Feminist Foreign Policies Are Fighting for Their Life – Ms. Magazine

Report on the Status of Feminist Foreign Policy and its Alignment with Sustainable Development Goals

Introduction: Global Challenges to Gender Equality and the 2030 Agenda

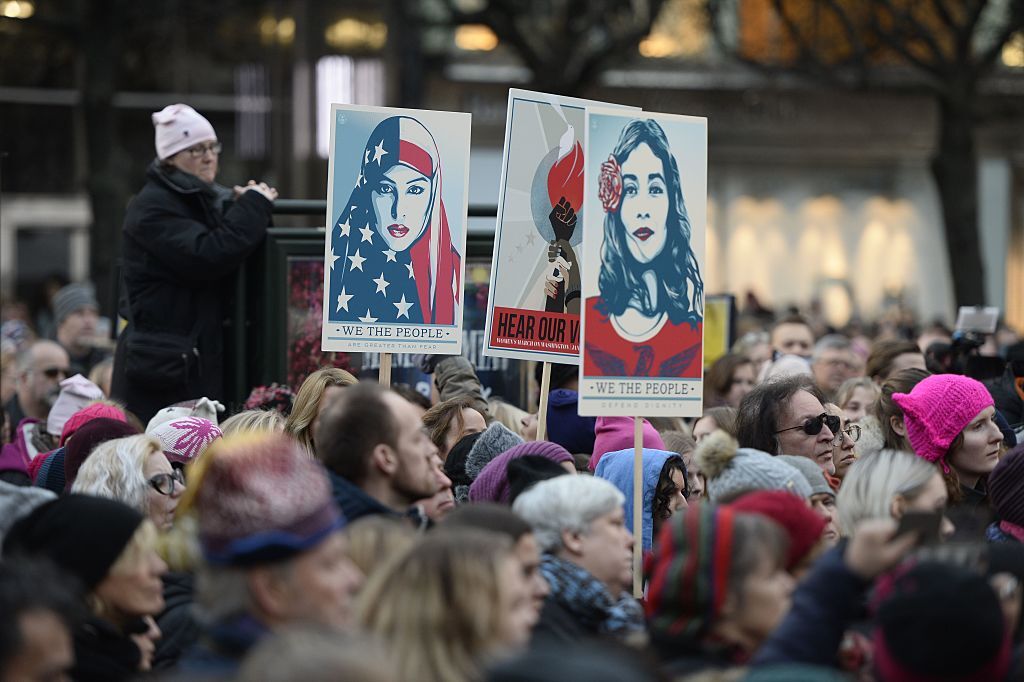

A recent ministerial conference in Paris highlighted a growing global conflict impacting the advancement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). While countries committed to Feminist Foreign Policy (FFP) continue to champion gender equality, they face significant opposition from well-financed anti-rights movements. This opposition directly threatens progress on key targets within the 2030 Agenda, particularly SDG 5 (Gender Equality), SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being), and SDG 16 (Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions).

Current Landscape of Feminist Foreign Policy Implementation

A comprehensive report by the Feminist Foreign Policy Collaborative details the current state of FFP, a policy framework that integrates a gender lens into foreign relations, linking peace, gender equality, and climate concerns. The status of FFP adoption is mixed:

- Setbacks: Several nations, including Sweden, Argentina, the Netherlands, and Germany, have recently renounced their formal FFP commitments.

- Resilience: Governments supportive of FFP have been retained in countries such as Slovenia, Spain, Liberia, France, Mexico, and Canada.

- Emerging Interest: A number of countries, including Australia, Brazil, Honduras, Nepal, and the United Kingdom, are actively exploring feminist approaches to their foreign policy.

Opposition to SDG 5 and SDG 3: The Attack on Sexual and Reproductive Health

The core of the opposition to FFP is a targeted attack on sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR), which are fundamental to achieving SDG 5 (Gender Equality) and SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being).

- Targeting Core SDG Principles: Anti-rights groups, supported by religious conservative forces, specifically target FFP’s emphasis on SRHR. This undermines progress towards SDG Target 5.6 (ensure universal access to sexual and reproductive health and reproductive rights) and SDG Target 3.7 (ensure universal access to sexual and reproductive health-care services).

- Influence in Global Forums: This pressure was evident at the recent UN Commission on the Status of Women, where the final declaration omitted references to SRHR. The opposition culminated in a denunciation of the declaration and the entire 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development by some member states.

- Commitment from FFP Nations: In response, FFP countries have reaffirmed their commitment to these principles. A cross-regional group of 78 nations has upheld investment in SRHR, and the Paris conference declaration was intentionally targeted in its language around bodily autonomy.

Financial Disparities and Implications for SDG 17 (Partnerships for the Goals)

The struggle to implement FFP and its associated SDGs is increasingly defined by a significant financial imbalance, impacting SDG 17 (Partnerships for the Goals).

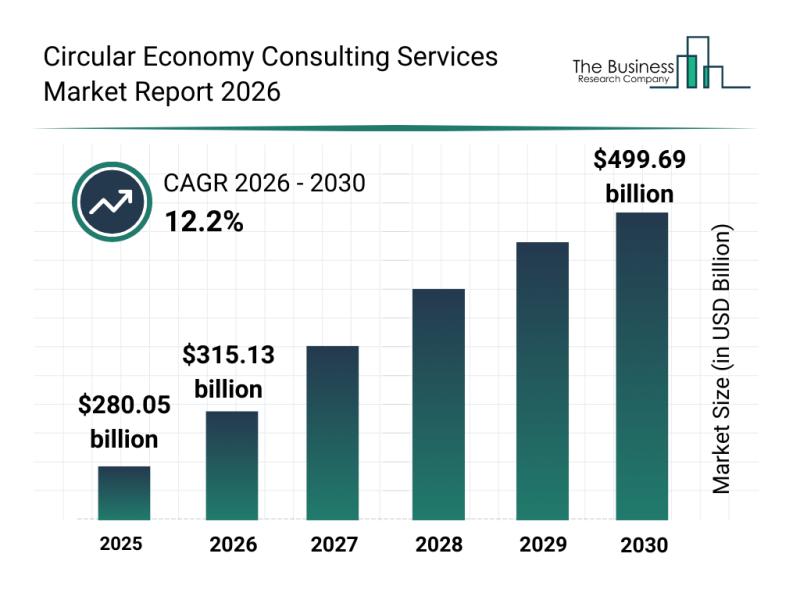

- Decline in Official Development Assistance (ODA): ODA, a critical funding mechanism for the SDGs, dropped by 9% in 2024, with further declines predicted. This threatens global partnerships and development programs.

- FFP Countries as Key Donors: Countries with feminist policies are, on average, higher ODA contributors than other members of the OECD’s Development Assistance Committee, making the attacks on their policies a threat to broader development funding.

- Surge in Anti-Rights Funding: Research indicates a decisive funding advantage for opposition movements, which have received approximately $1.2 billion in the past five years. This significantly outpaces the $700 million secured by pro-rights advocates over the last decade. These funds originate from sources in the United States, Europe, and Russia.

Outlook and Strategic Opportunities for the 2030 Agenda

Despite the considerable challenges, strategic opportunities exist to advance FFP and the gender equality agenda.

- Strengthening Alliances: The Paris conference declaration, signed by 31 governments, demonstrates a solidifying coalition of countries committed to upholding bodily autonomy and reproductive rights.

- Advocacy within Global Institutions: The presence of FFP champions France, Colombia, and Liberia as members of the UN Security Council in the coming year offers a significant platform. This provides a strategic window to integrate the principles of gender equality into global peace and security efforts, directly supporting the objectives of SDG 16 (Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions).

Analysis of Sustainable Development Goals in the Article

1. Which SDGs are addressed or connected to the issues highlighted in the article?

The article primarily addresses issues related to several Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), focusing on the advancement and subsequent challenges to feminist policies on a global scale. The most relevant SDGs are:

- SDG 5: Gender Equality: This is the central theme of the article. The entire discussion revolves around “feminist foreign policy,” “women’s rights,” “gender policies,” and the fight to preserve funding for these initiatives. The article explicitly details the struggle over “sexual and reproductive health rights” and “bodily autonomy,” which are core components of gender equality.

- SDG 17: Partnerships for the Goals: The article extensively discusses global partnerships, funding mechanisms, and international cooperation. It highlights the role of bilateral funding through “Official Development Assistance (ODA),” the financial contributions of countries with feminist foreign policies, and the mobilization of resources by both feminist groups and “well-funded anti-rights opposition movements.” The “Feminist Foreign Policy Collaborative” is described as a partnership across “government, civil society and philanthropy.”

- SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being: The article places a strong emphasis on health, specifically “sexual and reproductive health rights.” It notes that this issue is a primary target of opposition groups and a key value for countries with feminist foreign policies. The mention of the “Geneva Consensus Declaration,” which “attacks reproductive, abortion and LGBTQ+ rights,” directly connects the discussion to health outcomes and access to care.

- SDG 16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions: The article connects feminist foreign policy to institutional strength and peace. It defines the policy as linking “peace, gender equality and climate concerns.” Furthermore, it discusses the role of governmental bodies like “ministries of foreign affairs,” regional alliances, and international institutions like the “U.N. Security Council” in either advancing or hindering these policies. The struggle between pro- and anti-rights groups for influence over policy and legislation is a matter of institutional integrity and justice.

2. What specific targets under those SDGs can be identified based on the article’s content?

Based on the issues discussed, several specific SDG targets can be identified:

- Target 5.1: End all forms of discrimination against all women and girls everywhere. The article’s focus on the “global attack on sexual and reproductive health” and the efforts of “anti-rights groups” highlights the ongoing fight against discriminatory practices and policies that harm women and girls.

- Target 5.5: Ensure women’s full and effective participation and equal opportunities for leadership at all levels of decision-making in political, economic and public life. The article mentions that one of the advances in feminist foreign policy includes “achieving gender parity in ministries of foreign affairs and similar bodies,” which directly relates to this target.

- Target 5.6: Ensure universal access to sexual and reproductive health and reproductive rights. This is a central point of conflict described in the article. The push by feminist foreign policy countries to uphold “investment in sexual reproductive health and rights” and the opposition’s focus on attacking these rights directly align with this target. The Paris conference declaration’s “targeted language around families and bodily autonomy” is a clear example.

- Target 5.c: Adopt and strengthen sound policies and enforceable legislation for the promotion of gender equality and the empowerment of all women and girls at all levels. The entire concept of a “Feminist Foreign Policy (FFP)” is an embodiment of this target. The article tracks which countries adopt, renounce, or explore such policies (e.g., Sweden, Argentina, Australia, Brazil).

- Target 3.7: By 2030, ensure universal access to sexual and reproductive health-care services. The article’s repeated references to the battle over “sexual and reproductive health rights” and the funding for related programs directly correspond to this health-focused target.

- Target 17.2: Developed countries to implement fully their official development assistance commitments. The article directly discusses “Official Development Assistance, or ODA,” noting that it “dropped nine percent in 2024” and that FFP countries are “higher contributors on average” than other major donors in the OECD’s Development Assistance Committee.

- Target 17.3: Mobilize additional financial resources for developing countries from multiple sources. The article details a financial struggle, contrasting the funding for feminist causes with the resources mobilized by opponents. It quantifies this by stating anti-rights groups received “$1.2 billion in the past five years versus $700 million in the past decade” for pro-rights groups.

3. Are there any indicators mentioned or implied in the article that can be used to measure progress towards the identified targets?

Yes, the article mentions or implies several quantitative and qualitative indicators that can be used to measure progress:

- Indicator for Target 17.2: The article provides a direct quantitative indicator for Official Development Assistance (ODA) flows. It states that ODA “dropped nine percent in 2024, with an even sharper decline of 9 percent to 17 percent predicted for 2025.” This percentage change in ODA is a clear metric for tracking progress on development assistance commitments.

- Indicator for Target 17.3: The article provides specific financial figures that serve as an indicator of resource mobilization. It cites research showing that “anti-rights opposition groups receiving more money: $1.2 billion in the past five years versus $700 million in the past decade.” These figures measure the financial resources being mobilized by different actors.

- Indicator for Target 5.c: The number of countries that have formally adopted, are exploring, or have renounced a Feminist Foreign Policy serves as a clear indicator. The article tracks this by naming countries like Sweden, Argentina, the Netherlands, Germany, Chile, France, Colombia, Liberia, Australia, and Brazil in relation to their FFP status.

- Indicator for Target 5.6: The number of governments signing declarations that support or oppose sexual and reproductive health rights is an implied indicator. The article notes that the Paris declaration supporting these rights was “initially signed by 31 governments,” while a cross-regional group of “78 countries” has upheld investment in this area. This can be contrasted with the 39 countries that signed the opposing Geneva Consensus Declaration.

- Indicator for Target 5.5: While not providing a specific number, the article implies an indicator by mentioning the goal of “achieving gender parity in ministries of foreign affairs and similar bodies.” Progress could be measured by the proportion of women in leadership positions within these institutions in different countries.

4. Table of SDGs, Targets, and Indicators

| SDGs | Targets | Indicators Identified in the Article |

|---|---|---|

| SDG 5: Gender Equality |

5.5: Ensure women’s full and effective participation and equal opportunities for leadership.

5.6: Ensure universal access to sexual and reproductive health and reproductive rights. 5.c: Adopt and strengthen sound policies and legislation for gender equality. |

– Progress toward “achieving gender parity in ministries of foreign affairs.”

– Number of countries signing declarations supporting reproductive rights (e.g., “31 governments” signed the Paris declaration). – Number of countries that have adopted, are exploring, or have renounced a Feminist Foreign Policy. |

| SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being | 3.7: Ensure universal access to sexual and reproductive health-care services. | – Level of investment in sexual and reproductive health and rights, as upheld by a group of “78 countries.” |

| SDG 17: Partnerships for the Goals |

17.2: Developed countries to implement fully their official development assistance (ODA) commitments.

17.3: Mobilize additional financial resources from multiple sources. |

– Percentage change in Official Development Assistance (ODA), which “dropped nine percent in 2024.”

– Dollar amount of funding mobilized by different groups (e.g., “$1.2 billion in the past five years” for anti-rights groups). |

Source: msmagazine.com

What is Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0

;Resize=620#)