services provided by the Ocean are also yet to be properly considered. These include the cultural and spiritual services provided by the Ocean (Brown and Hausner, 2017; de Juan et al., 2021), which have developed over millennia of human relationships with the Ocean and represent knowledge and connections that extend beyond monetary value. Aiming to integrate this knowledge in scientific endeavours, many indigenous peoples are bringing their traditional science and knowledge to partner with western science (Mazzocchi, 2006) and provide a more in-depth and long-term understanding of the Ocean, especially in coastal areas (Mustonen et al., 2021).

While the challenges are clear and sometimes seem overwhelming, approaches and solutions are being actively developed and tested; several of these are explored in this Research Topic.

With more than three billion people who rely on fish for at least 20% of their daily protein, and more than 120 million directly employed in the fishing and aquaculture sectors6, sustainable fishing (Penca; Fiorentino and Vitale; Jaiteh et al.) and aquaculture (Azra et al.) were a natural focus of several papers. This included a call for reducing effort in mixed species fisheries, and therefore fishing mortality, to take into account the differing and lower productivity of some species and the risk to their sustainability (Newman et al., 2018), and adopt a quota system based on “pretty good yield” (Hilborn, 2010).

Others emphasized the need for better conservation planning and coordination (Katsanevakis et al.; Ceccarelli et al.; Herrera et al.) as well as integration of their cultural and spiritual values into wider society (Baker et al.). This includes the need to improve spatial management, providing specific approaches to minimize human impacts and risks to charismatic megafauna. This management approach could be applied to whale watching activities, to support sustainable non-extractive human activities in the Ocean (Almunia et al.). The article by Adewumi et al., dealing with the Guinea Current Large Marine Ecosystem shared among Benin, Nigeria, and Cameroon, highlighted the challenges of international ocean governance, a result of political characteristics, the relics of colonialism, and increasing ocean use and pressure on marine ecosystems and services. The administrative and political arrangements differ significantly among countries, complicating transnational collaboration. The review of these arrangements revealed varying levels of convergence at international, regional and national levels, and could be a model to assist regional fishery management organizations to support positive steps toward ocean sustainability (Juan-Jordá et al., 2018).

Future risks to the Ocean (Garcia-Soto et al.), including those imposed by climate change (Green et al.), and the tools (Mariani et al.), approaches (e.g., Endrédi et al.; Hsu et al.), and ways to monitor this complex system (Jones et al.), including biodiversity (Herrera et al.), highlighted the extraordinary and diverse values of the Ocean and challenges (Figure 1). Embracing modern technologies (Almunia et al.; Green et al.), including the Internet of Things (Mariani et al.), could also promote and support a harmonization of ocean monitoring among all nations, and support international initiatives and cooperation7, including platforms to involve the wider community8.

The social dimension (Haward and Haas) will also be critical as a way of valuing and engaging with direct and indirect stakeholders of the Ocean and in developing better policies for governance (Paredes-Coral et al.; Polejack; Adewumi et al.; Kirkfeldt and Frazão Santos; Archana and Baker; Rohmana et al.). This is especially true at the land-sea interface (Singh et al.) where human populations concentrate and the risks from a changing climate are directly evident, with projected sea level rise (Nicholls and Cazenave, 2010; Hooijer and Vernimmen, 2021), and more frequent and intense storms (Pugatch, 2019; Chen et al., 2020). It is also true for the deep ocean (Howell et al.), which remains largely unexplored. The socio-ecological connections described in this Research Topic of Frontiers in Marine Science provide frameworks and hope for a sustainable future for the coasts and ocean.

While this Frontiers in Marine Science Research Topic does not represent all initiatives underway globally to address SDG 14, it provides a glimpse of some of the diverse approaches and intellectual capital invested in ocean sustainability. While the goal focuses on Life Below Water, these approaches directly support many other SDGs, which arguably cannot be achieved without a healthy and sustainable ocean (Mustonen et al., 2021).

We hope that other initiatives currently underway will assist in not only highlighting the links between SDG 14 and other SDGs but also provide a way for synergies among disparate knowledge domains to support transdisciplinary and multi-sectoral approaches for good policy development. As examples, we note the significant initiatives around the globe in areas of blue carbon and an equitable “blue economy.” Blue carbon projects not only protect and restore seagrass, mangrove, salt marsh, and macrophytes, but also support the associated biodiversity and human livelihoods that depend on these critical habitat-forming species. “Working with nature approaches” including in the restoration of corals, seagrasses, seaweeds, and mangroves are underway around the globe, with new methods being developed and tested [e.g., genetic techniques to identify more heat tolerant species of coral (Buerger et al., 2020) and other marine habitat building species (Alsuwaiyan et al., 2021)].

The efforts in these areas will be underpinned by new methods of accounting—such as blue carbon, biodiversity, ecosystem services and a framework of ocean accounting which is currently being developed9. This approach embraces environmental, social and cultural accounting, in addition to economic accounting, to better assess and value entire marine areas and ecosystems and integrate a wide range of SDGs. Our hope is that this will support and enable clearer and better decisions by ocean and coastal management agencies. These decisions should be based on a number of decision support tools, including: (i) management strategy evaluation approaches, (ii) scenario testing including assessing a range of alternative approaches, and (iii) potentially creating digital twins to test and explore management decisions before ocean activities commence.

We look forward to making the difficult possible and contributing to a vibrant, thriving future throughout the UN Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development and the UN Decade of Restoration (Waltham et al., 2020) based on some of the cutting-edge approaches detailed in this Research Topic of Frontiers in Marine Science.

Footnotes

1. ^https://globalfishingwatch.org/.

2. ^http://www.seaaroundus.org/.

3. ^https://www.minderoo.org/global-fishing-index/.

4. ^https://wamsi.org.au/wp-content/uploads/bsk-pdf-manager/2019/10/Dredging-Science-Synthesis-Report-A-Synthesis-of-Research-2012-2018-April-2019.pdf.

5. ^https://www.science.org.au/curious/earth-environment/ocean-acidification.

6. ^https://www.fao.org/in-action/eaf-nansen/news-events/detail-events/en/c/1413988/.

7. ^https://www.geoaquawatch.org/.

What is Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0