Mobilizing transport justice: a sufficientarian optimization framework for intermodal mobility systems – Nature

Executive Summary

This report analyzes the operational planning of transport systems through the lens of transport justice and its alignment with the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Traditional transport planning, which relies on utilitarian objectives like minimizing average travel time, often fails to address fairness and can exacerbate inequalities, undermining SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities) and SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities). This study bridges this gap by applying principles of justice to the operational planning of an intermodal Autonomous Mobility-on-Demand (I-AMoD) system. Using a real-world case study in Eindhoven, the Netherlands, we compare a conventional utilitarian model with three sufficientarian models focused on travel time and accessibility. The findings demonstrate that prioritizing sufficient levels of service can significantly enhance transport equity for users without private cars, directly contributing to more inclusive and sustainable urban environments. The results highlight that different justice principles lead to distinct planning outcomes, underscoring the necessity of integrating social justice frameworks into transport engineering to effectively achieve key SDGs.

Introduction: Aligning Urban Mobility with Sustainable Development Goals

The Challenge of Urban Transport Inequity

Urban transport systems are critical for economic and social development, yet they frequently perpetuate inequality and environmental degradation, posing significant challenges to achieving the SDGs. Inequitable access to transportation limits opportunities for employment, education, and healthcare, directly impacting SDG 1 (No Poverty), SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth), and SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities). Conventional transport planning often optimizes for average efficiency, which can neglect the needs of marginalized communities and those without access to private vehicles. This approach can lead to social exclusion and hinder progress towards SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities), which calls for inclusive and accessible urban environments for all.

A Technology-Driven Opportunity for Sustainable Mobility

The emergence of Autonomous Mobility-on-Demand (AMoD) systems presents an opportunity to redesign urban mobility to be more sustainable and equitable. However, technology alone is not a panacea. If driven by purely economic or utilitarian objectives, AMoD could worsen congestion, pollution, and social divides, as seen with earlier transportation network companies. To avoid this, this report proposes a framework for planning the operation of an I-AMoD system—where self-driving vehicles are integrated with public transit and active modes—with the explicit goal of advancing social justice and achieving the SDGs. The central research question is how to apply principles of justice to optimize transport operations to ensure fair and sufficient accessibility for all citizens.

Conceptual Framework: From Utilitarianism to Sufficientarian Justice for SDG Attainment

Traditional Utilitarian Planning and Its Limitations

The standard approach in transport planning is utilitarian, aiming to maximize aggregate benefits, typically by minimizing average travel time for the greatest number of people. While seemingly efficient, this method has significant shortcomings in the context of the SDGs.

- It fails to account for the distribution of benefits, potentially improving conditions for those already well-served while neglecting the most disadvantaged, thereby conflicting with SDG 10.

- It can lead to spatially concentrated services in high-demand areas, further marginalizing peripheral communities and undermining the goal of inclusive cities under SDG 11.

Sufficientarian Principles for Inclusive Transport (SDG 10 & 11)

As an alternative, this report explores sufficientarianism, a principle of justice focused on ensuring everyone attains a minimum, “sufficient” level of a particular good—in this case, mobility and accessibility. This approach directly aligns with the ethos of the SDGs to “leave no one behind.” By setting a threshold for what is considered an acceptable travel time or a sufficient number of reachable destinations, planning can be reoriented to prioritize those who fall below this standard. This ensures a baseline level of service that enables participation in society, contributing to SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being), SDG 8, and SDG 11.

Operational Models for Evaluation

This study defines and compares four distinct operational models for an I-AMoD system, each based on a different principle of justice:

- Utilitarian Efficiency: Aims to minimize the overall average travel time for the car-less population.

- Commute Sufficiency: Aims to minimize unacceptably long travel times on average across a bundle of recurring trips (e.g., daily commutes), ensuring the average commute time remains below a “reasonable” threshold.

- Trip Sufficiency: Aims to ensure that each individual trip, not just the average commute, remains below the defined travel time threshold.

- Accessibility Sufficiency: Aims to provide all users with access to a sufficient range of destinations within a reasonable time, directly addressing a person’s capability to participate in out-of-home activities.

Case Study Analysis: Eindhoven, Netherlands

Methodology and Data

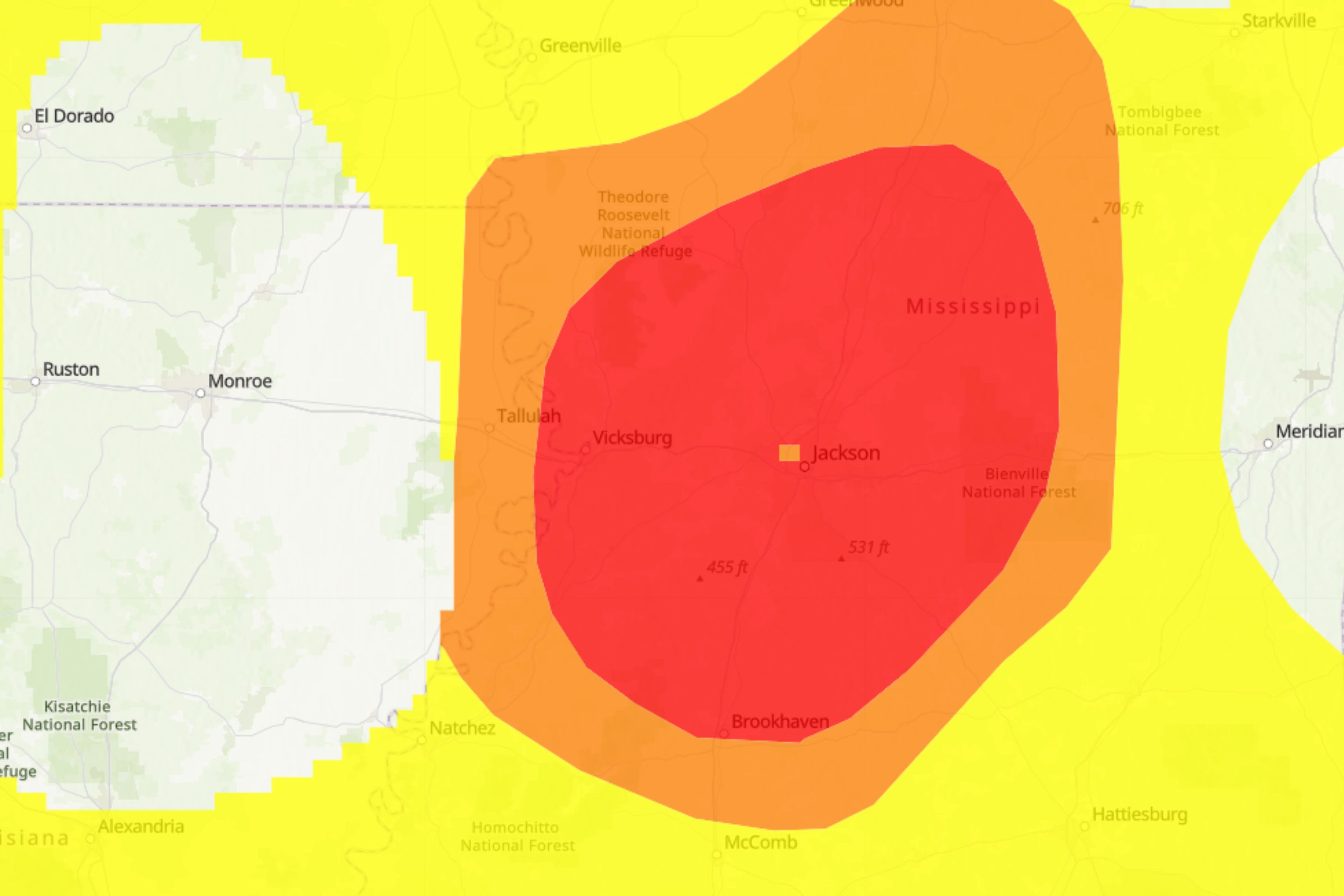

The analysis was conducted using a multi-layer network model of Eindhoven, Netherlands, incorporating road, bicycle, walking, and public transport networks. Realistic travel demand data was generated to simulate rush-hour conditions for the population segment without access to private cars. The operational planning for a fleet of 3,000 AMoD vehicles was optimized according to each of the four justice-based models. This approach provides a tangible evaluation of how different planning objectives can shape a city’s transport system and its contribution to SDG 11.

Comparative Analysis of Operational Models

- Utilitarian Efficiency vs. Commute Sufficiency: Optimizing for commute sufficiency significantly reduced the incidence of excessively long commutes by 87% compared to the utilitarian model. This substantial improvement in fairness and well-being (SDG 3, SDG 10) was achieved with less than a 1% increase in the overall average travel time, demonstrating that equity and efficiency are not mutually exclusive.

- Commute Sufficiency vs. Trip Sufficiency: The commute sufficiency model allows shorter trips to compensate for longer ones within a user’s travel pattern. In contrast, the trip sufficiency model prioritizes ensuring no single trip is unacceptably long. This latter approach provides a more consistent and reliable level of service, better aligning with the goal of universal access under SDG 11, though it results in a 9% increase in average travel time due to less efficient vehicle routing.

- Trip Sufficiency vs. Accessibility Sufficiency: The accessibility sufficiency model focuses on ensuring users can reach a minimum number of essential destinations within a reasonable time. This model directly targets a core component of social inclusion and economic opportunity (SDG 1, SDG 8, SDG 11). It improves regional accessibility deficits significantly but may permit some individual trips to non-essential, distant locations to remain very long, as resources are prioritized to guarantee a baseline level of opportunity for all.

Key Findings and Implications for Sustainable Urban Development

Summary of Performance Metrics

The case study reveals a clear trade-off between different justice principles. While the utilitarian model is most efficient in terms of average travel time, it performs poorly on equity measures. Sufficientarian models, particularly accessibility sufficiency, are far more effective at ensuring a baseline level of service for all, which is a cornerstone of sustainable and inclusive urban development.

Policy Implications for Achieving SDGs

- Planning Objectives Determine Equity Outcomes: The choice of optimization objective is not a neutral technical decision but a normative one with profound implications for social equity. To achieve SDG 10, transport planning must move beyond simple efficiency metrics.

- Sufficiency as a Tool for Inclusive Cities: A focus on sufficiency provides a practical framework for operationalizing the principles of SDG 11, ensuring that new mobility systems like AMoD serve the entire community, especially the most vulnerable.

- Informing Public Policy: This framework can be used by public authorities to analyze the trade-offs between different policy goals and to engage in a broader public debate about what constitutes a “sufficient” and “just” transportation system in the context of the SDGs.

Conclusion and Recommendations

This report demonstrates the critical importance of integrating principles of social justice into the operational planning of modern transport systems. By mobilizing concepts from transport justice, we have developed and tested a framework that allows for the optimization of mobility systems in alignment with the Sustainable Development Goals. The findings show that a shift from utilitarian efficiency to a sufficientarian approach can foster more equitable and inclusive urban mobility without significant sacrifices in overall system performance.

To advance this agenda, the following actions are recommended:

- Adopt a transdisciplinary approach to transport planning that embeds social science concepts of justice and equity into engineering and optimization models.

- Develop more sophisticated demand models that capture the latent travel needs of underserved populations, ensuring that future transport systems are designed for true accessibility and not just based on existing, potentially biased, travel patterns.

- Public authorities should lead a societal dialogue on defining sufficiency thresholds for accessibility, ensuring that transport planning is democratically informed and aligned with shared goals for sustainable and just communities (SDG 11).

Analysis of Sustainable Development Goals in the Article

1. Which SDGs are addressed or connected to the issues highlighted in the article?

- SDG 9: Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure

- The article focuses on applying technological advances, specifically “Autonomous Mobility-on-Demand (AMoD)” systems, to create a new form of transport infrastructure. It discusses the operational planning and optimization of these innovative systems to improve urban mobility.

- SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities

- A central theme of the article is “transport justice” and “social injustice.” The study explicitly aims to improve conditions for “users without access to private cars,” a segment of the population that often faces mobility disadvantages. By comparing different justice principles (utilitarianism vs. sufficientarianism), the article directly addresses how to reduce inequalities in accessibility.

- SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities

- The research is set within an urban context (Eindhoven, the Netherlands) and tackles core challenges of urban transport systems, including sustainability, accessibility, and social justice. The goal is to plan a transport system that makes the city more inclusive and sustainable for all its residents.

2. What specific targets under those SDGs can be identified based on the article’s content?

- Target 9.1: Develop quality, reliable, sustainable and resilient infrastructure… with a focus on affordable and equitable access for all.

- The article’s proposal to plan and optimize an “intermodal Autonomous Mobility-on-Demand system” directly relates to developing a new, technologically advanced transport infrastructure. The entire analysis is framed around ensuring this system provides equitable access, particularly for the “car-less population segment.”

- Target 10.2: By 2030, empower and promote the social, economic and political inclusion of all…

- The study’s focus on providing “sufficient level of accessibility” for all individuals, especially those without cars, is a direct effort to promote social and economic inclusion. The article states that the main goal of transport is to provide “the capability of reaching out-of-home activities,” which is fundamental for inclusion.

- Target 11.2: By 2030, provide access to safe, affordable, accessible and sustainable transport systems for all… with special attention to the needs of those in vulnerable situations.

- This target is the most directly addressed. The paper is entirely dedicated to creating a framework for planning transport systems that provide accessibility. It explicitly focuses on a vulnerable group (“individuals without cars”) and evaluates different strategies to ensure their transport needs are met in a just and sufficient manner.

- Target 11.6: By 2030, reduce the adverse per capita environmental impact of cities…

- Although not the primary focus, the introduction mentions that “environmental pollution” is a significant challenge for urban transport systems. The exploration of new mobility solutions like AMoD, which are often linked to electrification, implicitly connects to the goal of reducing the environmental impact of urban transport.

3. Are there any indicators mentioned or implied in the article that can be used to measure progress towards the identified targets?

The article does not use official UN indicators but proposes and analyzes several specific, quantifiable metrics to measure transport justice and accessibility, which serve as indicators for the identified targets.

- Average Travel Time

- This is used as the baseline metric for the “utilitarian efficiency” model. It measures the overall efficiency of the transport system by calculating the average time it takes for users to complete their trips.

- Commute Sufficiency

- This is a justice-based indicator defined as the minimization of “extra travel time above a specified travel time threshold” for users’ repeated commutes. It measures whether users, on average, have commute times that are considered “reasonable” or “acceptable.”

- Trip Sufficiency

- Similar to commute sufficiency, this indicator measures the extra travel time above a threshold, but it is applied to each individual trip rather than an average commute. This provides a more granular measure of whether single journeys meet a standard of sufficiency.

- Accessibility Sufficiency

- This indicator measures “the deficit in number of destinations reachable within a reasonable travel time with respect to a minimum threshold.” It directly quantifies a person’s ability to access a sufficient range of opportunities and activities, which is a core component of transport justice.

4. Summary Table of SDGs, Targets, and Indicators

| SDGs | Targets | Indicators |

|---|---|---|

| SDG 9: Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure | 9.1: Develop quality, reliable, sustainable and resilient infrastructure, including regional and transborder infrastructure, to support economic development and human well-being, with a focus on affordable and equitable access for all. |

|

| SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities | 10.2: By 2030, empower and promote the social, economic and political inclusion of all, irrespective of age, sex, disability, race, ethnicity, origin, religion or economic or other status. |

|

| SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities | 11.2: By 2030, provide access to safe, affordable, accessible and sustainable transport systems for all, improving road safety, notably by expanding public transport, with special attention to the needs of those in vulnerable situations… |

|

| SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities | 11.6: By 2030, reduce the adverse per capita environmental impact of cities, including by paying special attention to air quality and municipal and other waste management. |

|

Source: nature.com

What is Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0