Cheaper Cars Pollute More Than Expensive Ones, Causing Emissions Inequality – Technology Networks

Report on Vehicle Emissions Inequality and Sustainable Development Goals

Introduction

A study conducted by the University of Birmingham and published in the Journal of Cleaner Production reveals a significant correlation between vehicle price and pollutant emissions, highlighting a form of environmental inequality. The research indicates that less expensive, often older vehicles contribute disproportionately to urban air pollution. This report analyzes these findings through the framework of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), demonstrating the interconnectedness of economic status, environmental quality, and public health.

Methodology and Key Findings

The research team employed advanced remote sensing technology and machine learning-based price estimation to analyze real-time emissions from over 50,000 vehicles. The study established a direct link between higher vehicle prices and lower emissions of key pollutants, including nitrogen oxides (NOx), nitrogen dioxide (NO₂), carbon monoxide (CO), and particulate matter (PM).

Key Findings

- Price and Emissions Correlation: Higher-priced vehicles were found to emit significantly fewer pollutants. For example, a diesel car valued at £5,000 emits approximately 8.8 g/litre of NOx, whereas a £15,000 car emits only 5.6 g/litre. An additional £10,000 spent on a diesel vehicle is associated with a more than 40% reduction in NOx emissions.

- Fuel Type Disparity: Diesel vehicles exhibit a more pronounced reduction in emissions per £1,000 increase in price compared to petrol vehicles. For every £1,000 increase in the price of a diesel car, NO₂ emissions decrease by approximately 0.4 g/litre of fuel.

- Vehicle Age Factor: The correlation between price and emissions is stronger in older vehicles. Older diesel models (Euro 5) show emission reductions 1.5 times steeper with price increases than newer Euro 6 models.

Implications for Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

The study’s findings have profound implications for several SDGs, revealing how economic disparities can impede progress towards a sustainable and equitable future.

- SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being: By demonstrating that cheaper vehicles are higher polluters, the study highlights a direct threat to urban public health. Increased local air pollution from these vehicles contributes to respiratory illnesses and other health issues, disproportionately affecting residents in lower-income areas and undermining the goal of ensuring healthy lives for all.

- SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities: The research uncovers a critical “emissions inequality.” Lower-income individuals, who are more likely to own older, cheaper vehicles, inadvertently contribute more to local air pollution. This creates a cycle where disadvantaged communities often bear the dual burden of causing and being most exposed to environmental hazards, directly contradicting the objective of reducing inequality within and among countries.

- SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities: The concentration of higher-emitting vehicles in certain urban areas compromises the goal of making cities inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable. Addressing this source of pollution is essential for improving urban air quality and creating healthier living environments for all residents.

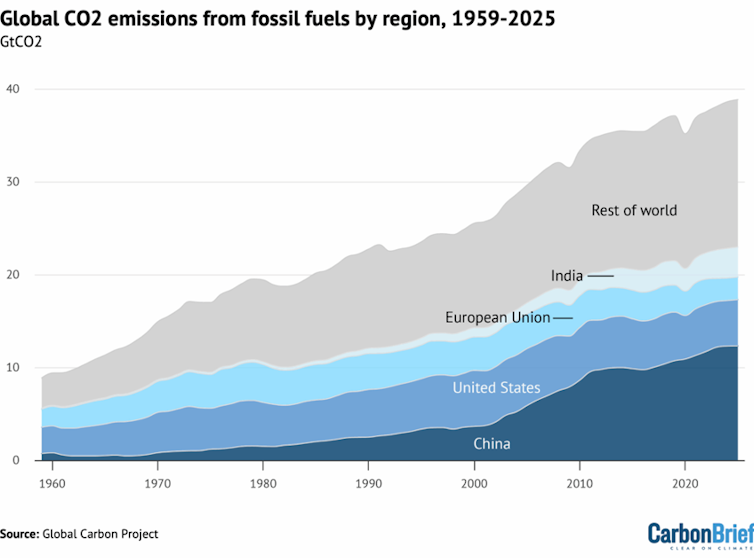

- SDG 13: Climate Action: While focused on local air pollutants, the issue of vehicle emissions is intrinsically linked to climate action. Promoting the transition to cleaner, more efficient vehicles is a key strategy for reducing the transport sector’s overall environmental footprint, which includes both air pollutants and greenhouse gases.

Policy Recommendations for Achieving SDGs

To address the environmental injustice highlighted in the report and advance the SDGs, the researchers propose several targeted policy interventions:

- Progressive Tax Structures: Implement tax systems based on both vehicle emissions and price. This would incentivize the adoption of cleaner vehicles and align with SDG 10 by ensuring that policies do not disproportionately burden lower-income households.

- Targeted Rebate and Scrappage Schemes: Introduce financial incentives, such as rebates or scrappage programs, specifically for lower-income households. This would accelerate the transition to cleaner transport, promoting a just transition and supporting progress on SDG 11 and SDG 13.

- Enhanced Vehicle Maintenance Programs: Strengthen inspection and maintenance requirements, particularly for older vehicles. This offers a cost-effective, short-term strategy to reduce emissions, directly contributing to improved urban air quality (SDG 3 and SDG 11).

Conclusion

The direct link between vehicle affordability and pollution levels underscores the necessity of integrating socioeconomic considerations into environmental and transport policy. To achieve the Sustainable Development Goals, particularly those related to health, equality, and sustainable cities, policymakers must address the root causes of emissions inequality. Future strategies must be designed to ensure that the transition to cleaner transportation is equitable and does not place an undue burden on the most vulnerable communities.

Analysis of Sustainable Development Goals in the Article

-

Which SDGs are addressed or connected to the issues highlighted in the article?

The article highlights issues of air pollution, health impacts, and social inequality, which directly connect to several Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The primary SDGs addressed are:

-

SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being

The article discusses urban air pollution caused by vehicle emissions, which has severe health consequences. It explicitly mentions that “air pollution in the West Midlands has caused up to 2,300 premature deaths each year,” directly linking the topic to public health and well-being.

-

SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities

This is a central theme of the article. It introduces the concept of “emissions inequality,” where “lower-income individuals are more likely to own cheaper, higher-emitting vehicles and, therefore, contribute disproportionately to their local urban air pollution.” The article calls for policy interventions to address this “environmental injustice.”

-

SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities

The research focuses on “local urban air quality problems” and the environmental impact of transportation within cities. The goal of reducing vehicle emissions is fundamental to making cities more sustainable, safer, and healthier environments for their inhabitants.

-

SDG 12: Responsible Consumption and Production

The article, published in the “Journal of Cleaner Production,” examines the production and consumption patterns of vehicles. It analyzes how different types of vehicles (cheaper vs. expensive, older vs. newer) have varying environmental impacts, and it proposes policies like “scrappage incentives” to shift consumption towards cleaner options.

-

-

What specific targets under those SDGs can be identified based on the article’s content?

Based on the issues discussed, several specific SDG targets can be identified:

-

Under SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being

- Target 3.9: By 2030, substantially reduce the number of deaths and illnesses from hazardous chemicals and air, water and soil pollution and contamination. The article’s focus on reducing harmful vehicle emissions (NOx, PM, CO) and its reference to “premature deaths” from air pollution directly align with this target.

-

Under SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities

- Target 10.2: By 2030, empower and promote the social, economic and political inclusion of all, irrespective of… economic or other status. The article addresses the economic dimension of this target by highlighting how lower-income groups are disproportionately linked to higher pollution, and it proposes “rebate schemes or scrappage incentives for lower-income households” to ensure a more equitable transition to cleaner transport.

- Target 10.3: Ensure equal opportunity and reduce inequalities of outcome… The article identifies an unequal outcome where lower-income communities “bear the brunt of local air pollution.” The proposed policy interventions aim to correct this imbalance and promote environmental justice.

-

Under SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities

- Target 11.6: By 2030, reduce the adverse per capita environmental impact of cities, including by paying special attention to air quality… The entire study is dedicated to measuring and finding solutions for urban air pollution from vehicles, which is the core focus of this target.

-

Under SDG 12: Responsible Consumption and Production

- Target 12.4: By 2020, achieve the environmentally sound management of chemicals and all wastes… and significantly reduce their release to air… to minimize their adverse impacts on human health and the environment. The article’s analysis of vehicle emissions (NOx, NO₂, CO, PM) is a direct examination of the release of chemicals into the air, and its recommendations aim to minimize these releases.

-

-

Are there any indicators mentioned or implied in the article that can be used to measure progress towards the identified targets?

Yes, the article mentions and implies several quantitative and qualitative indicators that can be used to measure progress:

-

Directly Mentioned Indicators:

- Levels of specific air pollutants: The study measures emissions of Nitrogen Oxide (NOx), Nitrogen Dioxide (NO₂), Carbon Monoxide (CO), and Particulate Matter (PM). It provides specific quantitative data, such as “Average NOx emissions are approximately 8.8 g/litre of diesel for £5,000 cars, compared with 5.6 g/litre for £15,000 cars.” These measurements directly correspond to SDG indicator 11.6.2 (Annual mean levels of fine particulate matter).

- Vehicle Price: The article uses vehicle price as a primary indicator and proxy for economic capacity and emission performance. The correlation between a £10,000 increase in price and a 40% reduction in NOx emissions is a key indicator from the study.

-

Implied Indicators:

- Mortality/Morbidity rates from air pollution: The mention of “2,300 premature deaths each year” implies that the number of deaths and illnesses attributed to air pollution is a key indicator of the problem’s severity, aligning with SDG indicator 3.9.1 (Mortality rate attributed to household and ambient air pollution).

- Implementation of targeted policies: The article’s policy recommendations can be used as indicators of progress. The existence and uptake of “Progressive tax structures,” “Rebate schemes or scrappage incentives for lower-income households,” and “Enhanced inspection and maintenance programmes” would serve as indicators of action towards achieving social equity and environmental goals.

- Vehicle Fleet Composition: The proportion of older, higher-emitting vehicles (e.g., Euro 5) versus newer, cleaner models (e.g., Euro 6) in a city’s fleet is an implied indicator of overall urban emission levels and the success of transition policies.

-

SDGs, Targets, and Indicators Summary

| SDGs | Targets | Indicators Identified in the Article |

|---|---|---|

| SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being | 3.9: Substantially reduce deaths and illnesses from air pollution. |

|

| SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities | 10.2: Promote social and economic inclusion. 10.3: Ensure equal opportunity and reduce inequalities of outcome. |

|

| SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities | 11.6: Reduce the adverse per capita environmental impact of cities, focusing on air quality. |

|

| SDG 12: Responsible Consumption and Production | 12.4: Achieve environmentally sound management of chemicals and reduce their release to air. |

|

Source: technologynetworks.com

What is Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0

;Resize=620#)