Will NATO Counter the Brazenness of Turkey’s Blue Homeland Doctrine? – Middle East Forum

Report on the “Blue Homeland” Doctrine and its Implications for Sustainable Development Goals

A recent round of confidence-building talks between Turkish and Greek delegations on October 23, 2025, was described as “positive and constructive.” However, these diplomatic efforts are fundamentally undermined by Turkey’s “Blue Homeland” (Mavi Vatan) maritime doctrine. This report analyzes the doctrine’s impact on regional stability, international law, and the advancement of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 16 (Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions).

Impact on SDG 16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions

The “Blue Homeland” doctrine presents a direct challenge to the principles of SDG 16 by eroding international legal frameworks, weakening institutional cooperation, and fostering conditions for conflict rather than peace.

Erosion of International Law and Governance

Since 2006, Ankara’s doctrine has redefined maritime zones as non-negotiable national territory, creating a framework for “perpetual conflict” that contravenes the objectives of SDG 16. This is achieved through several actions:

- Rejection of UNCLOS: Turkey’s refusal to ratify the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) undermines the primary international legal framework for governing marine and maritime activities, weakening the “rule of law at the national and international levels” as called for in SDG 16.

- Unilateral Declarations: The doctrine justifies unilateral declarations of Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs), such as the 2019 Memorandum of Understanding with Libya. This agreement infringes upon the sovereign rights of Greece and Cyprus, violating international norms and destabilizing regional order.

- Disruption of Diplomacy: By framing maritime disputes as existential claims, the doctrine transforms areas of potential diplomatic negotiation into permanent conflict zones, hindering progress toward peaceful and inclusive societies.

Weakening of Multilateral Institutions

The doctrine’s implementation has weakened key international partnerships, most notably NATO. By pursuing expansionist claims against a fellow member, Greece, Turkey erodes the trust and cohesion essential for collective defense. This internal friction challenges the effectiveness and credibility of international institutions, which are a cornerstone of SDG 16.

Challenges to Sustainable Economic and Environmental Goals

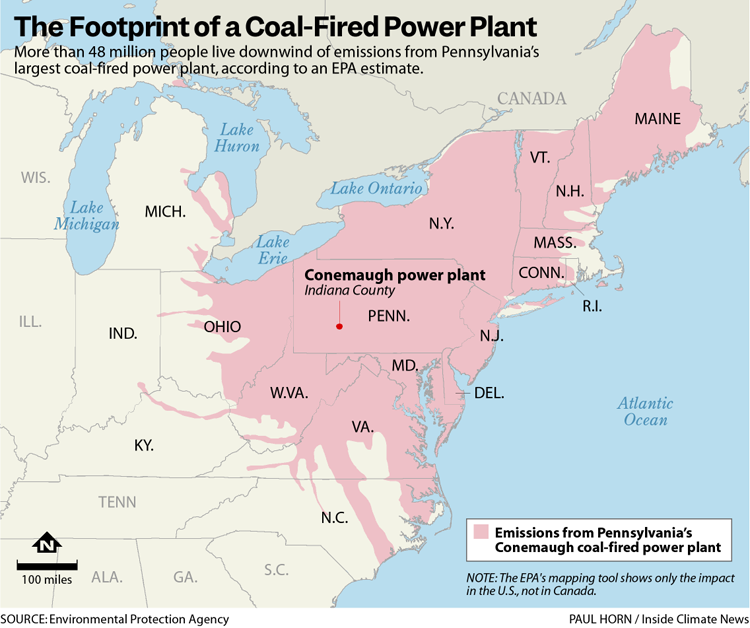

The regional instability created by the “Blue Homeland” doctrine has significant negative consequences for sustainable resource management and energy security, impacting SDG 14 (Life Below Water) and SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy).

Implications for SDG 14: Life Below Water

The contestation over vast maritime territories obstructs the cooperative governance necessary for the conservation and sustainable use of marine resources. The doctrine’s rejection of established legal frameworks creates uncertainty and impedes collaborative efforts to manage shared marine ecosystems, directly conflicting with the aims of SDG 14.

Implications for SDG 7: Affordable and Clean Energy

Ankara’s assertive posture threatens regional energy security and investment in sustainable energy infrastructure.

- Investment Risk: The aggressive maritime claims inject uncertainty into energy development projects, such as the EastMed gas corridor, which is intended to enhance Europe’s energy security and diversify supplies.

- Regional Instability: Repeated NAVTEX alerts and challenges to research vessels in contested waters create a volatile environment that discourages the long-term investment required to achieve the goals of SDG 7.

Long-Term Obstacles to Sustainable Development

The ideological entrenchment of the “Blue Homeland” doctrine poses long-term barriers to achieving SDG 4 (Quality Education) and SDG 17 (Partnerships for the Goals).

Undermining SDG 4: Education for Global Citizenship

The integration of the “Blue Homeland” doctrine into Turkey’s national school curriculum is a significant concern. By teaching students to view maritime disputes as national liberation struggles against “unjust claims,” this educational approach promotes a nationalist and revisionist worldview. This is contrary to the spirit of SDG 4, which aims to promote education for sustainable development, global citizenship, and an appreciation of cultural diversity and peace.

Failure of SDG 17: Partnerships for the Goals

The doctrine is fundamentally at odds with the collaborative spirit of SDG 17. It has led to the breakdown of regional partnerships and undermines initiatives aimed at fostering cooperation, such as the proposed revival of an Eastern Mediterranean Forum. Turkey’s rejection of established international law makes its participation in such a partnership unlikely, preventing the region from addressing shared challenges and achieving sustainable development through collective action.

Analysis of Sustainable Development Goals in the Article

1. Which SDGs are addressed or connected to the issues highlighted in the article?

-

SDG 16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions

- The article’s central theme is the lack of peace and stability in the Eastern Mediterranean due to maritime disputes between Turkey and Greece/Cyprus. It discusses the failure of diplomatic talks (“confidence-building measures”), challenges to international law, and actions that undermine regional stability and NATO cohesion, all of which are core concerns of SDG 16.

-

SDG 14: Life Below Water

- The conflict is rooted in disputes over the control and use of marine resources and maritime zones, including continental shelves and exclusive economic zones (EEZs). The article explicitly references the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) as the key international legal framework for ocean governance, which Turkey rejects. This directly relates to the sustainable use and governance of marine resources.

-

SDG 7: Affordable and Clean Energy

- The article highlights how Turkey’s “aggressive maritime posture threatens both regional order and Western energy security.” It specifically mentions that the disputes inject “uncertainty into energy investment and development such as the EastMed corridor” and affect “gas exploration and pipelines.” This connects the regional conflict to the goal of ensuring access to reliable and modern energy by disrupting international cooperation and investment in energy infrastructure.

2. What specific targets under those SDGs can be identified based on the article’s content?

-

Under SDG 16 (Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions):

- Target 16.3: Promote the rule of law at the national and international levels and ensure equal access to justice for all. The article directly addresses this target by detailing Turkey’s rejection of “the framework of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea” and its challenge to “international norms.” The conflict arises from a refusal to adhere to established international law in favor of a unilateral interpretation.

- Target 16.6: Develop effective, accountable and transparent institutions at all levels. The article mentions “confidence-building measures talks” between Turkey and Greece, but notes that “strategic trust between the two NATO allies remains low,” indicating these institutional mechanisms are not fully effective. The proposal to revive an “Eastern Mediterranean Forum” is another attempt to build a regional institution for dialogue and cooperation.

-

Under SDG 14 (Life Below Water):

- Target 14.c: Enhance the conservation and sustainable use of oceans and their resources by implementing international law as reflected in the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. This target is central to the article’s conflict. The disputes over EEZs, continental shelves, and maritime boundaries are a direct result of Turkey’s refusal to ratify and implement UNCLOS, the very instrument this target promotes as the basis for ocean governance.

-

Under SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy):

- Target 7.a: By 2030, enhance international cooperation to facilitate access to clean energy research and technology… and promote investment in energy infrastructure and clean energy technology. The article shows how the regional instability caused by Turkey’s actions is a barrier to this target. The conflict creates “uncertainty into energy investment and development such as the EastMed corridor,” directly hindering the international cooperation necessary for major energy infrastructure projects.

3. Are there any indicators mentioned or implied in the article that can be used to measure progress towards the identified targets?

-

For SDG 16 (Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions):

- Indicator (Implied for Target 16.3): The ratification and implementation of international treaties. The article explicitly states that Turkey “refuses to ratify” UNCLOS. A key measure of progress would be Turkey’s acceptance and implementation of this convention.

- Indicator (Implied for Target 16.6): The frequency and outcome of bilateral and regional dialogues. The article mentions “positive and constructive” talks, but also low trust. The establishment and successful operation of the proposed “Eastern Mediterranean Forum” would be a positive indicator of institutional effectiveness.

- Indicator (Implied): The number of unilateral actions or provocations versus negotiated settlements. The article cites Turkey’s issuance of “six [NAVTEX alerts] between 2024 and 2025 alone” and the “unilateral maritime zones” as negative indicators. A reduction in such actions in favor of diplomatic agreements would signify progress.

-

For SDG 14 (Life Below Water):

- Indicator (Directly related to Target 14.c): The degree of implementation of UNCLOS. The official indicator 14.c.1 measures countries’ progress in implementing ocean-related instruments based on UNCLOS. The article’s focus on Turkey’s non-ratification of UNCLOS provides a direct, though negative, data point for this indicator.

-

For SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy):

- Indicator (Implied for Target 7.a): The level of investment in and development of cross-border energy infrastructure. The article points to the “uncertainty into energy investment and development such as the EastMed corridor.” The progress or failure of such projects serves as a tangible indicator of the stability and international cooperation required to meet this target.

4. Table of SDGs, Targets, and Indicators

| SDGs | Targets | Indicators Identified in the Article |

|---|---|---|

| SDG 16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions |

Target 16.3: Promote the rule of law at the national and international levels.

Target 16.6: Develop effective, accountable and transparent institutions at all levels. |

– Ratification status of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) by Turkey. – Number of unilateral maritime boundary declarations and military/research vessel alerts (e.g., NAVTEX alerts). – Existence and effectiveness of regional dialogue platforms (e.g., “confidence-building measures talks,” proposed “Eastern Mediterranean Forum”). |

| SDG 14: Life Below Water | Target 14.c: Enhance the conservation and sustainable use of oceans and their resources by implementing international law as reflected in the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. |

– Adherence to the principles and framework of UNCLOS for managing maritime zones (EEZs, continental shelves). – Number of maritime agreements that are in violation of UNCLOS (e.g., the 2019 Turkey-Libya memorandum). |

| SDG 7: Affordable and Clean Energy | Target 7.a: Enhance international cooperation… and promote investment in energy infrastructure. |

– Level of investment and progress in regional energy projects (e.g., the EastMed corridor). – Stability and security for gas exploration and pipeline development in the Eastern Mediterranean. |

Source: meforum.org

What is Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0