Experts say ultra-processed foods are a ‘major public health threat.’ Here’s how to protect yourself – The Globe and Mail

Report on the Impact of Ultra-Processed Foods on Sustainable Development Goals

Introduction: The Global Challenge of Ultra-Processed Foods (UPFs)

A recent series in The Lancet, authored by 43 international experts, identifies the global increase in the consumption of ultra-processed foods (UPFs) as a significant challenge to public health. This trend directly threatens the achievement of several Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly those related to health, nutrition, and sustainable consumption. UPFs are industrial formulations made from inexpensive ingredients and additives, designed to be hyper-palatable and aggressively marketed. Consumption is high in developed nations, accounting for 46% of calories in Canada and 55% in the U.S. and U.K., and is rising rapidly in lower-income countries, exacerbating global health inequities.

Alignment with SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being

The proliferation of UPFs is a direct impediment to SDG 3, which aims to ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all. The consumption of UPFs is linked to a decline in diet quality and a range of adverse health outcomes that undermine SDG Target 3.4, which seeks to reduce premature mortality from non-communicable diseases (NCDs).

- Nutrient Imbalances: UPF-heavy diets displace whole and minimally processed foods, leading to nutrient deficiencies and an increased intake of harmful additives.

- Physiological Damage: Scientific evidence associates UPF consumption with inflammation, elevated blood glucose, adverse cholesterol levels, and unfavourable microbiome alterations.

- Increased NCD Risk: Over 100 studies substantiate the hypothesis that high UPF intake increases the risk of multiple chronic diseases across nearly all organ systems. A recent study in JAMA Oncology specifically associated high UPF intake in women under 50 with a 45% increased risk of developing early-onset colorectal adenoma polyps, a precursor to cancer.

Implications for SDG 2 (Zero Hunger) and SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production)

The UPF industry’s model of production and consumption conflicts with the principles of SDG 2 and SDG 12.

SDG 2: Zero Hunger

While UPFs may be inexpensive, their low nutritional value undermines SDG Target 2.2, which aims to end all forms of malnutrition. By displacing traditional, nutrient-dense diets, especially in developing nations, UPFs contribute to a new form of malnutrition characterized by high-calorie, low-nutrient consumption.

SDG 12: Responsible Consumption and Production

The production and marketing of UPFs represent an unsustainable pattern of consumption and production.

- Unsustainable Production: UPFs are derived from inexpensive industrial ingredients, which encourages production systems that are not aligned with sustainable agriculture or food security.

- Unsustainable Consumption: Aggressive marketing, particularly to vulnerable populations like children, drives overconsumption and displaces healthier, more sustainable dietary patterns.

- Barriers to Policy: The influence of the highly profitable UPF industry on policy-making is a primary barrier to effective government action, hindering progress toward responsible consumption frameworks.

Policy Recommendations and the Role of Global Partnerships (SDG 17)

Addressing the UPF challenge requires a coordinated global effort, reflecting the spirit of SDG 17 (Partnerships for the Goals). The Lancet series calls for sustained international action to counter the power of the UPF industry and implement effective public health policies.

Key Policy Actions Recommended:

- Implement measures to reduce the production, marketing, and consumption of UPFs.

- Develop programs to expand access to and affordability of fresh and minimally processed foods.

- Establish a strong global response to protect public health policy-making from industry lobbying and influence.

Recommended Dietary Patterns for Health and Sustainability

Promoting protective dietary patterns is essential for mitigating the health risks of UPFs and advancing public health goals. These patterns align with sustainable and healthy living principles.

Characteristics of Protective Diets:

- Emphasis on vegetables, whole fruits, whole grains, nuts, fish, and fermented dairy.

- Limitation of red and processed meats and added sugars.

- Absence or minimal inclusion of ultra-processed foods.

Individual Actions to Reduce UPF Intake:

- Replace processed snacks with whole foods like fruit, nuts, seeds, and plain yogurt.

- Prepare homemade versions of common UPFs, such as salad dressings, hummus, and granola.

- Opt for minimally processed proteins, such as roasted turkey, instead of processed deli meats.

1. Which SDGs are addressed or connected to the issues highlighted in the article?

The article on ultra-processed foods (UPFs) and their health implications directly addresses and connects to several Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The primary focus is on health, but it also touches upon nutrition, and responsible consumption patterns.

-

SDG 2: Zero Hunger

While not focused on hunger, the article connects to SDG 2 through its emphasis on nutrition and food quality. It highlights how UPFs are “displacing long-established diets centred on whole and minimally processed foods, resulting in a decline in diet quality” and causing “nutrient imbalances.” This directly relates to the goal of ending all forms of malnutrition.

-

SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being

This is the most prominent SDG in the article. The text is centered on the negative health impacts of UPFs, describing their rise as a “major new challenge for global public health.” It explicitly links high UPF intake to an increased risk of non-communicable diseases (NCDs), stating that evidence found “adverse health outcomes across nearly all organ systems,” including “inflammation, elevated blood glucose, cholesterol and triglyceride levels,” and an increased risk of “heart disease, stroke, Type 2 diabetes and certain cancers” like early-onset colorectal cancer.

-

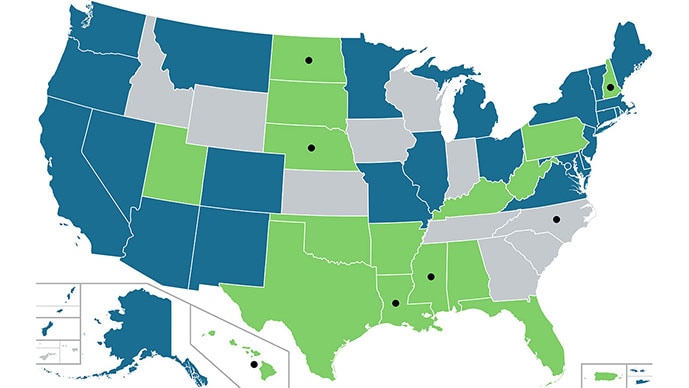

SDG 12: Responsible Consumption and Production

The article addresses this goal by discussing the consumption patterns of UPFs and the need for policy changes. It notes that UPFs “make up 46 per cent of calories consumed in Canada and about 55 per cent of calories consumed in the U.S. and the U.K.” and are “aggressively marketed (especially to children).” The call for a “co-ordinated and urgent effort to reduce the consumption of UPFs” and for “policy actions to reduce UPF production, marketing and consumption” aligns directly with the principles of responsible consumption.

2. What specific targets under those SDGs can be identified based on the article’s content?

Based on the issues discussed, several specific SDG targets can be identified:

-

Target 2.2: End all forms of malnutrition

The article directly supports this target by explaining how UPFs contribute to poor nutrition. It states that diets high in UPFs lead to “nutrient imbalances” and a “decline in diet quality.” The promotion of “healthier diets” centered on “vegetables, whole fruit, whole grains, nuts, fish and dairy” is presented as the solution to this form of malnutrition.

-

Target 3.4: Reduce by one-third premature mortality from non-communicable diseases (NCDs)

This target is central to the article’s argument. The text provides extensive evidence linking UPF consumption to the risk factors and development of NCDs. It mentions that a high intake of UPFs increases the risk of “multiple chronic diseases,” including “heart disease, stroke, Type 2 diabetes and certain cancers.” The study on colorectal polyps further substantiates this by showing a “45 per cent increased risk of developing early-onset colorectal adenoma polyps” in those with the highest UPF intake.

-

Target 12.8: Ensure that people everywhere have the relevant information and awareness for sustainable development and lifestyles

The article itself serves to increase awareness about the harms of UPFs. Furthermore, it discusses the need to counter the “aggressively marketed” nature of these products and address the “power of the hugely profitable UPF industry” to protect policymaking. The recommendations to reduce intake and make healthier choices, such as preparing food at home and choosing whole foods, are aimed at empowering consumers with information to adopt healthier, more sustainable lifestyles.

3. Are there any indicators mentioned or implied in the article that can be used to measure progress towards the identified targets?

Yes, the article mentions and implies several quantitative and qualitative indicators that can be used to measure progress.

-

Percentage of calories from UPFs in national diets

This is a direct, quantifiable indicator mentioned in the article. It states that “UPFs make up 46 per cent of calories consumed in Canada and about 55 per cent of calories consumed in the U.S. and the U.K.” Tracking this percentage over time would be a clear measure of progress in reducing UPF consumption.

-

Incidence and prevalence of non-communicable diseases and their risk factors

The article implies these indicators by linking UPFs to specific health outcomes. Progress could be measured by tracking rates of “early-onset colorectal cancer,” “Type 2 diabetes,” “heart disease,” and “stroke.” Additionally, monitoring biological markers mentioned in the article, such as levels of “blood glucose, cholesterol and triglyceride,” would serve as indicators of population health improvement.

-

Per capita consumption of UPFs

The study on colorectal polyps uses “servings a day” as a measure of intake, comparing those with the “highest UPF intake (10 servings a day)” to those with the “lowest intake (three servings per day).” This suggests that the average number of daily or weekly servings of UPFs consumed per person is a viable indicator for tracking consumption patterns.

-

Implementation of policies to reduce UPF consumption

The article calls for “policy actions to reduce UPF production, marketing and consumption.” An indicator of progress would be the number and scope of government policies implemented, such as marketing restrictions (especially to children), front-of-pack labeling, or taxes on unhealthy products, as well as measures to “expand access to fresh foods.”

4. Create a table with three columns titled ‘SDGs, Targets and Indicators” to present the findings from analyzing the article.

| SDGs | Targets | Indicators |

|---|---|---|

| SDG 2: Zero Hunger | Target 2.2: End all forms of malnutrition. |

|

| SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being | Target 3.4: Reduce by one-third premature mortality from non-communicable diseases (NCDs). |

|

| SDG 12: Responsible Consumption and Production | Target 12.8: Ensure that people everywhere have the relevant information and awareness for sustainable development and lifestyles. |

|

Source: theglobeandmail.com

What is Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0