Beyond Smart Cities: The Rise Of Regenerative Urbanism – Forbes

Report on the Transition from Smart Cities to Regenerative Urbanism in Alignment with Sustainable Development Goals

A new paradigm in urban development, termed “regenerative urbanism,” is emerging as a successor to the technology-focused “smart city” model. This report details the shift, analyzing how regenerative principles directly address the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by redefining value to encompass ecological restoration, social equity, and long-term resilience.

Limitations of the Smart City Model in Achieving SDG Targets

For two decades, the smart city model has prioritized data and technological optimization. However, research indicates this approach has had limited success in addressing complex urban challenges central to the SDGs.

- Social and Economic Inequity: Technology alone has not resolved systemic inequality, a key target of SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities) and SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities). A 2025 study in Nature Humanities and Social Sciences Communications on China’s smart-city policy noted mixed effects on livability and equity.

- Resource Scarcity and Environmental Impact: An exclusive focus on efficiency often fails to address the root causes of resource depletion and environmental degradation, undermining SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production) and SDG 13 (Climate Action).

- Fragmented Governance: The 2025 Urban Readiness Report highlights that city leaders are stretched between immediate needs and future-proofing, with infrastructure upgrades alone proving insufficient for sustainable urban living.

Regenerative Urbanism: A Holistic Framework for the 2030 Agenda

Regenerative urbanism moves beyond minimizing harm (sustainability) to actively restoring and enhancing urban ecosystems. This approach treats cities as living systems and provides a comprehensive framework for achieving multiple SDGs simultaneously.

Core Principles and SDG Alignment

- Ecological Restoration: The model prioritizes reversing environmental damage. With the built environment accounting for nearly 40% of global emissions, regenerative design is a direct strategy for SDG 13 (Climate Action) and restoring biodiversity aligns with SDG 15 (Life on Land).

- Social and Cultural Vitality: By focusing on community well-being, trust-building, and civic participation, the framework supports SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being) and the creation of inclusive public spaces as targeted by SDG 11.

- Economic Resilience: The approach fosters circular economies and long-term value creation, contributing to SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) and SDG 12.

The Regenerative Cities Manifesto: A Strategic Roadmap

Launched by the Future Food Institute and Tokyo Tatemono, the Regenerative Cities Manifesto provides a policy framework for integrating urban and rural systems. It is inspired by the FAO’s 1.5°C Roadmap, linking urban policy directly to global food security and climate goals.

Six Domains of Renewal for Integrated SDG Implementation

The Manifesto calls for renewal across six interconnected domains, breaking down the departmental silos that often hinder progress on the SDGs:

- Political

- Ecological

- Social

- Cultural

- Human

- Economic

This systemic approach is critical for advancing the interconnected nature of the 2030 Agenda, particularly through cross-sectoral collaboration as envisioned in SDG 17 (Partnerships for the Goals).

Implementation and Case Studies

The principles of regenerative urbanism are being implemented globally, demonstrating viable pathways for achieving SDG targets at the local level.

Tokyo’s Kyobashi Living Lab

A pilot project by Tokyo Tatemono and the Future Food Institute, the Living Lab uses food as a connector to test civic participation and build community resilience. This initiative directly advances:

- SDG 2 (Zero Hunger) by exploring sustainable urban food systems.

- SDG 11 by reimagining a business district as a living, community-focused ecosystem.

- SDG 17 through its partnership-based model for co-design and open data.

Global Best Practices

- Amsterdam and Portland: Over 50 local governments have joined the Doughnut Economics Action Lab, adapting circular principles that support SDG 12 into city-wide strategies.

- Milan: The city’s school-meal procurement program prioritizes local, circular food chains, advancing SDG 2 and SDG 12.

- Helsingborg: IKEA’s Do More project established a circular food ecosystem that employs marginalized women, contributing to SDG 5 (Gender Equality), SDG 8, and SDG 10.

- Lendlease and C40 Cities: These organizations are scaling regenerative design toolkits, restoring soil health and community cohesion while demonstrating the power of global networks under SDG 17.

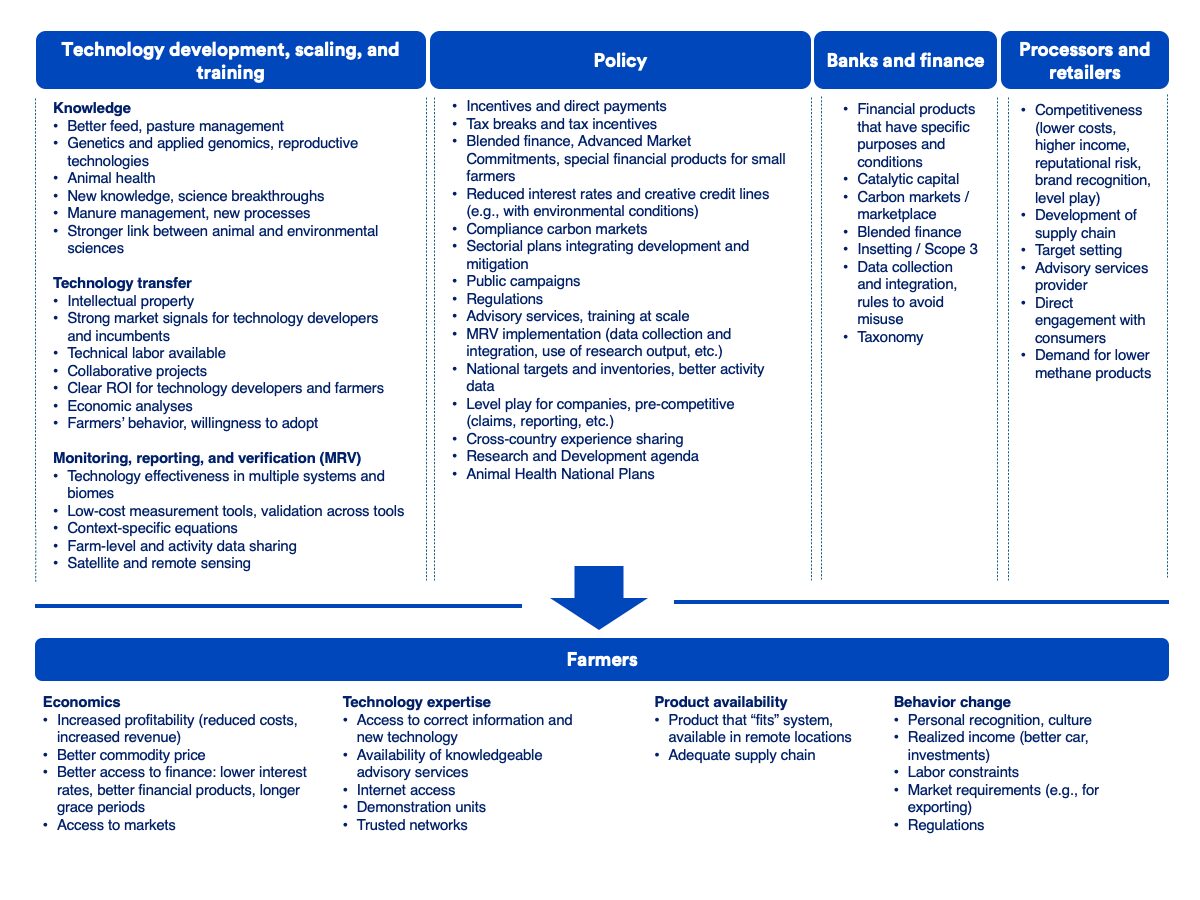

Financial Models for Regenerative Development

Regenerative urbanism is increasingly recognized as a sound investment strategy focused on long-term value. This shift aligns financial flows with sustainable development outcomes.

- Market Growth: The global urban-regeneration market is projected to reach $2.3 trillion by 2033, indicating that restorative, community-focused redevelopment is a major growth sector aligned with SDG 8.

- Sustainable Finance: The growth of sustainable finance instruments, such as green and social bonds totaling over $6 trillion globally, provides capital for projects that deliver measurable environmental and social returns, directly funding SDG-related infrastructure.

- Long-Term Value: Companies like Tokyo Tatemono are adopting century-scale investment horizons, prioritizing future social and cultural value over short-term profitability.

Conclusion: Scaling Regeneration Through Global Partnerships

The transition from smart cities to regenerative urbanism represents a fundamental shift toward a more holistic and effective model for sustainable urban development. By embedding the principles of ecological restoration, social equity, and circularity into its core, this new paradigm offers a practical framework for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. Success depends on scaling these practices through robust global partnerships, as emphasized by SDG 17, ensuring that cities can adapt and regenerate according to their unique cultural and ecological contexts, thereby creating conditions where both people and nature can flourish.

Analysis of the Article in Relation to Sustainable Development Goals

1. Which SDGs are addressed or connected to the issues highlighted in the article?

The article on regenerative urbanism connects to several Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by addressing the interconnected challenges of urban development, environmental degradation, and social well-being. The primary SDGs identified are:

- SDG 2: Zero Hunger: The article emphasizes food systems as a central component of regenerative cities, mentioning “regenerative agriculture,” “food sovereignty,” and creating “circular food ecosystem[s],” which are crucial for sustainable food production.

- SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth: The shift towards a regenerative model is presented as a new economic paradigm. The article highlights the “global urban-regeneration market at about $2.3 trillion by 2033” and projects that create employment for “marginalized women and local farmers,” linking regeneration to sustainable economic growth and job creation.

- SDG 9: Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure: The text discusses the need to “build or upgrade climate-resilient infrastructure” and criticizes the limits of purely technological solutions, advocating for innovative, resilient, and sustainable infrastructure development.

- SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities: This is the most central SDG in the article. The entire concept of “regenerative urbanism” is about transforming cities to improve “livability, resilience,” “rebuild communities,” and manage urban growth sustainably, directly addressing the core mission of SDG 11.

- SDG 12: Responsible Consumption and Production: The article promotes a shift from a linear to a circular model, mentioning “adapting circular and regenerative principles into city strategies” and developing “circular food chains,” which are key tenets of sustainable consumption and production.

- SDG 13: Climate Action: The article directly links urban development to climate change, stating that the “built environment accounts for nearly 40% of global emissions.” The call for “climate-resilient infrastructure” and reducing emissions through regenerative design is a core climate action strategy.

- SDG 15: Life on Land: The principle of regeneration is explicitly tied to ecological restoration. The article discusses the goal to “heal nature,” “reverse” damage, and focuses on “ecosystem restoration,” “biodiversity loss,” and restoring “soil health.”

- SDG 17: Partnerships for the Goals: The article repeatedly emphasizes the importance of collaboration. It highlights partnerships between the “Future Food Institute and Tokyo Tatemono,” the creation of “shared learning platforms” for stakeholders, and building “partnerships among cities, universities, and companies” as essential for achieving regenerative goals.

2. What specific targets under those SDGs can be identified based on the article’s content?

Based on the issues and solutions discussed, several specific SDG targets can be identified:

- Target 2.4: By 2030, ensure sustainable food production systems and implement resilient agricultural practices. The article’s focus on “regenerative agriculture,” “local, circular food chains” (as in Milan’s school-meal program), and “food sovereignty” directly supports this target.

- Target 9.1: Develop quality, reliable, sustainable and resilient infrastructure. The article highlights the need for “$4.5–5.4 trillion annually through 2030 to build or upgrade climate-resilient infrastructure,” which aligns perfectly with this target.

- Target 11.3: By 2030, enhance inclusive and sustainable urbanization and capacity for participatory, integrated and sustainable human settlement planning and management. The “Regenerative Cities Manifesto” and projects like the “Kyobashi Living Lab” that focus on “civic participation” and co-design are practical examples of implementing this target.

- Target 11.6: By 2030, reduce the adverse per capita environmental impact of cities. The article’s concern that the built environment accounts for “nearly 40% of global emissions” and the goal of regenerative design to “heal nature” directly address the need to reduce cities’ environmental footprint.

- Target 12.5: By 2030, substantially reduce waste generation through prevention, reduction, recycling and reuse. The adoption of “circular and regenerative principles” and the creation of a “circular food ecosystem” in Helsingborg are direct applications of this target.

- Target 13.1: Strengthen resilience and adaptive capacity to climate-related hazards and natural disasters in all countries. The entire paradigm of regenerative urbanism is framed around building “resilience” to “climate shocks” and other environmental pressures.

- Target 15.3: By 2030, combat desertification, restore degraded land and soil. The mention of projects that aim to “restore soil health” and reverse environmental damage through “ecosystem restoration” directly contributes to this target.

- Target 17.17: Encourage and promote effective public, public-private and civil society partnerships. The collaboration between Tokyo Tatemono (private sector) and the Future Food Institute (civil society), as well as multi-city networks like C40 Cities and the Doughnut Economics Action Lab, exemplify the multi-stakeholder partnerships needed to achieve the SDGs.

3. Are there any indicators mentioned or implied in the article that can be used to measure progress towards the identified targets?

The article mentions several quantitative and qualitative indicators that can be used to measure progress:

- Financial Investment in Resilience (Indicator for Target 9.1): The article quantifies the investment needed for climate-resilient infrastructure as “$4.5–5.4 trillion annually.” Tracking the flow of capital, including the “$6 trillion” in global sustainable-finance instruments, towards these projects serves as a key indicator.

- Greenhouse Gas Emissions from the Built Environment (Indicator for Target 11.6 & 13.2): The statistic that “the built environment accounts for nearly 40% of global emissions” establishes a baseline. A key indicator of progress would be the reduction of this percentage in cities adopting regenerative models.

- Market Growth of Regenerative Sector (Indicator for Target 8.2): The projection of the “global urban-regeneration market at about $2.3 trillion by 2033” is a direct economic indicator of the growth and adoption of these principles.

- Adoption by Municipalities (Indicator for Target 17.17): The article states that “More than 50 local governments have joined the Doughnut Economics Action Lab’s network.” The number of cities, organizations, and companies joining such collaborative networks is a measurable indicator of partnership and policy adoption.

- Restoration of Ecosystem Health (Implied Indicator for Target 15.3): While not quantified, the article implies progress can be measured by the health of urban ecosystems. Lendlease’s project to “restore soil health and community cohesion” suggests that indicators like soil quality, biodiversity levels, and green space coverage could be used.

- Local and Sustainable Procurement (Implied Indicator for Target 2.4 & 12.5): The example of “Milan’s school-meal procurement now favor[ing] local, circular food chains” implies an indicator: the percentage of public or private procurement that comes from local, regenerative, and circular sources.

4. Summary Table of SDGs, Targets, and Indicators

| SDGs | Targets | Indicators |

|---|---|---|

| SDG 2: Zero Hunger | 2.4: Ensure sustainable food production systems and implement resilient agricultural practices. | Percentage of public procurement from local and circular food chains (implied by Milan’s school-meal program). |

| SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth | 8.2: Achieve higher levels of economic productivity through diversification, technological upgrading and innovation. | Growth of the global urban-regeneration market (valued at $2.3 trillion by 2033). |

| SDG 9: Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure | 9.1: Develop quality, reliable, sustainable and resilient infrastructure. | Annual investment in climate-resilient infrastructure (target of $4.5–5.4 trillion annually). |

| SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities | 11.3: Enhance inclusive and sustainable urbanization and capacity for participatory planning. | Level of civic participation and trust-building in urban projects (e.g., Kyobashi Living Lab). |

| SDG 12: Responsible Consumption and Production | 12.5: Substantially reduce waste generation through prevention, reduction, recycling and reuse. | Adoption of circular economy principles in city strategies and projects (e.g., Helsingborg’s circular food ecosystem). |

| SDG 13: Climate Action | 13.1: Strengthen resilience and adaptive capacity to climate-related hazards. | Reduction in the percentage of global emissions from the built environment (baseline of nearly 40%). |

| SDG 15: Life on Land | 15.3: Combat desertification, restore degraded land and soil. | Metrics on soil health and ecosystem restoration in urban development projects (implied by Lendlease’s Milan project). |

| SDG 17: Partnerships for the Goals | 17.17: Encourage and promote effective public, public-private and civil society partnerships. | Number of local governments and organizations joining collaborative networks (e.g., “More than 50” in the Doughnut Economics Action Lab). |

Source: forbes.com

What is Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0